Sighting in or “zeroing” a rifle is the art of aligning iron or telescopic sights with the barrel, thus allowing the shooter to place bullets predictably at a given distance. In this article, we will focus on telescopic sights or “scopes” because they offer significant advantages over open sights, especially at longer distances.

Scopes have evolved with greater clarity and magnification to match the increasing power and precision of rifles and ammunition. Two systems for aligning scopes have developed independently. Each has a distinctly different origin and approach. The Minute of Angle (MOA) method is an ancient base-60 scheme conceived for astronomy. The Milliradian method is a base-10 scheme developed for artillery in the late nineteenth century. Nonetheless, both are equally effective, using segments of arc to express a certain amount of change in trajectory at a set distance.

MOA — Minute of Angle

Brief

One minute of angle, also known as an arcminute, is equal to a deviation of approximately 1 inch at 100 yards, 2.00 inches at 200 yards and 3.00 inches at 300 yards. One increment of adjustment on many MOA scopes moves the reticle alignment 0.25 (1/4″) of an arcminute or 0.25 inches at 100 yards, 0.50 inch at 200 yards and 0.75 of an inch at 300 yards. These measurements apply to both windage and elevation and are accomplished by rotating a turret adjuster on the scope. Some scopes move reticle alignment in .0125 (1/8″) increments, but many shooters consider this too narrow to be useful, especially at great distances.

Let us consider some examples. If you had a bullet drop of 1.50 inches at 200 yards and wanted to zero your rifle at this distance, you would need to adjust the elevation turret of your scope up by 3 increments or .75 of an arcminute because a minute of arc equals 2 inches at 200 yards. Using these convenient figures, we can generate the following results in Table 1 showing approximate arcminute deviations and the value of one increment at various ranges.

Arcminute DeviationsIncremental Scope Adjustments of 0.25 100 yards = 1.0 inch100 yards = 0.25 inch 200 yards = 2.0 inch200 yards = 0.50 inch 300 yards = 3.0 inch300 yards = 0.75 inch 400 yards = 4.0 inch400 yards = 1.00 inch 500 yards = 5.0 inch500 yards = 1.25 inch 600 yards = 6.0 inch600 yards = 1.50 inch 700 yards = 7.0 inch700 yards = 1.75 inch 800 yards = 8.0 inch800 yards = 2.00 inch 900 yards = 9.0 inch900 yards = 2.25 inch 1000 yards = 10.0 inch1000 yards = 2.50 inch

In order to compensate for a windage error of 2.50 inches to the right at 500 yards, you would need to adjust the windage turret toward the left by 2 increments or 0.50 arcminutes because a minute of arc equals 5.00 inches at 500 yards.

In Depth

The MOA system was handed down from the Sumerians in the 3rd millennium BC. The modern practice of dividing a circle into 360 degrees began with the Sumerians. The Babylonians further refined this measurement by dividing each degree into 60 minutes of arc. Since an arcminute is 1/60th of a degree, there are 21,600 (60 * 360) arcminutes in a full circle. Being a standalone system that is somewhat arbitrary, MOA feels akin to Imperial units, even though it is not part of that system and postdates it by more than two millennia.

True MOA

Shooting purists acknowledge a difference between commonly understood MOA and “true” MOA, which adheres strictly to the underlying mathematics. This meticulous attitude is necessary when acquiring targets that are several hundred yards away because the minor variations of rounded numbers are magnified by distance. In June of 2017, a Canadian Special Forces sniper downed an Islamic State militant from just over 2 miles away. The bullet took 10 seconds to reach its target. Shooting at this distance and accounting for wind, angle of trajectory, light aberration, and even the Earth’s curvature leaves no margin for error. More practically speaking, striking a mule deer from 400 yards, down a powerline slash in Western Montana requires you to be “on your game.”

Calculating the exact deviation of one MOA is a problem of geometry. The circumference of our circle is determined by the radius or distance from the shooter to target. At 100 yards, using the formula of 2 Ï r, we find that 2 * 3.14 * 100 = 628 yards. As there are 36 inches to a yard, the circumference in inches is 22,608. Now, all that remains is to divide by the number of MOA’s in a circle (21,600) and the quotient is 1.047. This is the actual deviation of one MOA at 100 yards.

Using this precise figure, we can generate the following table of MOA deviations, yielding greater accuracy. Note that the variance from rounded numbers is nearly half an inch at 1000 yards.

TRUE Arcminute DeviationsTRUE Incremental Scope Adjustments of 0.25″ 100 yards = 1.047 inch100 yards = 0.2617 inch 200 yards = 2.094 inch200 yards = 0.5235 inch 300 yards = 3.141 inch300 yards = 0.7852 inch 400 yards = 4.188 inch400 yards = 1.0470 inch 500 yards = 5.236 inch500 yards = 1.3088 inch 600 yards = 6.282 inch600 yards = 1.5705 inch 700 yards = 7.329inch700 yards = 1.8323 inch 800 yards = 8.376 inch800 yards = 2.0940 inch 900 yards = 9.423 inch900 yards = 2.3558 inch 1000 yards = 10.47 inch1000 yards = 2.6175 inch

Let us consider a few real-world examples using these more acute numbers. The bullet drop of a Norma 150 grain, 7mm Magnum bullet is 21 inches at 400 yards. Compensating for this drop would require an adjustment of 20 increments of one-quarter MOA for a total of 5 MOA because one minute of arc equals 4.188 inches at that distance.

Suppose you are shooting a 180 Grain Remington Express in 30.06, from a rifle zeroed at 200 yards. The range of your target is 400 yards, producing a bullet drop of 23 inches. You are shooting to the north and there is a 10 mph wind from the east. In order to compensate for the drop, you would need to adjust the elevation turret up by 22 increments. Wind drift would be about 12 inches, based on the known ballistic coefficient for that bullet, requiring a windage turret adjustment of 11 increments to the right for a total change of nearly 3 MOA.

MRAD — Milliradian

Brief

A radian or “rad” is the standard unit of angular measure used in many areas of mathematics. A Radian is slightly under 57.3 degrees. A milliradian or “mil” is one thousandth of a radian. There are approximately 6283 mils in a full circle.

Just as arcminutes have a predetermined value at various ranges, so do milliradians. These are typically expressed in meters (metric system) rather than yards, for reasons we will examine shortly. Milliradian scopes usually adjust in one-tenth (.10) increments because one full mil makes a sizable difference, even at 100 meters.

The deflection of .10 mils is understood to be 1 cm at 100 meters, 2 cm at 200 meters and 3 cm at 300 meters. The fact that the milliradian system works out to whole numbers makes calculating trajectory and adjusting for windage and elevation very straightforward. If, for example, you have to account for a bullet drop of 33 cm at 300 meters, you would need to adjust the elevation turret up by 11 increments. Compensating for wind drift of 3 cm to the right at 100 meters would require an adjustment of 3 increments to the left.

In Depth

The milliradian system is an International System of Units (SI) derived method of angular measurement. All SI units are based on science. A radian is mathematically defined as an arc-length equal to the radius of its circle. Therefore, the milliradian or “mil” is equal to 1/1000th of the radius. It was first proposed by Swiss engineer, Charles-Marc Dapples, in the mid-nineteenth century and came into prominent use for French artillery during World War I.

The established deflection of .10 mils is .9999 centimeters (cm) at 100 meters, or for all practical purposes, 1 cm. A difference of one ten-thousandth (.0001) of a centimeter is simply too small to be worthy of distinction. Even at 1000 meters, the margin of error would be a mere 1000th of a centimeter (99.99 vs 100 cm). Therefore, at 200 meters a tenth of a mil is considered 2 cm and at 300 meters it is 3 cm. We can extrapolate from these numbers to produce the table below.

Mil DeviationsIncremental Scope Adjustments of 0.10 Mils 100 meters = 10 cm100 meters = 1.0 cm 200 meters = 20 cm200 meters = 2.0 cm 300 meters = 30 cm300 meters = 3.0 cm 400 meters = 40 cm400 meters = 4.0 cm 500 meters = 50 cm500 meters = 5.0 cm 600 meters = 60 cm600 meters = 6.0 cm 700 meters = 70 cm700 meters = 7.0 cm 800 meters = 80 cm800 meters = 8.0 cm 900 meters = 90 cm900 meters = 9.0 cm 1000 meters = 100 cm1000 meters = 10.0 cm

Table 1. Mil and 0.10 mil deviations at ranges from 100 to 1000 meters.

Now for some real-world examples. Suppose you are firing a 140 grain 7.62 mm bullet, from a weapon zeroed at 100 meters, at a target that is 300 meters down range. The bullet drop would be 42 centimeters. You would need to adjust the elevation turret up by 14 increments, since each tenth of a mil would equal 3 cm at that distance. Next you are sighting with a Hornady 140 grain 6.5 mm Creedmoor at 500 meters and it is hitting 5 cm to the right. You would need to adjust your windage turret 1 increment to the left, since each tenth of a mil equals 5 cm at 500 meters.

MOA vs. MRAD

Each system has advantages. Here are a few considerations:

MOA Advantages

- 1/4 MOA adjustments (2.1675″@1000 yards) are nearly twice as refined as 1/10 mil adjustments (3.93701″@1000 yards).

- MOA is more familiar if you live in a country that uses Imperial measurements.

- Most ballistic tables are in feet and yards.

MRAD Advantages

- Base 10 metric values calculate more easily.

- More high-end equipment is MRAD & more pros use it.

- The US Military and many other forces around the globe have standardized on MRAD, influencing production & use.

Beyond this, both systems are equally effective. The question is not which is superior but which is better for you. Generally, if you are more comfortable with the Imperial system of measurements (inches, feet, yards), than the MOA system will feel more familiar. If you favor the Metric system (centimeters, meters), then MRAD may quickly seem like an old friend. Whichever system you choose, you will probably require at least a passing understanding of the other because they overlap in some important ways.

- Many scopes mix the two systems, having a mil dot reticle but turret adjustments in one-quarter minutes of arc.

- Although math is simpler in the base-10 metric system, most ballistic charts are in imperial measurements, requiring conversion from feet and yards to centimeters and meters.

Subtension

Subtension refers to the length of arc at a set distance, described by two radii that are separated by a certain angle. Subtension is a relative term and subject to the system of measurement used. In the context of MOA, for example, it would be evaluated in arcminutes, yards and inches.

So, imagine that you are looking at an object at a distance of 100 yards and the width of your view is two minutes of arc. The subtension would be 2.094 inches. We would say that the angle of two MOA is subtended by an arc distance of 2.094 inches at 100 yards. Not surprisingly, an arc of one milliradian at 300 meters is subtended by a circumferential distance of 30 centimeters. While these terms may seem initially confusing, speaking correctly about such concepts is the beginning of thinking correctly about them and ultimately leads to the power of using them properly.

Subtension becomes valuable when using a scope reticle to calculate the size or distance of an object, as well as the accuracy of shot placement. Next we will examine the application of subtension for this purpose in greater detail.

Triangulation

The process of determining a distance or location by using the knowledge of two other points is known as triangulation. It applies equally to MOA and MRAD and the principles are the same. We will use the latter for illustration because the math is more transparent.

Mil scopes are those with turrets that adjust in increments of mils and also have crosshairs that are segmented into mils (the space between one dot center and another). Milliradian measurements can be used to zero your scope at a given range, assess your shot groupings, determine the size of a target or calculate the range.

You can determine the accuracy of your shots from a known distance by using the reticle as a ruler. If your rangefinder reads 1000 meters and your bullet lands 1 mil-space to the right, then you are off by about 100 cm or 1 meter (subtension). The size of groupings can be found by the same method. If your shots appear to be separated by no more than a mil at 1000 meters, then they are all within 1 meter of each other. Similarly, a target image that appears to be 1 mil high at a range of 1000 meters is actually about 1 meter tall. You can also calculate the range in meters if the target size is known. Just divide the size of your target in millimeters by the number of mils it spans on the reticle. Let us say that you are firing upon a paper sheet that is 1 meter square (1000 mm) and it spans 1 mil on the reticle. Dividing 1000 by 1 yields a quotient of 1000. The range is 1000 meters.

Magnification

Magnification is an important consideration when triangulating. If the reticle is installed on the first focal plane of the scope, it will alter by magnification exactly as the view and remain constant with respect to target image. Such a reticle may be used at every level of amplification. However, if the reticle is installed on the second focal plane, it will remain fixed in size as the view changes, varying the ratio between mils and image. In this case, triangulation may only be performed at one designated magnification; usually at the highest point or halfway.

Calculations and Conversions

Here are some formulae that make manipulating both Imperial and Metric measurements more accessible:

Formulae for Milliradian Based Reticles

Distance to Target (Yards): D=H/IÃ1000Where D is target distance (yards), H is target height (yards), I is image size (mils), and the quotient is multiplied by a factor of 1000.

Distance to Target (Yards): D=H/IÃ27.77Where D is target distance (yards), H is target height (inches), I is image size (mils), and the quotient is multiplied by a factor of 27.77.

Distance to Target (Meters): D=H/IÃ25.40Where D is target distance (meters), H is target height (inches), I is image size (mils), and the quotient is multiplied by a factor of 25.40.

Distance to Target (Meters): D=H/IÃ1000Where D is target distance (meters), H is target height (meters), I is image size (mils), and the quotient is multiplied by a factor of 1000.

Distance to Target (Meters): D=H/IÃ10Where D is target distance (meters), H is target height (centimeters), I is image size (mils), and the quotient is multiplied by a factor of 10.

Formulae for Arcminute Based Reticles

Distance to Target (Yards): D=H/IÃ95.5Where D is target distance (yards), H is target height (inches), I is image size (MOA), and the quotient is multiplied by a factor of 95.5.

Distance to Target (Meters): D=H/IÃ87.30Where D is target distance (meters), H is target height (inches), I is image size (MOA), and the quotient is multiplied by a factor of 87.30.

Distance to Target (Meters): D=H/IÃ3438Where D is target distance (meters), H is target height (meters), I is image size (MOA), and the quotient is multiplied by a factor of 3438.

Distance to Target (Meters): D=H/IÃ34.38Where D is target distance (meters), H is target height (centimeters), I is image size (MOA), and the quotient is multiplied by a factor of 34.38.

Application

So far, our examination of this subject has been mostly theoretical and the calculations approximate. In the field, there are many considerations. You need to watch a few hundred bullets of your favorite caliber go down range from your preferred setup before you can make calls that result in consistent hits at distances well over 100 yards. Still, shooting accurately begins with assumptions based on theory. Then it must be refined by hard core experience. There is no shortcut to shooting accurately in such highly variable situations as big-game hunting or battle. You just have to live there for a bit. Keeping that in mind, here is some useful advice.

Scope and Mount

Standardize on ONE System

Choose a scope that has reticle segments and turret increments in the same system and mount similar scopes on ALL of your weapons. Use either an MOA reticle and 0.25″ MOA adjustments or a mil-dot reticle and 0.1 MRAD adjustments. Splitting between the two will add an additional layer of complexity to your calculations when zeroing, ranging, etc.

Mount and Align Your Scope

Mount your scope as low as possible, using established procedures. This process has many variables and is beyond the breadth of this article. If you are unsure, have a gunsmith mount it for you.

Set Eye Relief

Check and adjust the eye relief. If the focal distance of the scope is not adjusted correctly, it will strike your forehead when the weapon recoils and cut a neat ring into your skin.

Align the Reticle

Make sure that the cross hairs are exactly in line with the vertical and horizontal planes. If they are not, all of your adjustments will be off. This condition is referred to as reticle cant.

Sighting In

Get Set & Level

Get yourself and the weapon set and solidly supported in a comfortable position, on a level plane. All testing and adjustments depend upon your steadiness and precision in handling the weapon.

Zero Point

Decide on a point at which you want the rifle to be dead-on. This should be chosen based on the bullet trajectory and your anticipated shooting range. Bullets travel in an arc, at first rising slightly with energy and then falling as they succumb to gravity. Consequently, your Point-of-Aim (POA) and Point-of-Impact (POI) intersect at two points: early and later in flight. Typically, you want to adjust the zero point so that where you are aiming and where the bullet will strike are close over a significant distance. Thus, you have a spectrum of ranges at which you will be accurate within a few inches.

In some cases your shooting distances may far exceed the overlap between POA and POI. In that case, you should make the weapon accurate at the target range you are most likely to encounter.

Test, Test & Test

Test repeatedly in three-shot groups, adjusting the weapon according to your results. Use the same factory ammunition or carefully constructed reloads every time, at the test bench and when engaged in the field.

Try to limit the variables with each testing session. Go at the same time of day, in the same weather, using your usual mode of dress, etc. Later during practice, you will deliberately alter these variables to improve your coping skills.

Ranging and Sizing

Making determinations of target size and range requires a keen eye for detail because images may appear quite small at a distance. Conversely, your target may be larger than the segmented portion of the reticule. Thus, arriving at accurate reading requires you to make an educated assessment. Here are a few pointers:

Multiply & Divide

Suppose your target is less than one graduation or is one plus a fraction. Compare the fraction with the next whole segment on the crosshair. Is it a forth, half, three-quarters?

What if your target is larger than the graduated portion of the crosshairs? Most scopes only span about 10 graduations along each axis (5 on either side of center for both vertical or horizontal). Position the scope so that one side of the target is at the edge of the dots or lines. How much of the target image is off the graduated portion? Imagine the dots or lines continuing. How many would there be? Another tactic is to divide your subject in half or into quarters and measure a section. Then multiply your reading accordingly to obtain the correct product number that represents the whole.

Increase Your Average

It may be difficult to assess the size or proximity of a target if it is standing on a hill, positioned at an angle, or shifting posture. In this case, it may be useful to take multiple measurements and average the results to obtain a more accurate product. Suppose you are targeting a pronghorn buck that is grazing on a hill. This animal is known to be about 36-40″ high at the shoulder. Use your reticle to measure the height from the shoulder to the front hooves. Now, readjust and evaluate the distance from the top of the hind quarters to the rear hooves. Add the two numbers and divide the sum by two. If your final value is 6 MOA, the buck is approximately 600 yards distant.

You can use the same technique when the subject has assumed two different stances while you are watching.

Scale

What if your target is standing near a known value, such as a fence line. Livestock fences average about 50 inches in height. Compare your subject to this and calculate accordingly.

Non-Graduated Reticles

Some reticles have only plain crosshairs but that need not defeat your purpose. Perhaps you are evaluating a black bear at 200 meters. While keeping the rifle very steady, put the crosshair at the shoulder of your target. Now use the elevation turret to slowly adjust the crosshairs halfway down to the paws while counting the clicks. You may need to estimate if it is standing in ground cover. Suppose it was 25 increments of 1/10th mil. Your subject is approximately 80 cm or 36 inches tall.

Holds and Windage Adjustments

Calculations do not always turn out clean and even. Sometimes the firing solution falls between adjustments. Suppose, for example that you need a vertical adjustment of 7.5 cm at 300 meters. Since each tenth of a milliradian is equal to 3 cm at that distance, there is no whole number of adjustments or “clicks” that would equal the necessary deviation. In order to compensate, you must perform a hold or hold-over. Making holds can be difficult, since you must estimate how much to aim above your target at a given distance to account for the adjustment. In the previous example, adjusting the vertical turret two increments up would elevate the POA 6 cm. Your hold must produce an elevation of 1.5 cm to complete the solution. Looking through a scope at 300 meters, this might be barely the thickness of the crosshair!

Holds are not always made because the solution lay between clicks. Suppose you are sitting on a powerline slash and an eight-point, white-tail buck crosses your field of vision at 150 yards. He will be back in the woods in a matter of seconds. There is no time to adjust your scope before you take the shot. If your rifle is zeroed at one-hundred yards, you will need to compensate by estimating how much to aim over your target for a strike.

Likewise, windage adjustments must sometimes be made on-the-fly. This is also referred to as Kentucky windage, no doubt a reference to the famed Kentucky frontier rifle and the skill of the men who used it. If you are compensating for a wind drift of 7.5 inches to the left at 300 yards, two clicks would bring you approximately six and a quarter inches of change. You would need to adjust your POA slightly to account for the remaining inch and a quarter.

Kentucky windage is used not only to account for motion of the air but also in leading a fast moving subject such as a bird in flight. Even though your target is moving much slower than a bullet, it will not be in the same place when the bullet arrives. You must aim ahead of your target enough to compensate for its forward motion while the bullet travels down range. Leading a moving object is a complex topic and performing it well is an art acquired over time. While it is beyond the breadth of this article, there are many fine writings available to instruct you.

One very useful tool for developing skill at windage adjustments is the Beaufort scale. It uses a series of common observations to estimate wind speed. One way to make your judgment of wind speed acute is to train with an anemometer. Digital anemometers accurately measure wind speed and are very affordable. Once you have used such a device to calibrate your perception of the wind, you can make precise calls on-the-fly with nothing but your five senses.

The Beaufort Scale

1mph-3 mphSmoke moves in direction of wind, slight movement of grass. 4 mph-7 mphWind felt lightly on the face *Very Accurate* 8 mph-12 mphLeaves turn, twigs and treetops will be in motion. 13 mph-18 mphLoose paper, dust, and paper will blow around, small tree branches will move. 19 mph-25 mphLarge tree branches move, entire trees will sway if small. 25 mph-30 mphLarge branches will be in constant motion and walking against the wind becomes difficult.

Between the Lines

Fine shooting is both a science and an art, which is why skilled shooters are so highly respected. There is much that falls between the measurements and calibrations. Equipment factors such as scope mount, action type, barrel length, rifling twist rate, bullet configuration, fouling and even barrel flux resulting from high temperature-among others-all affect placement. Your strength, visual acuity, breathing, shooting position, steadiness and mood determine your mastery over the weapon. Add situational variables including wind, altitude (which changes air density), luminosity, visibility, angle of inclination, distance and so on, and you have an infinitely fluid equation that results in a different answer every time. How well you control and interpret these elements will make the difference between a hit and a miss.

One way to improve your skill is to practice with known target sizes, at given distances, under varying conditions. Deliberately set up so that the target image is too small or too large, the wind and light are different, you are shooting up or down hill, etc. How does a 125 cm target look at 400 meters? What about a 9 inch target at 100 yards? How does your perception change in low light at dawn or dusk? What happens when you are shooting up toward your target?

This sort of practice will gradually calibrate your eye and your mind until it becomes an extension of the scope. You will, in effect, become one with your weapon. In fact, the truth is that YOU are the weapon. The rifle is merely a tool.

Use the information you have obtained here to improve your performance. Happy shooting!

This article is the outcome of much research and the first-hand practice of many shooters. However, individual experiences vary. If you have results that differ from ours or conflict with our findings, we would love to hear your perspective.

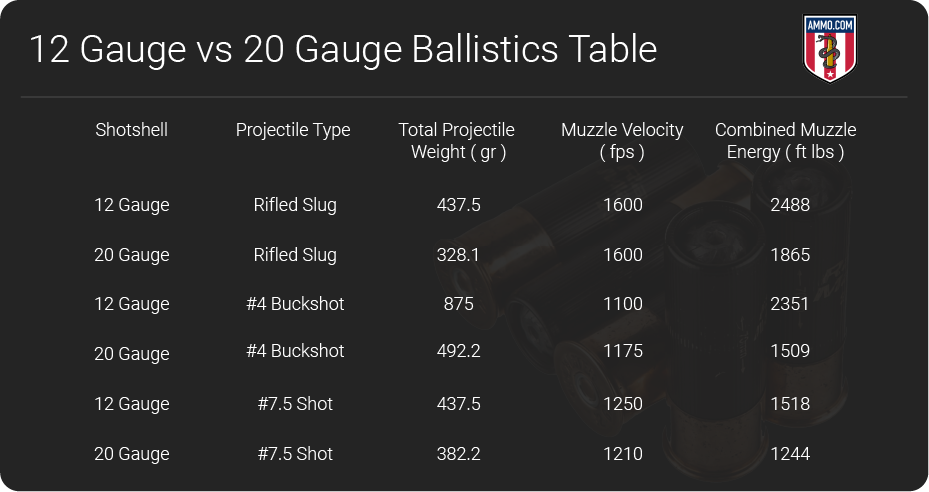

The versatility of a shotgun cannot be matched by many other types of firearms. You can select from a wide variety of gauges, barrel lengths, chokes, shot sizes, and more. This allows a shooter to utilize a shotgun for a multitude of purposes like hunting, home defense, and sporting clays.

The versatility of a shotgun cannot be matched by many other types of firearms. You can select from a wide variety of gauges, barrel lengths, chokes, shot sizes, and more. This allows a shooter to utilize a shotgun for a multitude of purposes like hunting, home defense, and sporting clays.

![Air gun 101: The differences between .177 & .22 – Which jobs they do best ? [Infographic]](https://airgunmaniac.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/1773-150x150.jpeg)