In the southwest corner of Michigan sits a small but significant north-country stream. The St. Joseph River, a turbid Lake Michigan tributary that winds through large portions of the Mitten State and Indiana, draws strong runs of popular Great Lakes gamefish, like walleyes and steelhead. These seasonal migrations attract the attention of serious anglers from across the Midwest. In turn, fishery personnel react accordingly by using science and good judgment to achieve sustainable fish populations.

In the southwest corner of Michigan sits a small but significant north-country stream. The St. Joseph River, a turbid Lake Michigan tributary that winds through large portions of the Mitten State and Indiana, draws strong runs of popular Great Lakes gamefish, like walleyes and steelhead. These seasonal migrations attract the attention of serious anglers from across the Midwest. In turn, fishery personnel react accordingly by using science and good judgment to achieve sustainable fish populations.

What is less well-known is that the St. Joe plays home to a healthy northern population of flathead catfish, a fish gaining in popularity with fishermen. Because of increasing pressure on these fish, managers are interested in learning more about St. Joe’s flatheads to form smart management strategies.

Dr. Trent Sutton, associate professor of fisheries biology at Purdue University, and graduate student Dan Daugherty, conducted research projects in 2002 and 2003 that explored the St. Joe’s flathead catfish movements and habitat. They used ultrasonic telemetry to determine habitat use and movement, and recorded over 640 observations. Transmitters were implanted into 39 flatheads between 17 and 44.5 inches (2.9 to 39.6 pounds).

“What makes our work unique from other Midwestern studies is that we’re the first to have done anything on flathead populations in the Great Lakes watershed,” says Sutton. “The St. Joe flatheads are quite unique in that they are far out of their core range. If you look at a map of geographic distribution, this group is isolated all by itself in the northeast portion of the normal range. These Michigan fish stand out like a little patch on the map, whereas everything else is connected.”

The St. Joe is a smart target for study because it contains a healthy population of flathead catfish that see relatively low exploitation rates. And though these northern fish might grow as fast or get as large as their southern counterparts, the study remains important because other Great Lakes tributaries hold similar flathead populations that could benefit from the research.

In addition to the St. Joseph River, Michigan has flatheads in the Muskegon and Kalamazoo rivers, among others, and there are a handful of major Great Lakes tributaries in Wisconsin, like the Fox and Wolf rivers, that hold them, too. All these waters have viable populations that deserve sound management, and the only way to improve it is to have a good understanding of the dynamics of one flathead population that adequately represents others within the region.

Anglers benefit from this research, too. Findings from fishery science eventually arrive on anglers’ laps in the form of trade publications and cutting-edge angling media, like In€‘Fisherman. With regard to Sutton and Daugherty’s work on northern flathead catfish, research brings to light key information that eliminates much of the work in the game of flathead catfishing.

Habitat Through the Seasons

Understanding habitat requirements is crucial to completing any fishing puzzle. Interestingly, Sutton and Daugherty discovered that the preferred cover of flatheads changed by season. “Complex wood structures in the form of logjams comprise the most often used form of cover for adult flathead catfish throughout the warm water seasons,” says Sutton. “Nearly three-quarters of the observations found flatheads in sizeable logjams. Smaller fish tended to use riprap structures made from large, angular chunks of concrete. Obviously, the smaller fish would have smaller hiding requirements, so this works fine for young fish.”

Flatheads choose these areas because of the quality of the cover and hunting opportunities. Logjams tend to have larger openings that allow better movement and hiding opportunities for larger fish. Riprap, on the other hand, is much more uniform and typically holds smaller spaces that protect juveniles from large predators.

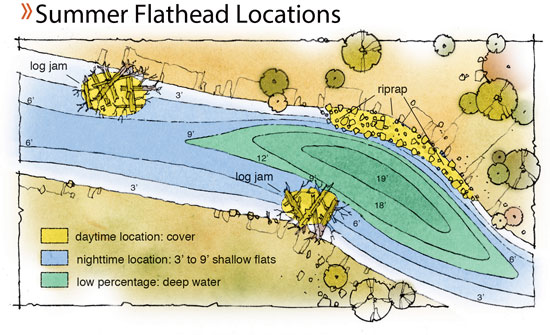

Gravel-bottomed areas played a negligible role in spring, summer and fall. And the presence of deep water was a minor factor for determining flathead catfish location during the bulk of the open water season. In fact, Sutton’s research showed that St. Joe cats have a distinct preference for water shallower than 9 feet for use as a home base in spring, summer, and fall.

Everything changed, though, when flatheads made a major move from summer hunting grounds to wintering holes. Pools with rocky bottoms and deeper than 12 feet attracted flatheads when winter arrived, likely a result of reduced current in the greater depths. Flatheads held in these pools throughout the winter months, barely moving until spring.

Seasonal Flathead Catfish Movements

The Purdue researchers also found that St. Joe flatheads showed trends in seasonal movement. With the onset of spring’s warming temperatures, fish began leaving winter hibernating holes for familiar warm-water hangouts.

The Purdue researchers also found that St. Joe flatheads showed trends in seasonal movement. With the onset of spring’s warming temperatures, fish began leaving winter hibernating holes for familiar warm-water hangouts.

“Once water temperatures reached about 50ºF, flathead catfish began moving around,” says Sutton. “Fifty degrees is a kind of magical number for many fish species, and it works well for the flathead catfish, too. But what’s more interesting is that flatheads coming out of winter dormancy, in many instances, move back to the very structures they used the previous year. In our studies, most of the tagged fish returned from wintering areas to their original capture locations from the previous summer over a two-week period. In fishery research terms, this behavior is referred to as high site fidelity.”

Distances covered by St. Joe’s flatheads in spring were the greatest of the year, averaging over 1,500 yards. In May and June, these fish moved back and forth from riprap to log structures on a regular basis. Some of this movement is attributable to migrations from wintering areas to summer homes, and some occurred as a result of spawning rituals, as both rocky and woody features are frequently used by flatheads for spawning zones.

During the heat of summer, the tendency for long-distance movement slowed. Most of the time, when flathead catfish reached hot-weather haunts they stayed close to home, foraging extensively on nighttime forays in the immediate area of their base. At this time, the majority of fish moved less than 3/8 of a mile from the original capture site.

Fall observations once again showed much movement of flathead catfish as they transitioned from summer to winter sites. Flatheads stayed in summer areas until water temperatures dropped to about 50ºF, at which point they moved an average of over 1,200 yards, with industrious specimens moving up to nearly 4,000 yards. Once they reached where they wanted to spend the winter, they remained inactive until the following spring.

“These fish become absolutely dormant at that time,” says Sutton. “Scuba divers have found flatheads in deep wintering areas, all lined up in single-file on the bottom, each fish acting as a sort of current break for the next. They’re covered with mud or silt and not moving at all.”

Sutton believes that what pushes flatheads toward deep water is temperature, more so than photoperiod (the change in daylight hours in a twenty-four hour period). Specifically, he points to the magical 50°F mark, which is so important in triggering migration tendencies in other gamefish, like walleyes, to be the catalyst that drives them to make location changes in both spring and fall.

Interestingly, the movement of flathead catfish was non-directional during all seasons. This is somewhat different from the way anglers understand more popular migrations of river fish. Walleyes and steelhead, for example, show distinct upstream migration trends prior to the spawn and downstream migration tendencies during postspawn. But not St. Joe’s flatheads. When there was a distinct seasonal movement underway, some fish went upstream and some went downstream; there was no clear trend in direction.

Daily Flathead Catfish Movements

Daugherty tracked the daily movements of St. Joe flatheads for two months in the summer of 2003. He observed that flatheads showed a distinct preference for moving out of cover to stretch their fins, particularly at night. And though the overall movement on these forays was often considerable, the fish usually stayed close to home.

“Most people think of catfish as wait-and-watch predators, but flatheads actually move around and actively hunt for food,” says Sutton. “It’s probably easier for them to do this in more open areas outside their woody daytime cover. Flathead catfish have eyes that are located on top of their head and a lower jaw that undercuts, which shows that these fish are clearly approaching their prey from below. So they’re cruising low in the water column, looking up for something that looks good to eat.”

Throughout the nighttime feeding period, flatheads chose mild, main-river currents for their hunting grounds and stayed out of backwater areas. The trend was to move out from cover toward relatively shallow (less than 10 feet) open areas to feed. By dawn, the St. Joe flatheads were neatly tucked in loggy structures and, most times, in the very ones they left the night before. During daylight hours, they remained in logjams and other woody debris and showed little movement.

Flathead Science: Angling Tips for Small Northern Rivers

Science has helped us make better decisions on how and where to spend our fishing time. In recent years, traditional thoughts on the areas fish call home have been called into question. With regard to flathead catfish, it seems that deep water isn’t always their home, especially during summer. Purdue researchers Trent Sutton and Dan Daugherty found that summer flatheads occupied the shallowest water of the year in anywhere from 3 to 9 feet. So, for warmwater anglers bent on maximizing fishing time, fish shallow in small to medium northern rivers. Research suggests that riverbend pools can be low-percentage water in the dog days.

Science has helped us make better decisions on how and where to spend our fishing time. In recent years, traditional thoughts on the areas fish call home have been called into question. With regard to flathead catfish, it seems that deep water isn’t always their home, especially during summer. Purdue researchers Trent Sutton and Dan Daugherty found that summer flatheads occupied the shallowest water of the year in anywhere from 3 to 9 feet. So, for warmwater anglers bent on maximizing fishing time, fish shallow in small to medium northern rivers. Research suggests that riverbend pools can be low-percentage water in the dog days.

It’s equally valuable to know that flatheads are intimately familiar with the lay of their neighborhoods. Big cats spend their feeding hours roaming well-known areas close to home, which in most cases comprise large, complex logjams. When prospecting new water for big fish, stay within about 75 yards of any sizeable woody structure. Live baitfish (sunfish, suckers, or shad) in the 6- to 8-inch range anchored in place a foot or two off bottom is a dependable option for summer flatheads.

For eater-sized specimens, check structures having smaller crevices and hiding areas like riprap or rock and wood combinations that allow juveniles to escape adult predators. Downsize the offering; 3- to 5-inch minnows are good finger-food for 18-inch and smaller flatheads. Just remember to stay close to the rocks when presenting baits.

Feeding occurs most when the sun goes down — therefore, the bulk of angling effort for flatheads should take place during the night. During daylight hours, Daugherty’s flatheads showed a distinct preference for inactivity. For anglers who shun the night, however, floating a big livebait near woody cover might get a flathead’s attention, especially during the warmest days of the summer.

Whereas cold-water channel cats are rising in popularity with die-hard whisker chasers, flathead anglers would probably do better to sharpen hooks and pour lead. Daugherty found that flatheads didn’t move when water temperatures dipped below 50°F. By that time, St. Joe cats had found their wintering homes at the bottoms of deep holes and scour pools. While cold-water flatheads can be caught, they’re often congregated and vulnerable to snagging, both intentional and unintentional. If cold water is your game, tread lightly on this precious resource.

![Air gun 101: The differences between .177 & .22 – Which jobs they do best ? [Infographic]](https://airgunmaniac.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/g44-150x150.jpg)