Look at the vital zone outlined on the average 3D deer target, and you’ll see an area that reinforces what most of us have been taught about aiming at a broadside deer: Hold behind the crease of the shoulder, slightly below centerline of the chest. Most of the time, if you hit that, it does mean a dead deer. But there’s a better place to aim.

Keep the shot height the same, just below center. But pull the sight pin forward just a little, settling it about an inch ahead of the shoulder crease. Assuming the front leg is vertical, you should be right in line with it. Bury your arrow there, and that deer won’t make it 100 yards. Most times, it won’t make it 50.

Plenty of rifle hunters aim at that spot as a practice, but generations of bowhunters have been taught to avoid the shoulder at all costs, for fear that heavy bone will stop an arrow before it penetrates deep enough to hit vitals. But that’s just a fallacy. If you do hit heavy bone in the shoulder area on a broadside deer, you’re several inches off the mark anyway, either too high or too far forward. You’ll probably lose that deer, but lack of penetration is not to blame.

(Don’t Miss: 15 Tips for One-Shot Kills)

I’ve killed right around 100 whitetails with a bow and followed at least that many more tracks for others. In recent years, many of those tracks have been with a blood dog. I can’t say that I’ve ever seen a deer escape from a shoulder hit due to lack of penetration. But I have seen several deer hit perfectly behind the shoulder that were only recovered after a long, difficult blood trail — and a couple more that were lost altogether.

Kip Adams, the Quality Deer Management Association’s director of conservation, is a shoulder-shooting convert. I’ve totally changed where I aim at deer now, from where I was taught to aim at them, he says. Like most hunters, I was always taught to aim right behind the shoulder. But that’s just not the best place. These days, I teach my kids, and all new hunters in our camps, to follow that front leg up.

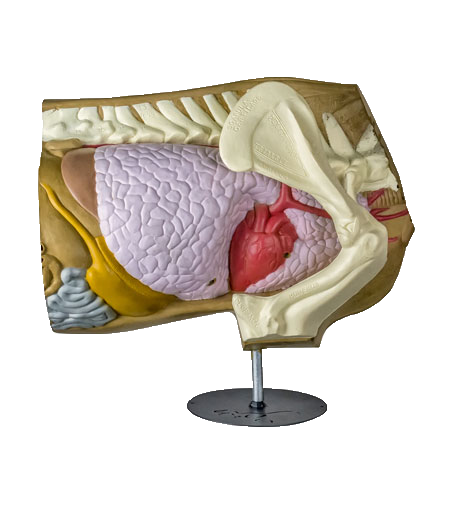

Proof’s in the Anatomy Lesson

Many hunters don’t understand the layout of a deer’s innards quite as well as they think they do. All the time, in our Deer Steward courses, I ask people to point to the heart — and many don’t know where it actually is because the only time they’ve seen a deer’s heart is while the animal was being field-dressed, Adams says.

But the heart and all of the largest, busiest blood vessels that go with it, plus the trachea and front third of the lungs, rests between the front quarters of a deer. Most bowhunters know a quartering-away shot is lethal within seconds, and the reason is because it passes through this frontal area. But many bowhunters also believe that a quartering-away shot is the only way to that frontal area because it allows you to slip behind the shoulder.

The heart and all of the largest, busiest blood vessels that go with it, plus the trachea and front third of the lungs, rests between the front quarters of a deer.

But you don’t have to go behind the shoulder. Just go through it. Contrary to popular belief, from a broadside angle, those vitals are not at all shielded by heavy bone. Instead, a deer’s shoulder bones are shaped something like a boomerang, held vertically. Envision the point of the boomerang as the edge of the brisket, pointed toward the deer’s nose. The scapula, then, is the top half, and the humerus is the bottom. Behind and between those bones, there’s nothing covering the ribs and vitals but muscle. It’s thick muscle, but no match against a modern compound bow (especially on whitetail-sized critters).

For that matter, the shoulder bones themselves aren’t that difficult to break on a deer, either. Just the other day, I shot a quartering-away doe and shattered the humerus on the off side. She died within 15 yards. My setup is a 60-pound, 28-inch Elite Kure, with a 475-grain finished arrow, including the 125-grain Wasp HV broadhead up front.

Hitting that bone on the exit doesn’t matter. Sure, it keeps your arrow from passing through, and will probably break it into three pieces. But if the deer’s dead within sight, who cares?

(Don’t Miss: How to Hunt Big Buck Bedding Areas)

Really, the only time you would purposely aim near those bones on the entry side is with a quartering-to shot. This is the most controversial shot angle in all of bowhunting, but it’s devastating if done properly. Hit the crease of the neck, ahead of the shoulder, on a quartering-to deer, and you have the shortest path possible to the heart. I’ve killed a dozen or so animals with this shot, including a couple of my best bucks, and have never lost one. Is it a smaller target? Yes, about the size of a softball, and so it’s a shot that I only take up close. But give me a 20-yard quartering-to opportunity versus a 40-yard broadside one, and I’ll personally take the 20-yarder every time.

The Problem Behind the Crease

You hear it all the time back at camp, when guys are wallowing in misery over the one that got away: I know I hit that buck good. There was good blood at first. Then it just quit, and I don’t know where he went.

The assumption is usually that the buck wasn’t hit as well as the hunter thought. But time spent with tracking dogs has allowed me to analyze shot placement on some deer that I know would’ve otherwise been lost. Very often, I’ve learned, the buck is hit where the hunter was aiming, right behind the shoulder. But the exit is back. What frequently seems to happen is those broadside deer are actually quartering slightly to the hunter at the shot, and the hunter doesn’t compensate for that. This is especially true when bowhunters at full draw give the old meh to stop a moving deer — because the deer twists slightly to look toward the source of the sound. By that point, though, the hunter has already picked a spot behind the shoulder and doesn’t notice or adjust for the slight angle. Sometimes that arrow catches the back edge of both lungs. Sometimes it hits one lung and the liver. Both wounds are fatal, but not always quickly. The hunter proceeds to the recovery too quickly … and you know the rest.

My wife’s buck from this past September is an example of how badly a behind-the-shoulder shot can go. She hit the deer with a crossbow and a hybrid-mechanical broadhead at 21 yards. She was steady, and the buck was broadside, best as she could tell. She snuck up and got her arrow after the hit, and it was soaked in bright red blood. We waited two hours, thinking we were just being extra-cautious. The blood trail was easy, with plenty of good bubbles. But 75 yards in, we jumped the buck. We immediately turned around and went back to camp.

We went back at daybreak the next day. The blood virtually stopped at the bed. With the help of a buddy and my tracking dog, we were able to extend the trail by a couple hundred yards, but then we lost it again. Finally, at around 1 p.m., buzzards over my neighbor’s field led me to the buck, 711 yards away according to my GPS. You can see the shot in the side-by-side photos above. Compare that with the average 3D target. The entry is a perfect 10-ring, and the exit is in the rear portion of the 8-ring. Michelle filled her buck tag — but tragically without any venison to show for it.

There are now countless resources for learning a deer’s anatomy. Many of those resources have borrowed an illustration that we posted on Realtree.com years ago, because that illustration accurately shows where the vitals truly sit within a whitetail’s chest, shoulder bones included. (Shoutout to my pal Ryan Kirby, who drew that original picture.)

Keep practicing on your 3D deer target, but do it with a grain of salt, if you’ve got an old-school target. Many bowhunters still learn about shot placement on 3D targets — and unfortunately, a bunch of those targets still have the wrong vital areas on them, Adams explains.

Get a target that’s anatomically correct, study up a little more, and then trust what you’ve learned the next time you draw on a deer and settle your pin just above that front leg. When that deer crashes within sight, you’ll be thankful for the extra homework.

(Check Out: 50 Bowhunting Tips to Read on Stand)