Researchers look to moose calves for answers

By Mike Lynch

Scientists are hoping a new study focused on moose calves will provide clues as to why New York’s moose population hasn’t grown as anticipated.

“We’re really taking a hard look at some factors that are potentially limiting our population in New York,” said senior wildlife biologist Paul Jensen, of the state Department of Environmental Conservation.

The DEC estimates the population to be between 550 to 900 moose in northern New York. The animals can be found anywhere in the Adirondack Park, but are most common in logged areas.

Moose returned to the Adirondacks in the 1980s after disappearing in the 19th century.

Scientists believe the biggest cluster is just north of Paul Smiths, where there are conservation easement lands and logging operations.

Jensen said scientists want to know why so many moose have populated this area, yet have lower numbers in some similar habitats.

To answer this question and others, scientists are tracking more than a dozen young moose, hoping to learn more about their movements and how they die.

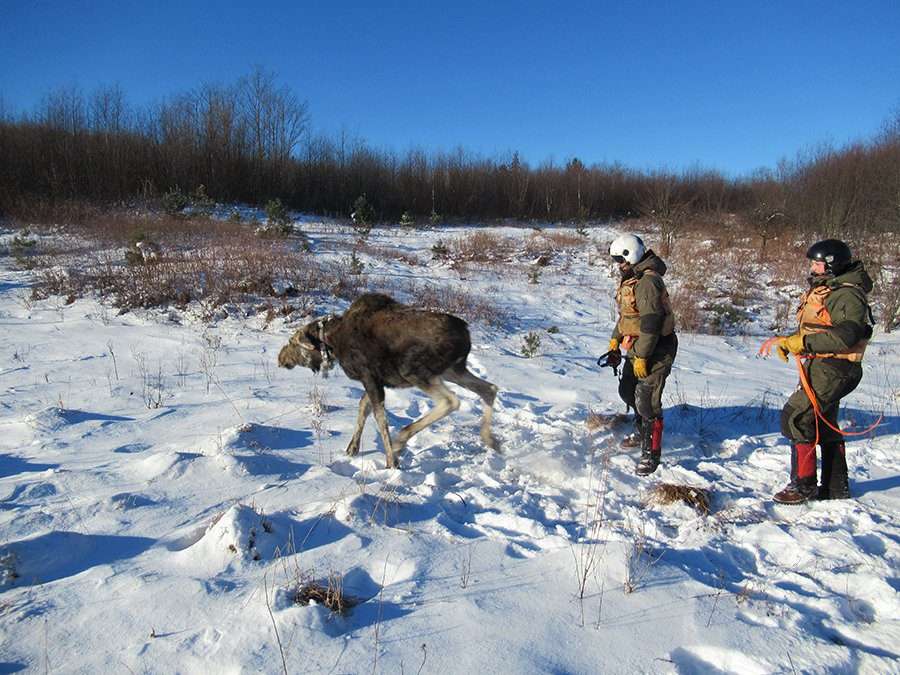

In January, researchers put GPS collars on 14 moose — 12 calves that are roughly six months old and two about 16 to 20 months old. Additional animals will be fitted in the future.

The collars track the animals’ movements, including when they leave their families at about 16 months.

In addition, when a moose dies, a field crew can locate it, and do an evaluation to determine cause of death. When possible, the team will recover it for a comprehensive necropsy.

Young moose can fall prey to larger animals such as black bears, but researchers want to learn more about parasites such as liver flukes, brain worms and winter ticks, and the diseases they pass on.

Scientists are particularly concerned about winter ticks, which have caused population declines in New Hampshire and Maine. Tens to hundreds of thousands of these parasites have been found on moose, causing them to weaken and die.

And calves have been found to be particularly vulnerable.

An article published in the Canadian Journal of Zoology in 2018 found that winter ticks were the No. 1 cause of death for moose calves studied in New Hampshire and Maine from 2014 to 2016.

As part of the New York study, scientists are also examining how much the ranges of moose and white-tailed deer overlap. Deer carry many parasites and diseases that afflict moose, including winter ticks, yet aren’t impacted as much.

To determine the range overlap, scientists will be monitoring trail cameras that were installed this past fall. They will also look at the images to look for hair loss on moose, a symptom of winter tick infestation.

They will also be examining white-tailed deer pellets and water sources to determine the presence of brain worm and liver fluke across the landscape. Larvae from these parasites are found in deer scat, where they are picked up by snails and then incidentally consumed by foraging moose.

DEC is partnering with Cornell University, the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, and Native Range Capture Services for this project.

The research has cost about $700,000 so far and has been funded by a Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration grant through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service that reimburses the scientists for their work. These funds are collected through federal excise taxes on firearms, ammunition, and archery equipment, and then apportioned to states for wildlife conservation.

Hunting moose is not allowed in New York because they are a protected species.