It is easy to forget the days like the one the duck hunters died. It is easy to forget that there was a time—not so very long ago, really—when there was no Gore-Tex, no Thinsulate, no neoprene and no polypropylene for duck hunters. There was a time when outboard motors, far from the sleek and powerful marvels of today, were crude, cumbersome beasts, unreliable under the best circumstances and all but useless under the worst. There was a time when there were no cell phones, no emergency beacons, no Flight for Life helicopters.

There was a time, too, when there were no weather satellites, no telemetry to provide data that could be plugged into sophisticated formulas and fed into supercomputers for timely forecasts. Indeed, that the weather could be predicted with any degree of accuracy then—November 1940, to be precise—seems almost miraculous, meteorology in those days being one part science and two parts the divination of omens, signs and portents. Nothing brings this into starker relief than the fact that, a little more than a year later, what appeared on radar to be a swarm of aircraft approaching the Hawaiian Islands was dismissed as some sort of malfunction by military officers who refused to trust this newfangled and unproven technology.

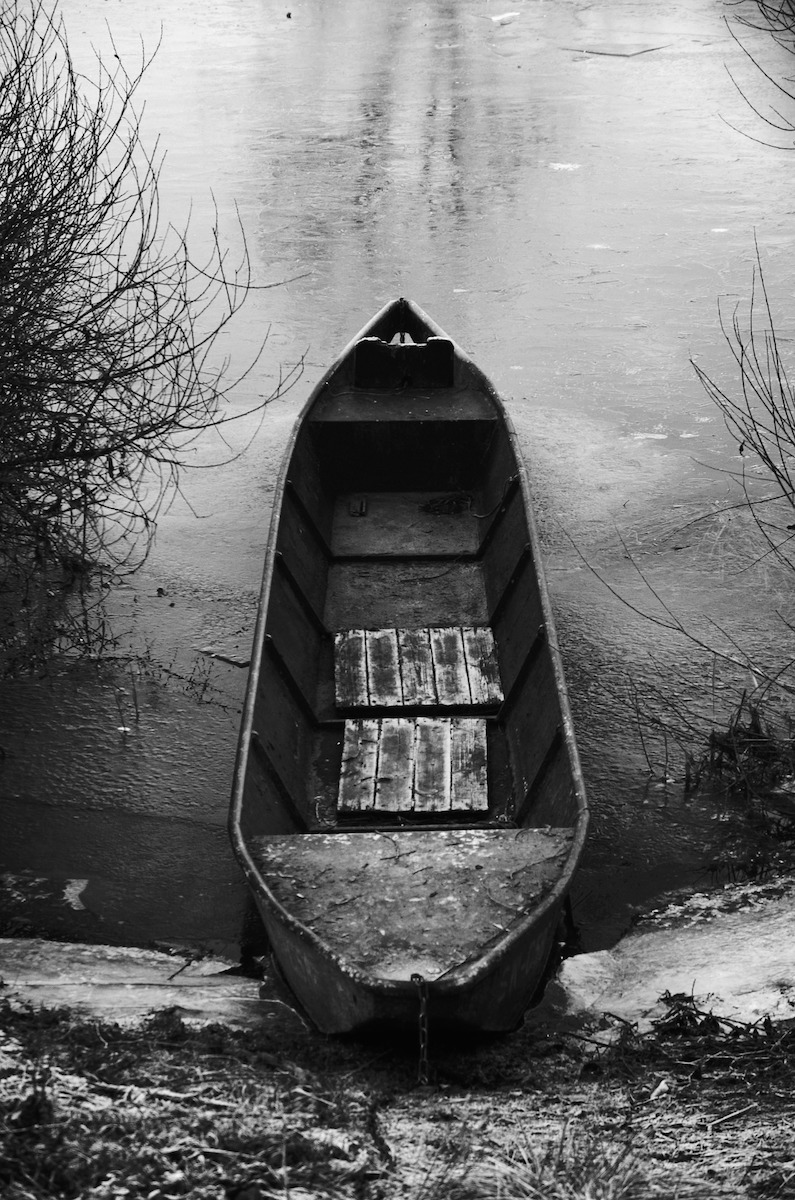

Of course, some things do not change with the passage of time, and one of those constants is the love of duck hunters for the kind of wet, raw, blustery, thoroughly miserable days that keep normal people indoors with the fireplace crackling and the teakettle whistling on the stove. And just as absence makes the heart grow fonder, the longer the duck hunter is made to wait for such a day, the hotter burns his pent-up desire to escape the sloughs and bays and marshes, and there—decoys artfully set, blind brushed and grassed, dog expectant and quivering, call poised to be pressed to lips—scan the lowering skies for birds that ride the wind.

The fall of 1940 had been a mild one in the Upper Midwest, an extended Indian summer of warm temperatures and little rainfall. In other words, the duck hunting had been disappointing. Oh, there had been the usual “local” birds in the early season—teal, wigeon, shoveler, the odd mallard—but without any heavy weather to set the migration in motion, the great flocks of northern ducks were still in the prairie provinces of Canada, fattening up for the long flight south. Hunters throughout the region, from the Dakotas across to Wisconsin, from Minnesota down to southern Illinois, were on pins and needles, knowing that the change in weather they so dearly wanted was overdue, that it could happen any day.

Finally, on Sunday, November 10, came a forecast that held promise. The outlook was for clouds, snow flurries, and colder temperatures. Wildfowlers were ecstatic, and what made this good news even better was that Monday, November 11, was Armistice Day—the predecessor to Veterans Day, and, for many people, a holiday. Although as holidays go it was a fairly somber one. The grinding effect of the Great Depression still lingered in the U.S., and in Europe. There, where just 22 years earlier the eponymous armistice had been signed, war raged once again.

Still, it’s not much of a leap to suppose that the typical waterfowler of the Upper Midwest, upon hearing the forecast on the radio or reading it in the local newspaper, felt blessed—even jubilant. Other concerns were pushed aside; nothing mattered now but getting ready for tomorrow’s hunt. Decoys, shell boxes, shotguns, and calls were checked and rechecked. Ditto for boats, motors, gas tanks, and oars. Clothes were carefully laid out; sandwiches were made, wrapped in wax paper and refrigerated; thermos bottles were placed next to coffee percolators. The dog was given an extra bit of food, because in a few hours he was going to be one busy retriever and would need all the energy and stamina he could muster.

Still, it’s not much of a leap to suppose that the typical waterfowler of the Upper Midwest, upon hearing the forecast on the radio or reading it in the local newspaper, felt blessed—even jubilant. Other concerns were pushed aside; nothing mattered now but getting ready for tomorrow’s hunt. Decoys, shell boxes, shotguns, and calls were checked and rechecked. Ditto for boats, motors, gas tanks, and oars. Clothes were carefully laid out; sandwiches were made, wrapped in wax paper and refrigerated; thermos bottles were placed next to coffee percolators. The dog was given an extra bit of food, because in a few hours he was going to be one busy retriever and would need all the energy and stamina he could muster.

The phone lines hummed as hunting partner called hunting partner, their voices crackling with excitement. They knew, with as much certainty as they knew anything, the ducks would be flying, and they aimed to be smack dab in the middle of them.

They got more than they bargained for.

In his magisterial Where The Sky Began: Land of the Tallgrass Prairie, John Madson describes the genesis of a Midwestern blizzard as a “temperature marriage” of cold, dry polar air sweeping down from Canada and warm, moist subtropical air welling up from the Gulf of Mexico.

“Since its primary component is wind,” Madson wrote, “the classic blizzard is essentially a phenomenon of the open lands—particularly the plains and prairies, where the topography offers little resistance to moving air and the great storms can run almost impeded. There may be more snow in northern and eastern forest regions, and certainly much cold. The difference between winter storms there and the classic prairie blizzard lies in the intensity of unbridled wind that plunges the chill factor to deadly lows, drives a blinding smother of snow during the actual storm, and continues as ground blizzards and white-outs long after snow has stopped falling. Depending on snowfall and wind, the storm may leave drifts three times as tall as a man and is usually followed by calm, silver-blue days of burning cold.”

That, in a nutshell, describes the blizzard that screamed across the Upper Midwest on Monday, November 11, 1940, devastating everything it touched along the way. The winds blasted at a constant 40-50 mph with gusts in excess of 80. More than 16 inches of snow fell in the Twin Cities, while more than 26 inches were recorded a few miles up the Mississippi River near St. Cloud. In LaCrosse, downstream on the Wisconsin side of the Mississippi, the barometric pressure sank to an all-time low. The temperature dropped 30 degrees—from above freezing to single digits—in two hours and continued to plummet from there. Windchills were virtually off the charts.

Nothing escaped the storm’s furious, relentless, indiscriminate wrath. Livestock perished by the hundreds of thousands. So many turkeys died in parts of Minnesota and Iowa that after the storm farmers were selling whole “fresh frozen” birds for 25 cents apiece. The losses to wildlife, especially pheasants, were spectacular. Communications and power were disrupted across thousands of square miles, and transportation was brought to an absolute standstill. Every town and village close to a main road became a refuge as stranded travelers sought shelter from the storm. Countless people opened their homes to complete strangers, providing whatever they could offer in the way of board and room.

But for some there was no shelter, no refuge. Motorists stuck in snowdrifts on remote stretches of road were buried alive in their cars, their frozen bodies not exhumed for days. On Lake Michigan, the freighter William B. Davock was sheared in two by monstrous waves.

The ferocity of the storm was almost beyond human reckoning. There are accounts of farmers who, after checking their livestock, could not find their way from the barn to the farmhouse. Disoriented, pummeled by the wind, with no visible landmarks to guide them, and no sense of east, west, north, or south, they wandered blindly through a roaring white hell. The lucky ones bumped into something recognizable and groped their way to safety. The unlucky ones didn’t.

Nearly everyone who survived the storm remarked on how incredibly difficult it was just to breathe. The air was so laden with moisture that it seemed as thick as syrup. And even when you were able to draw a deep breath, the cold seared your lungs like a red-hot blade.

This is what thousands of duck hunters, with their wooden skiffs and their cranky outboards and their canvas caps, found themselves caught in. Most of the world knows the Midwestern blizzard of November 11, 1940, as the Armistice Day Storm. To sportsmen, it’s simply the day the duck hunters died.

No one really knows how many people lost their lives as a direct result of the Armistice Day Storm. Although Time put the death toll at 159, the actual figure was probably closer to 200—and about half of them were duck hunters. According to John Madson, 85 duck hunters perished in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Illinois alone. As he wrote in Where The Sky Began, “Caught by the storm with little warning, they drowned as they tried to reach land, or stayed in their duck blinds as waves tore them apart, or simply died of exposure that night on the river islands out of reach of help . . .”

If a storm causing as much destruction and loss of life occurred today, someone like Sebastian Junger or Jon Krakauer would write a best-selling book about it. But while it certainly made headlines—a spread in Life was entitled “Midwest Tempest Strews Death By Land and Lake”—America was preoccupied with other matters. After the dead were buried, the damage was cleared, and the bereaved had ceased to mourn, life resumed more-or-less as usual. And the weather for the remainder of the winter of 1940-’41 was largely unremarkable.

But no one who was there would ever forget it. Nor did their memories, like photos left too long in a show window, pale with the passage of time. It was the persistence of these memories that, 45 years after the event, prompted a Minnesota man named William Hull to track down and interview more than 500 people who’d lived through the Armistice Day Storm. He then selected 167 of these accounts and assembled them into a book called, fittingly, All Hell Broke Loose.

Now in its 18th printing, it’s replete with tales not only of close calls and narrow escapes, but of countless acts of charity, generosity, selflessness, and heroism. (There are a number of humorous, Keillor-esque tales as well, such as the one entitled “Three Hours Digging Path to Outhouse.”) Not a few of these stories were told by duck hunters. While the specifics may differ slightly—some recalled seemingly endless flocks of divers like redheads, bluebills, and canvasbacks, while others remember wave upon wave of mallards—they all agree that they had never seen the sky so full of ducks. They agree, too, that there was nothing in the weather that morning to presage what was coming, that the storm was upon them almost before they knew what was happening, and that it was only by the grace of God that they survived when so many others did not.

Every sportsman who was there has his own wrinkle to add to the story. Cyril Looker of Fremont, Wisconsin,—in the heart of the wildlife-rich Wolf River bottoms—recalls standing on the shore near a power line cut and burning up two boxes of shells as the ducks poured into Partridge Lake. The kicker, notes the 83-year-old Looker, is that the birds—mallards and divers both—were flying beneath the wires.

The account that eclipses all the rest, though—and has made the Armistice Day Storm vividly and chillingly real for generations of sportsmen ever since—is the one written by the great Gordon MacQuarrie. Indeed, it’s entirely likely that if MacQuarrie, then the outdoors editor for the Milwaukee Journal, hadn’t been on the scene, the event would be little more than a footnote in duck hunting history. While a lesser writer might have filed a competent and informative report, MacQuarrie penned a masterpiece.

His story, under the headline “Icy Death Rides Gale on Duck Hunt Trail,” appeared on the front page of the Journal on Wednesday, November 13. It was filed from Winona, Minnesota, a Mississippi River town about 90 miles downstream from the Twin Cities. The river there is a sprawling, two-mile-wide wilderness of islands, oxbows, and backwater sloughs, and Winona was the epicenter of the disaster: At least 20 duck hunters died within 50 miles of the city.

“The winds of hell were loose on the Mississippi Armistice day and night,” wrote MacQuarrie. “They came across the prairie, from the south and west, a mighty freezing force. They charged down from the high river bluffs to the placid stream below and reached with deathly fingers for the life that beat beneath the canvas jackets of hundreds of duck hunters . . .

“The wind did it, the furious wind that pierced any clothing, that locked outboard engines in sheaths of ice, that froze on faces and hands and clothing, so that survivors crackled when they got to safety and said their prayers.

“Mother Nature caught hundreds of duck hunters on the Armistice holiday. She lured them out to the marshes with fine, whooping wind, and when she got them there she froze them like muskrats in traps. She promised ducks in the wind. They came all right, but by that time the duck hunters were playing a bigger game with the wind, and their lives were the stake.

“By that time men along the Mississippi were drowning and freezing. The ducks came and men died. They died underneath upturned skiffs as the blast sought them out on boggy, unprotected islands; they died trying to light fires and jumping and sparring trying to keep warm; they died sitting in skiffs. They died standing in river water to their hips, awaiting help; they died trying to help each other. A hundred tales of heroism will be told, long after the funerals are over.”

MacQuarrie told of Gerald Tarras, a strapping 17-year-old who’d gone hunting in the Mississippi bottoms that fateful day with his father, brother, a family friend, and their black Lab. They set up mid-morning in a drizzling rain; by noon they were trapped by six-foot waves, waves that pounded like huge iron fists and hurled freezing spray that turned instantly to boilerplate ice. The men beat on one another to try to keep warm, but it was a losing battle. At about 2 a.m. the friend uttered one last moan and died in Gerald’s arms. Gerald’s brother held out until 11 in the morning, but after 23 hours of exposure, he, too, succumbed.

Then, shortly after noon, a small plane flew over. Gerald waved, and the pilot signaled that help was on the way. Rescuers in the government tugboat Throckmorton arrived at 2:30—half an hour too late to save Gerald’s father. They found the boy crouched against a stump, holding his dog for warmth, fighting to remain conscious.

Max Conrad, the pilot who led rescuers to Gerald Tarras, was one of the true heroes of the Armistice Day Storm. Dozens of hunters would later acknowledge that they owed their lives to him. On Tuesday the 12th, with the wind still howling but the skies clear, he took off from his hangar in Winona to help find the hunters who hadn’t come home. Flying a redoubtable Piper Cub—and fighting to make even 20 or 30 knots of airspeed against the brutal headwinds—he scanned the frozen margins of the Mississippi for the living, but often as not discovered the dead.

When he located survivors—they were frequently huddled in the lee of a skiff they’d propped up as a windbreak—Conrad would circle low, cut the engine for a moment, and holler “Hang on! Help is coming!” A few minutes later, he’d return and, like manna sent down from heaven, drop a canister filled with sandwiches, whiskey, dry matches, and cigarettes. Conrad would then circle until the Throckmorton or one of the many rescue boats that had deployed in search of survivors could get a fix on the spot. He kept flying until 10 p.m. that night, and he was out again at dawn the following day.

There is no telling how many hunters died for the simple want of dry matches. But even that was no guarantee, as there was still the problem of finding dry fuel to burn. Many a prized Mason decoy went up in flames, and a group of 17 hunters stranded on the same island took turns shooting down limbs for firewood until their ammunition ran out.

The Mississippi River was not the only place where duckboats became sepulchres, of course. Two hunters died on Wisconsin’s Big Muskego Lake, barely 20 miles from downtown Milwaukee. One of these men was alone in his skiff, trapped by waves and ice. Toward the end, another party of hunters glimpsed him standing in his boat with his head tilted back, his arms stretched outwards, and his palms turned up. It was as if he was imploring God—or perhaps commending his soul to Him. While the other hunters, who themselves were fighting to survive, watched helplessly, the man slumped back into his skiff, leaned heavily against the gunwale, and went motionless.

His spirit, like the ducks that drew him out on that terrible day, had flown.

The author wishes to thank Howard Mead of Madison, Wisconsin, for his assistance in providing background research.