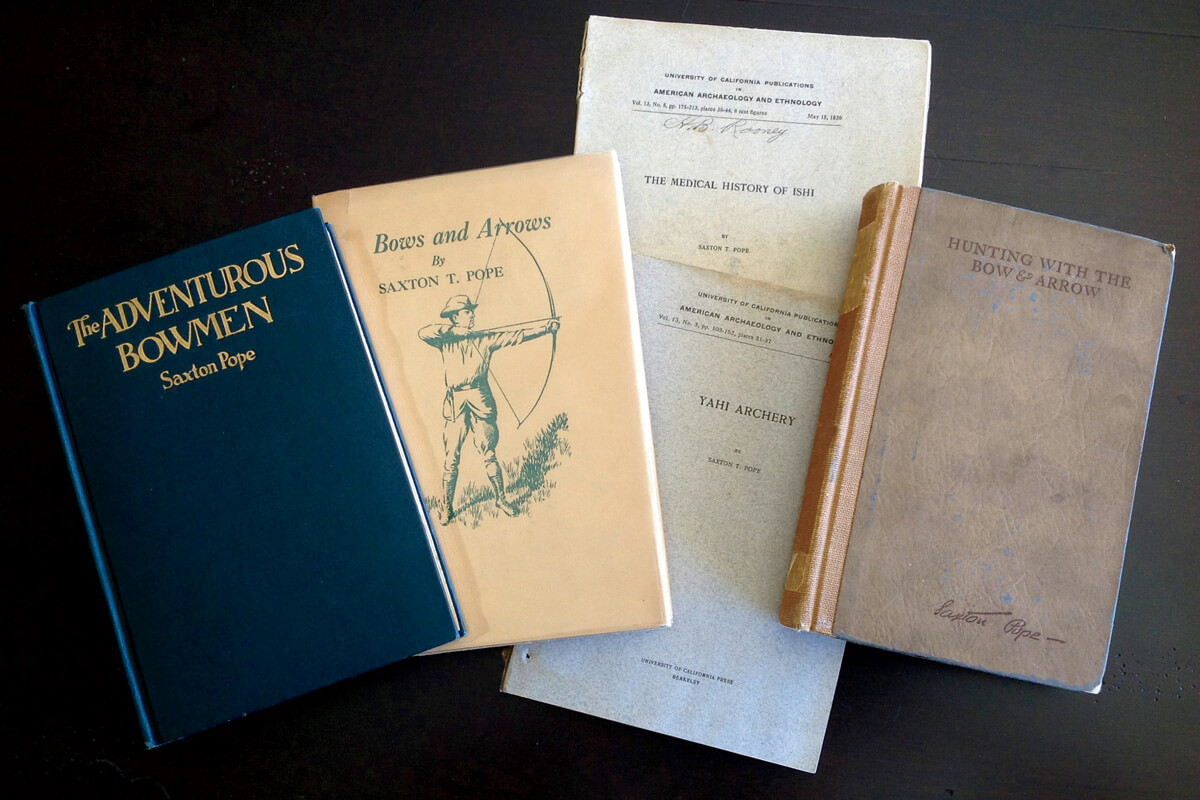

Classic bowhunting publications like the five written by Saxton Pope provide valuable insights to our sport’s history.

About 20 years ago, I was conducting archery seminars at a sports show in Northern California. Just before I went on stage, a gentleman walked up with a book in his hand. It was a leatherbound first edition of Saxton Pope’s 1923 classic, “Hunting With The Bow And Arrow.” The man opened the cover, and there was Pope’s original signature, plus a sheaf of yellowing papers that appeared to be arrow-testing notes handwritten by Pope himself.

I was shocked when this fellow told me he had found the book in a local pawn shop and purchased it for $10. He wanted to know what it was worth. I had a seminar to give, but I asked him to meet me after the presentation. My excitement faded when the fellow failed to show up. His find was surely a one-of-a-kind piece of bowhunting history discovered only a few miles from where Pope spent much of his adult life. I will always wonder where that book went, and for what price. I would have loved to own it myself.

In the years that followed, I managed to obtain first editions of all five books and pamphlets Saxton Pope wrote before his untimely death in 1926 at age 51. My copy of “Hunting With The Bow And Arrow” was also signed by Pope, but has no personal notes with it.

Bowhunting history is important. We all should know how this wonderful sport evolved. The late, great Fred Bear was one of my heroes, and arguably did more to promote archery hunting than any other single person. I had the good fortune to interview Fred at his original factory in Grayling, Michigan, about 15 years before his death. My personally autographed copy of “Fred Bear’s Field Notes” is dear to me because I spent time with the great man on several occasions.

A widely publicized estate auction in Squaw Valley, California, proved to be a bonanza for an archery history buff like me. Doug Walker was the late Publisher of “Western Bowhunter” and “National Bowhunter” magazines, plus a number of books. He collected many archery mementos during his long and storied career. In his early days as a sales rep for Bear Archery, Doug hunted and rubbed shoulders with famous early archers like Howard Hill and Fred Bear.

I traveled from Wyoming to California to attend that auction. My rental car was almost doing wheelies when I left.

Tucked in the backseat was Howard Hill’s famously inscribed “Little Sweetheart” hunting bow, and a hunting arrow signed by Hill. Howard gave both to Walker, along with photos to prove it. Fred Bear’s personally carried hunting knife set and compass were nestled beside the Hill items, and so was Art Young’s wooden-arrow transport box, made by his friend Saxton Pope before the duo hunted Africa in the 1920s. In that box were several Art Young arrows, including one with the broadhead Young commercially marketed after his Africa trip. In the bottom, scattered willy-nilly, were more than 100 Art Young broadhead blanks.

Perhaps the most near and dear to me from that auction is an obsidian arrowhead and obsidian knife given to Walker by Lee Pope — Saxton Pope’s son. Both were knapped for Pope by his friend Ishi during Ishi’s all-too-short stay at the University of California, where Pope worked as a physician.

I was born and grew up less than 20 miles from Ishi’s home territory in Northern California, which makes these artifacts precious to me. The “last wild Indian in America” was one of the forefathers of modern bowhunting.

Not many years ago, an antiquities expert in my home state of Wyoming obtained and advertised another Ishi arrowhead. A collector needs to be careful about fakes, but as was the case with Doug Walker’s items, this one checked out in spades. Charles Miles, a famous archaeologist, actually sat with Ishi in 1914 on the UC campus and watched Ishi knap this remarkably serrated head from milky white bottle glass. Miles was 20 years old and a university student at the time. He treasured this Ishi arrowhead for most of his life. It is featured in a photo on page 29 of his 1962 classic book, “Artifacts Of North America.” The authenticity of this arrowhead is reinforced by the fact that Miles never learned to knap arrowheads himself. There was no way he could have “manufactured” the piece.

An Ishi-knapped arrowhead from more than 100 years ago is special. But how about a stone knife aged at 1,000 years old?

Native American stone tools are abundant in North America, and legal to find and keep on private land in most states. I have discovered hundreds of flint, chert, and obsidian arrowheads in places where I’ve hunted and hiked, including in the heart of California’s Ishi Country. Before you look, please note that keeping artifacts found on public land is a violation of federal law.

Some of the best finds can be accidents, like the stone knife just mentioned. An unusually shaped point of stone appeared after a hard rain along a trench I had dug on my Wyoming property. Minutes later, after carefully removing more soil with my hands, I found myself holding a large knife blade fashioned centuries before. The notched tail indicated that a wood or bone haft (handle) once had been lashed to the knife. Based on the shape and size, one local expert aged my find at 1,000 to 2,000 years old. It gives me chills to hold it in my hand as an ancient hunter once did!

Other such happy accidents occur to lucky people. One guy I know found an old longbow at an antique mall in Cody, Wyoming. He knew just enough to be suspicious about what it really was. A careful analysis by an authenticating expert proved it to be one of Saxton Pope’s personal hunting bows; probably carried on Pope and Young’s grizzly bear hunt in Yellowstone Park in 1920.

Their guide was famous outfitter and outdoorsman Ned Frost, who lived in the Cody area. Nobody knows if this Pope bow was a memento kept for a while by Frost’s family, or if Pope left it behind for another reason. But Pope’s bow-making style was unique — from the way he shaped the limbs to the tight cord wrapping on the handle. This item is genuine.

You or I could only be so lucky!

In my mind, nothing beats bowhunting. But in the off-season, a stroll down memory lane with historical artifacts is pretty darn thrilling, too!

Finding Historical Artifacts

Archery artifacts are like gold — they are wherever you happen to find them. But if you wish to own a piece of bowhunting history, there are excellent ways to get on track.

Nice collectibles, including Fred Bear items, are regularly advertised online. As I write this, for example, a fairly low-number Fred Bear Signature Takedown Bow is being offered on eBay. Fewer than 300 of these consecutively numbered bows were produced in the 1980s before Mr. Bear passed away. Each was signed by Fred and features a flawless finish, 22-carat gold-plated hardware, and a handsome hardwood presentation case.

If you Google “archery collectibles” or similar phrases, you might be pleasantly surprised at what’s available.

Estate auctions and other auctions also can be good bets. One of the niftiest collectible auctions occurs at the biennial Pope and Young Awards Convention. I obtained my own Fred Bear Signature Bow in 2015 at the P&Y Convention Auction in Phoenix, Arizona.

Perhaps most special of all are accidental finds through pawn shops, antique stores, and the classified sections of newspapers. That’s not to mention abundant Native American artifacts that still show up on private land after rainstorms, floods, or freezing winter weather. Finding archery treasures is half the fun…enjoying them is equally satisfying.