Want to buy the Best Thermal Scope for your rifle? We have you covered with a comprehensive, constantly updating list of quality Thermal Scopes on the market.

We have all price ranges on our list, so you can be sure to find something in your price range and feature set.

Table of Contents

What is thermal imaging?

Thermal imaging is a type of optical technology that measures the amount of heat radiation given off by living objects.

It works by capturing the infrared light that is emitted from the heat of a target, and this is then converted into an electrical signal that creates an image of the target on a display.

Thermal imaging scopes are useful in any kind of lighting condition and can be used during the day and at night, even in total darkness.

They do not require external light sources, are unaffected by glare, and can be used to see through dust, smoke, and fog.

However, they are pretty expensive and may require additional training to interpret the images correctly.

Best Thermal Scopes for 2024

ATN ThOR 4

The ATN ThOR 4 thermal scope is an excellent option for those looking for a reliable thermal scope in 2024.

This thermal scope is packed with features that make it an ideal choice for both hunting and tactical operations.

The 4th generation dual core thermal sensor provides ultra-sensitive detection and better contrasts.

The scope also has recoil-activated video, a one-shot zero, and ultra-low power consumption.

The ATN ThOR 4 features a built-in laser range finder, dual-stream video, and a new ultra-sensitive next-generation thermal sensor which lets you view and record at never before seen high resolution.

ThOR 4 series of thermal scope features a suite of applications like a built-in ballistics calculator, and it features recoil-resistant components and an expandable MicroSD slot that lets you record up to 256 gigabytes of photos and video on your device.

All these features make the ATN ThOR 4 an excellent choice for 2024.

Sig Sauer Echo 3

The Sig Sauer Echo 3 thermal scope is an excellent choice for anyone looking for an affordable, yet high-quality thermal scope.

The Echo 3 offers a wide variety of features that make it a great choice for an all-purpose thermal scope in 2024.

One of the Echo 3’s best features is its reasonable price tag. With two variants available, one with 1-6x magnification and one with 2-12x magnification, it is possible to acquire an excellent thermal scope without breaking the bank.

With 8 color palettes and 6 brightness settings, users are able to adjust the image to fit their needs.

The Sig Sauer Echo 3 also provides excellent battery life and a motion-controlled battery monitoring system, called MOTAC.

This system helps conserve battery life and helps ensure that the optic will power back on when needed.

The Echo 3 utilizes two CR123 batteries that last for up to 6 hours.

Finally, the main eye-catching feature of the Echo 3 is its large open screen. This feature allows users to keep their situational awareness high and makes the optic easier to use on the fly.

These features make the Echo 3 the best overall thermal scope for 2024.

Burris Thermal Riflescope

The Burris BTS 50 Thermal Riflescope is an excellent choice for thermal rifle scopes in 2021.

Its durable design and one-button control make it one of the most user-friendly thermal scopes available on the market.

With a 3.3-13.2 magnification range, a 400×300 pixel thermal sensor resolution, and a 50 Hz refresh rate, the Burris Thermal Riflescope offers a clear sight picture for hunting a variety of animals.

Its Hot Track feature allows the device to quickly and easily recognize the hottest object in the reticle’s zone and stick with it as it moves around.

The Burris Thermal Riflescope is also lightweight and compact, and its mounting system makes it easy to attach to a Picatinny rail.

Burris Thermal Riflescope comes with a 3-year warranty.

This makes it a great option for those who want an affordable and reliable thermal scope for their nighttime shooting setup.

Pulsar Thermion 2 Pro

The Pulsar Thermion 2 Pro is a powerful thermal imaging riflescope that offers a sleek design and a built-in laser rangefinder.

Featuring a 640×480 microbolometer resolution and an AMOLED display with 1024×768 resolution, this scope can detect heat signatures up to 2,000 yards away.

It includes a powerful laser rangefinder with a range of up to 875 yards, Wi-Fi connectivity to upload data to the Stream Vision 2 App, 10 reticle shapes in 9 color modes, Picture-in-Picture mode, and 5 unique shooting profiles.

It also boasts 10 hours of battery life, IPX7 waterproof rating, and can withstand calibers from 12 gauge, 9.3×64, and .375 H&H.

This scope is ideal for hunters who need precision and accuracy in any weather condition.

AGM Rattler TC19

The AGM Rattler TC19 is a great thermal scope for 2024 due to its affordability, impressive detection range, and versatility.

At under $1000, it’s a great value compared to its competitors, with a useful detection range of up to 650 yards.

It also features a FLIR Tau 2 sensor with 384×288 resolution, which allows for very crisp and detailed thermal imaging even at long distances.

The scope can also be used as a riflescope or a handheld monocular, with a digital zoom of up to 8x magnification.

It has the added benefit of being able to be connected to an external 5V battery pack via USB, increasing the usable battery life.

All of this makes the AGM Rattler TC19 a capable and affordable thermal scope for 2024.

Steiner NightHunter S35

The Steiner NightHunter S35 is an ideal thermal scope thanks to its unbeatable combination of features, performance, and price.

It has a high-resolution sensor of 640 x 480, a fast refresh rate of 12 micron/50 Hz, digital zoom of 2x and 8x, a long battery life of 4.5+ hours, and a lightweight 2.25-pound design.

It also offers durable aluminum housing and both first- and second-plane reticles, allowing the user to accurately and precisely identify targets in the dark.

Its price of under $5000 makes it an affordable option for those who need a reliable thermal scope.

With its reliable performance, high-quality components, and reasonable price, the Steiner NightHunter S35 is the perfect thermal.

ATN THOR LTV

The ATN ThOR LTV is a thermal rifle scope that has been gaining popularity in the shooting community because of its great price point.

This scope provides users with a 1280x720p HD display with Black-hot and White-hot modes, a one-shot zero feature for easy adjustments in the field, and 10+ hours of continuous battery power.

It is constructed with a hardened aluminum alloy and has a weather-resistant IP rating, making it prepared to face any adverse weather conditions.

It features the acclaimed 68 MOA circle dot reticle, which is known to offer the most intuitive ranging capabilities available.

With its excellent features and affordable price, the ATN ThOR LTV is perfect for both experienced and novice hunters and shooters alike.

It is a great product that combines both quality and affordability, making it a popular choice for anyone looking for a thermal rifle scope.

Fusion Thermal Avenger 40

Fusion Thermal Avenger 40 is a thermal scope that was designed around the Keep it Simple stupid menu system that Fusion Thermal is known for.

The Avenger 40 features a three-button control system as well as an alloy housing. The 40mm Ultra HD objective lens provides a great sight picture. The sensor is a 384×288 12-Micron thermal sensor and provides a top-notch thermal image.

A quality QD tactical scope mount is included and this optic is backed by a five-year transferable warranty.

What are the benefits of using a thermal scope?

Improved Target Acquisition and Acquisition

Using a thermal scope can drastically improve target acquisition and range.

Thermal scopes help with three things: detection, recognition, and identification.

Thermal imaging requires no light to function, which provides a distinct advantage in dense vegetation, under cloud cover, and during moonless nights.

Thermal scopes can detect targets up to 2,000 yards away, recognize the difference between a hog and a calf or spot a weapon up to 500 yards away, and identify a person or animal up to 200 yards away.

Furthermore, thermal scopes have customizable reticles and color schemes, as well as a one-shot-zero feature and can save profiles for multiple weapons or ammunition.

All of these features help to improve target acquisition and range.

See in Low Light Conditions

Thermal scopes help see in low light conditions by detecting heat emitted by a target and displaying it as a visible image.

This allows people to observe their target clearly, even in complete darkness or foggy weather.

Thermal scopes are also especially useful for hunting because they are not affected by camouflage or other obstructions, and can detect a target’s heat signature at farther distances than night vision scopes.

They can be used during the day or night, while night vision scopes are not designed to be used in daylight.

Detect and Track Moving Targets Easily

Thermal scopes offer a significant advantage in detecting and tracking moving targets.

The key benefit of a thermal scope is its ability to detect heat emitted by an object, which is why they are able to pick up and track moving targets better than other types of scopes.

This means that a thermal scope can be used to detect and track animals, people, vehicles, and other moving objects even in conditions where other scopes might struggle, such as cloudy days, in the brush, and at night.

Thermal scopes come with a wide range of features and capabilities, such as adjustable refresh rates, custom reticles and color palettes, and one-shot-zero capability, all of which support enhanced target acquisition and tracking.

Enhanced Accuracy and Reduced Guesswork

When shooting, accuracy and reducing guesswork are paramount.

A thermal scope can provide just that, as it provides a clearer image of the target and allows for easier ranging.

Thermal scopes are typically equipped with a built-in rangefinder, so you won’t need to switch back and forth between a separate device, like a rangefinder or rangefinding binoculars.

Some of the higher-end devices on the market have the ability to geotag your shot, recording the elevation, location, and speed when it was taken.

Thermal scopes often come with a 4-line crosshair reticle which allows for an easier adjustment for range to target, as opposed to a single-dot reticle which is better suited for short-range accuracy.

The thermal resolution on these scopes is also higher, providing a much clearer image of the target.

On top of this, the scopes are durable and lightweight, making them easy and comfortable to use, and they often have multiple zero settings, allowing you to save various zero settings to change your rifle’s zero with the press of a button.

These scopes can record your best shots and even share them with your friends. All of these features contribute to making the thermal scope a great choice for accurate, ethical shooting.

Ability to View Through Foliage and Other Objects

Thermal scopes provide a distinct advantage for viewing through foliage and other objects because they detect heat rather than relying on light like a night vision scope does.

The thermal scope can detect heat in heavily wooded areas that help animals or people stand out among the vegetation.

It does not need any additional light sources and can be used during the day or night, whereas daylight can potentially damage a night vision scope.

Thermal scopes have a much higher contrast between the target and the rest of the picture, making it easier to see, while night vision does not.

Thermal scopes can cut through camouflage or dense fog, while targets standing still are harder to recognize with traditional scopes.

Increased Safety Due to Target Detection

The use of a thermal scope significantly increases safety by providing the shooter with the ability to detect targets, even in the dark.

Thermal scopes aLLOW the shooter to identify potential threats in low light or no light conditions.

This allows the shooter to make an informed decision before taking any action, reducing the potential for friendly fire or collateral damage.

A wide field of view and long detection range of some thermals scopes allow for greater situational awareness, enabling the shooter to anticipate threats before they become imminent dangers.

Reduced Fatigue for the Eyes

Using a thermal scope reduces fatigue for the eyes by providing a super clear sight picture with a good refresh rate, a compact design, an adjustable refresh rate, and an awesome resolution.

The efficient size and weight of the thermal scope also enable users to enjoy longer use without the burden of carrying a heavy device.

Moreover, the optics of the thermal scope provide up to 6X or 12X magnification with resolutions of up to 640×512, allowing users to have an enhanced visual experience while reducing eye strain.

What to consider when choosing a thermal scope?

Here are a few good ideas to keep in mind while you’re shopping for a thermal scope.

Purpose and use

A thermal scope is an optical device that uses digital sensors and computer processors to measure and display the differences in heat radiation as various colors and contrast.

It is used as a target spotting scope, allowing the user to pick out targets by their heat signature in dark conditions and through weather conditions such as rain, fog, and snow.

Thermal scopes are also known as Forward-Looking Infrared (FLIR) scopes and can be handheld or mounted to a firearm.

They can also be used to record photos and videos, making them a valuable training tool in a tactical setting, or be used to record your hunt.

Price

Thermal scope price ranges are quite wide: you can find some units under the $1,000 mark, but these are rare to find.

Most thermal scopes on the market will cost at least $1,000, and some will exceed $5,000 and even reach up to $10,000.

If you’re looking for the best bang for your buck, you’ll likely be shopping in the $1,200-$2,500 range, but if you have the budget for it, then you could even look at some of the higher end models.

It’s important to keep in mind that these are not night-vision units, which can cost only a few hundred dollars since thermal scopes depend on a rare-earth element called germanium, which supplies temperature-sensitive glass for them.

Features

When choosing a thermal scope, it is important to consider several key features.

These include lens size, zoom, refresh rate, battery life, Wi-Fi capability, additional features such as Bluetooth technology, streaming, laser rangefinders, GPS, compasses, and ballistic calculators, and video recording capabilities.

Lens size will depend on the range you need to shoot at, while zoom will determine how close you can get to the target.

Refresh rate is important in order to get a clear picture, and battery life will determine how long you can use the scope without interruption.

Wi-Fi capability will allow you to stream video and connect to other devices, while additional features like Bluetooth, laser rangefinders, GPS, and compasses can add convenience.

Finally, video recording capabilities will allow you to capture and replay images. It is important to consider all of these features in order to choose the best thermal scope for your needs.

Quality and Reliability

Image quality is perhaps the most important, as this will determine how clear and accurate the sight picture is.

You should also look at the range of the scope, and make sure it can detect heat signatures out to the distances you need.

Pay attention to the materials used in the scope’s construction, as they should be extremely high-quality, as well as the pixel pitch and thermal resolution.

In addition to these qualities, reliability is also an important factor to consider. Look for a scope with a generous warranty length and positive customer support reviews.

Certain thermal scopes can come with bonus features such as Bluetooth technology, Wi-Fi streaming, and video recording capabilities.

While these features can be helpful, they are not necessary for good operation.

Ultimately, it is important to choose a thermal scope that provides the features you need at a reasonable price.

Optical Quality

Optical quality is of paramount importance when choosing a thermal scope. Good optics will ensure that you get a clear, high-quality image with minimal distortion.

The lens should be made of specialized germanium crystals, which absorb less light from the infrared spectrum.

This will allow you to capture more detail at higher magnifications. A larger objective lens, usually in the 50-60mm range, will also provide more signal and allow for better resolution.

It’s also important to consider the refresh rate of the thermal scope. A higher refresh rate means you will be able to detect movement more easily and accurately.

All of these features are essential for getting the most out of your thermal scope and ensuring you have the best possible experience.

Reticle and Zeroing

When choosing a thermal scope, there are a few important considerations that come into play. The reticle is one of the most important features to consider.

Reticle options vary from model to model and usually have different colors and styles that can also be selected to match your environment and target type.

Some reticles even feature a bullet-drop compensator, which can be a great aid to long-distance shooting.

Zeroing your thermal scope is also much easier than zeroing a traditional optic. Many thermal scopes offer a one-shot-zero feature, allowing you to set an accurate zero with a single shot.

Some models even allow you to save multiple presets, so you can have precise zeroes for different loads of ammunition on hand.

Overall, reticles and zeroing are two of the most important considerations when choosing a thermal scope.

Different reticle options and colors can help you better identify your target, and the one-shot-zero feature makes it easy to set accurate zeroes for multiple loads of ammo.

Field of View

The field of view of a thermal scope is the area the scope will allow you to see.

It is measured in degrees and typically ranges from 4 to 14 degrees, depending on the scope’s magnification.

Generally, the higher the magnification, the narrower the field of view. The field of view is important since it helps you recognize your target from farther away.

With a wider field of view, you can see more of the area around you, making it easier to spot targets.

The refresh rate of the scope also affects how quickly you can recognize targets and movements. Higher refresh rates allow you to see changes to the scene faster.

Weight and size

Weight and size are important considerations. With any optic weight can add unneeded stress to the shooter and weigh down your gun while trying to aim.

Making accurate shots is much easier with a lighter firearm and won’t fatigue the shooter.

Sensitivity and Amplification

Sensitivity is a key characteristic of thermal scopes that determines how well the scope can detect heat signatures of objects at a certain distance.

The higher the sensitivity, the further away the thermal scope can detect heat. Amplification is another key factor in determining the range and performance of thermal scopes.

Amplification increases the brightness of the image, allowing for better detection of heat signatures in low-light conditions.

It also helps to magnify the image and make it easier to identify objects at a distance.

Batteries

When choosing a thermal scope, it is important to consider the battery life, charging time, and replacement battery costs.

Thermal scopes typically operate on lithium-ion batteries that are easy to replace and charge and the battery life for most quality thermal scopes is about 8 hours, which is normally sufficient for a single hunting trip.

However, if a person is going on a longer trip, a spare battery will be necessary.

Some thermals can use external battery sources, which can mix disposable and external battery sources.

When comparing thermal scopes, it is important to take into account battery life as it can make a huge difference in the field.

Thermal scopes have become more efficient, but battery life generally ranges from three hours to twenty-four hours.

Some thermals come with spare batteries while others are rechargeable.

It is important to read up on the scope before purchase to make sure the battery life will last as long as needed, also consider the cost of replacement batteries.

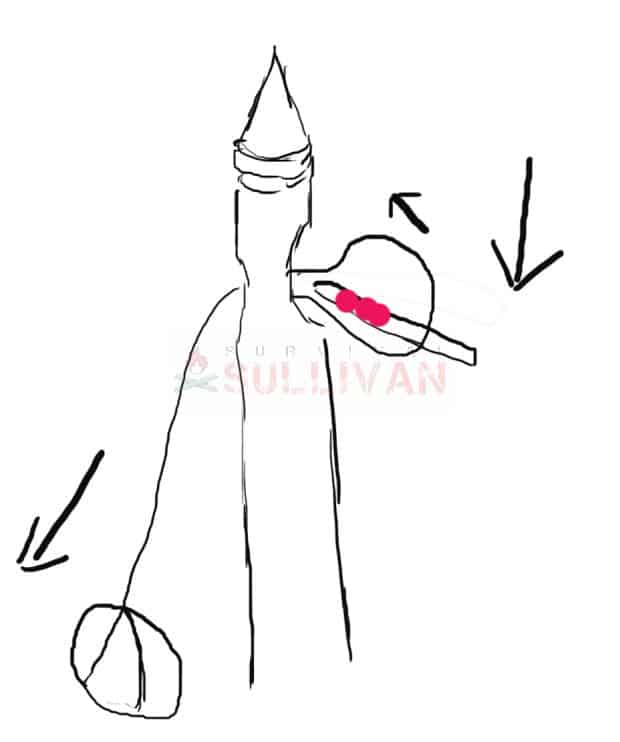

Mounting options

Mounting options for thermal scopes vary depending on the specific scope.

Thermal scopes can either be designed to be mounted directly onto a rifle’s Picatinny rail or require special gear, such as a mounting base with rail segmentation and scope rings with the correct mounting height.

Clip-on thermal devices can also be used to mount a thermal scope onto a rifle that only has dovetails.

Monoculars, on the other hand, are handheld or mounted on helmets and are used purely for observation.

They cannot be zeroed and do not feature reticles, unlike traditional thermal scopes.

Some examples of thermal scopes include the Burris Thermal Riflescope, SIG Echo3, Trijicon REAP-IR, Thermion XP50, ATN Thor 4 384, AGM Python TS50-640, and Steiner Close Quarter’s Thermal Sight.

Each of these scopes has its own mounting considerations, so it is important to do research on the specific scope before making a purchase.