Whether a first or second focal plane scope is best depends on your intended purposes.

Tactical and competitive shooting sports are crossing over into the hunting world more than ever, sparking frequent debates about whether first or second focal plane scopes—or more accurately, the reticles inside the scopes—are better.

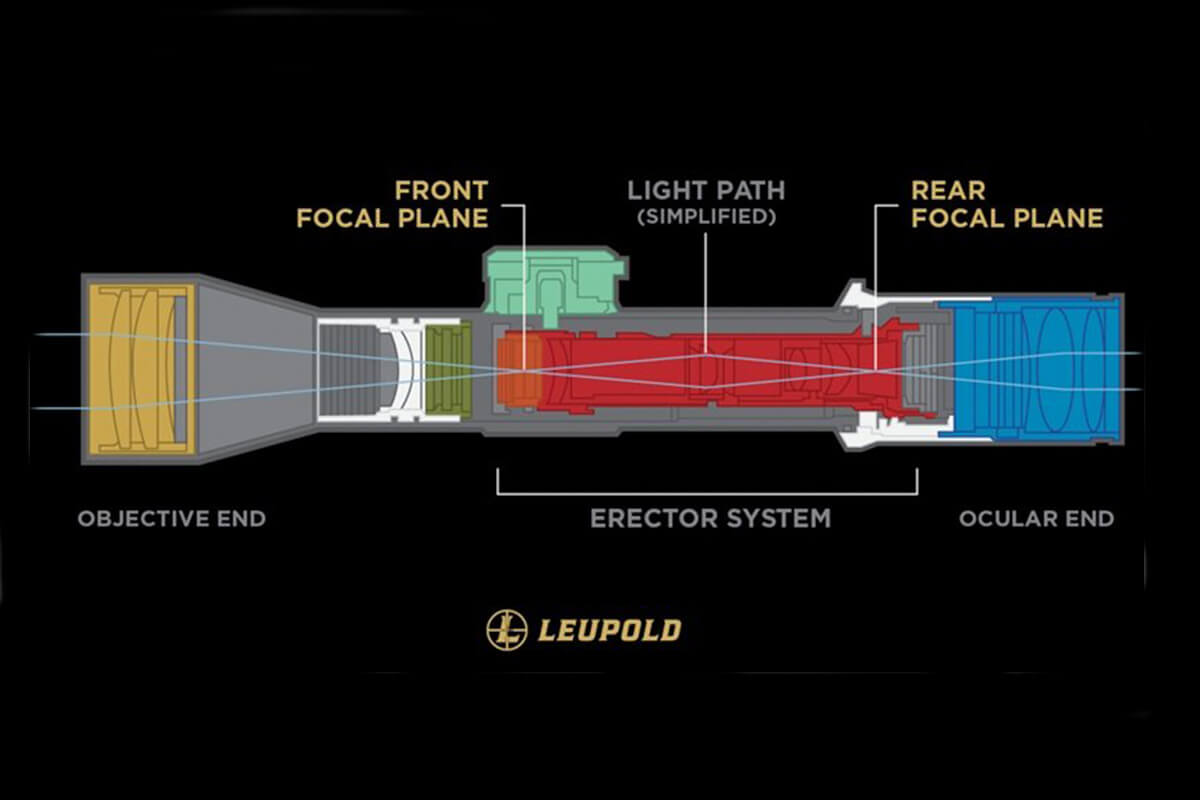

Also known as front and rear focal plane, this refers to the position of the lens etched with the reticle, in relation to the zoom mechanism.

If the reticle-etched lens is in front of the zoom mechanism, it’s called a first, or front, focal plane scope. The reticle is superimposed over the image in the scope on the same plane, so as you zoom in or out, the reticle larger or smaller, maintaining the same size in relation to your target.

If the lens etched with the reticle is behind the zoom mechanism, it’s called a second, or rear, focal plane scope. In this design, the reticle stays the same apparent size inside the scope all the time. As you zoom in or out, the image seen inside the optic gets larger or smaller but the reticle does not.

There are significant advantages and disadvantages of each type. Proponents of first focal plane designs are vociferous in proclaiming the virtues of their favorite. Users of second focal plane scopes tend, quite candidly, to be less educated in optic technicana, and unfortunately often just listen without debating.

Here’s the short answer as to which is actually best: It depends entirely on the intended purpose of the scope. If you’re a military sniper, or a “tactard” plinker, or a PRS competitive shooter, front focal plane scopes are best. If you’re a hunter, second focal plan scopes are usually best.

Here’s why.

Front Focal Plane Scopes

Military and tactical-type shooters often rely on hash reticle hash marks to compensate for wind drift, and for on-the-fly minor variances in bullet impact above or below expected point of impact. In a first focal plane scope, the hash marks on the reticle crosswire are the same predictable value no matter what magnification the scope is set on. Whether you are zoomed way in on a very small target, or zoomed way out so as to maximize our field of view when engaging multiple or moving targets, .2-MIL hash marks are always .2 MILs. If you need to hold for 6 MILs of wind drift, just use the appropriate hash mark and squeeze the trigger.

That’s it for the advantage of first focal plane reticles, folks. It’s a very simple, yet critical characteristic. The disadvantages are more nuanced, and as a result are harder for many shooters to grasp—until experienced for themselves.

Here’s the down side to front focal plane reticles: When the scope is zoomed way in, the reticle grows to the point where it becomes outlandishly thick. It can easily become so thick it obscures your target, making precise aiming difficult.

To compensate, most optic companies make front focal plane reticle crosswires really thin near the center. Unfortunately, that makes it so when you zoom way out, the reticle becomes super thin and can nearly vanish.

Most tactical and competitive shooters prefer to shoot with their scope on 10x or more, so it’s not really a problem for them. However, if you use a first focal plane reticle while hunting, that vanishing reticle on low power can be debilitating.

This is particularly true in low light conditions, and when the game animal is against a brushy background. To gather enough light to see the animal, you’ve got to zoom the scope all the way out. (Scopes gather and transfer light most effectively on low power.) Trouble is, with the reticle now spiderweb-thin, it vanishes in the twilight, especially if there’s brush around the animal.

Where legal, illuminated reticles can help overcome the vanishing-reticle syndrome. However, many states do not allow illuminated reticles for hunting. Plus, most illuminated reticles are too illuminated, meaning the entire thing or at least the major percentage of the reticle glows. A tiny pinpoint of light in the center of the reticle is wonderful; a Christmas tree worth of vibrant glowing reticle is distracting and can make it difficult to see through and find your quarry in the fading light.

Second Focal Plane Reticles

Second focal plane scopes are the world standard for hunters, and for good reason; the reticle stays the same size whether zoomed in or out. You can crank up to top magnification and see the wings on a fly at 100 yards; the reticle doesn’t become grossly fat. You can zoom all the way out for low-light hunting, and the reticle stays perfectly visible rather than thinning to obscurity.

I’m gonna take a cheap-shot at pseudo-tactical shooters that proclaim second focal plane reticles are outdated and near useless: Most shooters making such claims have little real-world experience on live targets, in wild environments; on stealthy game that moves only when the shadows grow long. Be a little more open-minded, and listen to the guys that consistently stalk and kill the wariest wild game, from torrid deserts to frigid timberline, in all kinds of weather and light conditions. You’ll learn something about what works best for hunting.

So, if second focal plane scopes are so good, what’s the down side? It applies to technical extended-range shooters that calculate wind holds, or hold over a distant target using reticle hash marks to compensate for bullet drop rather than dialing up.

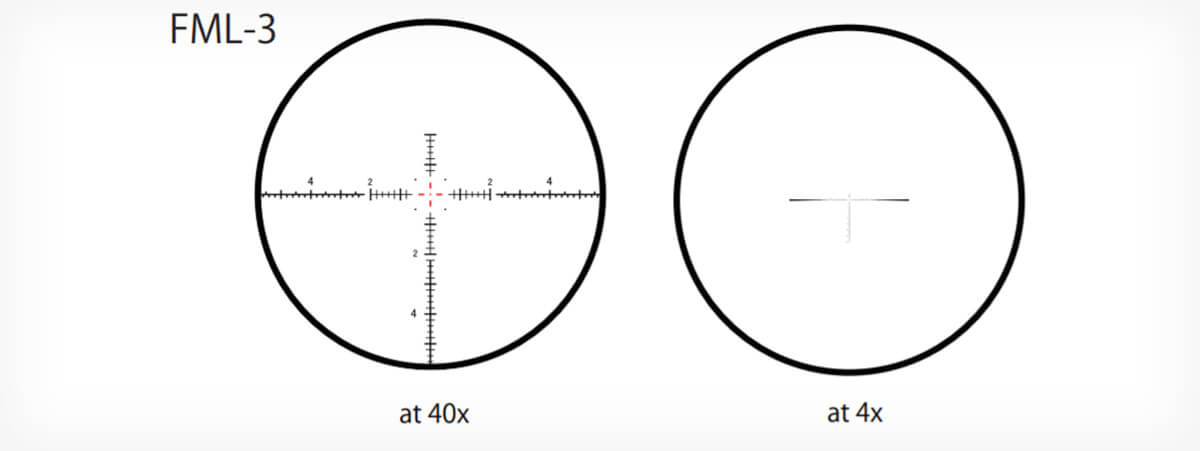

If a second-focal-plane reticle incorporates hash marks, it has a significant Achilles Heel: They are only good at one magnification setting. For example, my favorite hunting reticle is Leupold’s WindPlex. It’s got one-MOA hash marks on the horizontal crosswire to help shooters accurately compensate for calculated wind drift. However, those hash marks span exactly one MOA only on max power. For example, a 3-18x 44mm Leupold VX-6HD must be zoomed all the way to 18x for the hashes to have exactly a one-MOA span.

I don’t like to shoot at game animals on max power. It’s hard to find your quarry when you’re zoomed all the way in. You almost never spot your own impacts, because the field of view is small and recoil causes your rifle to jump. It’s hard to find the animal for a fast follow-up shot. In Mexico, I once failed to get a critical second shot into an animal because my scope was on 18x. The big coues buck trotted off when the bullet hit, and I couldn’t get back on him.

Thankfully, there’s a shooter’s hack that helps: Set your scope on half power, and double the value of the hash marks. Set on 9x (halfway down from 18x), my Leupold reticle’s hash marks span two MOA.

As a result, unless inside 300 yards, I rarely use anything but half-magnification when hunting with second focal plane reticles equipped with hash marks.

There you have it: the primary pros and cons of first versus second focal plane scopes. Maybe, like me, you own and use both, and pick up whichever is appropriate for the task at hand. Perhaps you use just one rifle for everything from backcountry hunting to long-range cross-country NRL Hunter matches. In the end, only you can decide which is best for your purposes.