Where Warm Waters Halt

By Del Shannon

(The following is written in a manner of ‘in my humble opinion’)

Where warm waters halt…

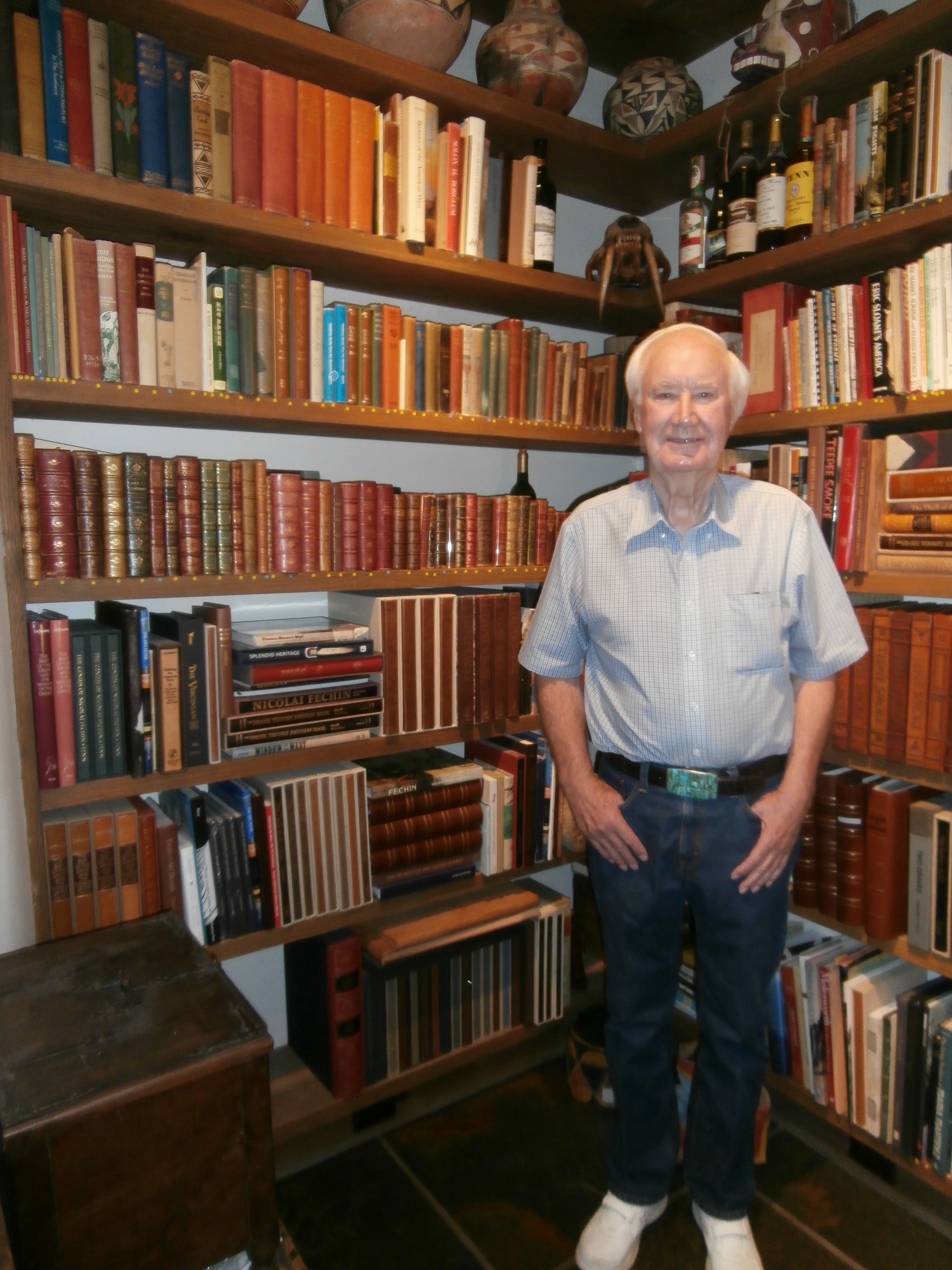

This is the now iconic first clue written by eccentric millionaire Forrest Fenn. He’s earned the “eccentric” title in spades because of a single act: About 7 years ago – nobody is exactly sure except Fenn himself – he stole into the mountains north of Santa Fe, New Mexico and hid a treasure chest filled with $2 million of gold, gems and other valuables. And in an act that can only be called defiant, he wrote a book and a poem that describes the route to get to the treasure and dared anyone to try and unlock the riddle and claim his cache.

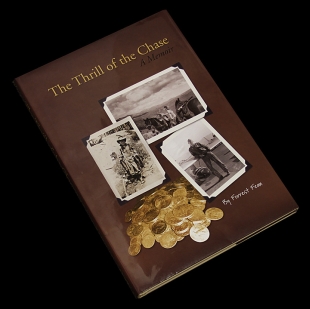

Since publication of Fenn’s The Thrill of the Chase in 2010, thousands of theories have been offered up as the location of this first clue. The location of the starting point of the hunt for Fenn’s treasure puts into context every other clue. Fenn has said you’re wasting your time if you’re searching without knowing where to start.

So where do warm waters halt? Not far from Questa, New Mexico.

I first heard about Forrest Fenn and his treasure chest while sitting in the breakfast area of the Taos Hampton Inn eating a self-made waffle and sipping coffee. I was there working on the reconstruction of the Cabresto Dam, just east of Questa. The Today show was on in the background and this is when I first saw Fenn, his piercing eyes revealing more intelligence than his carefully selected words. He was explaining that all you had to do was follow the nine clues spelled out in a simple poem and you were rich. Just like that, my curiosity was piqued.

Buying Fenn’s book and starting my search around Questa and Taos was obvious and easy. The land seemingly disappears into oblivion at the Rio Grande Gorge and thrusts to the heavens just steps away at the Sangre De Cristo Mountains, creating billions of hiding spots. Working in the area revealed that the landscape and its population are one and the same. The people of Questa and Taos stand out as easily as the canyons and peaks that surround them, none is even remotely like another.

Very little in the The Thrill of the Chase pointed me to anything that resembled the area around Questa and Taos. Fenn waxes Quixotic about his youth spent doing anything but focusing on school, holding a special place in his heart for Yellowstone.

One story in particular gnawed at me like an obsessive-compulsive beaver. In an early chapter titled “First Grade,” Fenn recounts being bullied by a boy named John Charles Whatever who often threatens to beat up Fenn, while at other times waves around a jar of olives in his face. The more I read and reread this passage the more it began to look like a ham at Chanukah – bizarrely out of place.

All I had to go on was the name “John Charles” and his olives, so I started there. After internet searches with dozens of permutations, I finally got lucky. After reading a history of Questa, once known as Rio Colorado, I learned that the great explorer, John Charles Fremont, once spent a few months during the winter of 1849 in Questa.

Fremont had tried to cross the southern Rocky Mountains in Colorado during the winter of 1848-49 and convinced 32 gullible men into joining his folly. Fremont was from an era where braggadocio was a suitable proxy for intelligence and thrived in an environment of delusional arrogance. By December 1848 eleven of his party had frozen to death and most others had started eating their belts. The party finally gave up and began limping their way south to New Mexico.

The surviving members stumbled into Questa in January 1849, but Fremont, sensing his men would be in an extended sour mood once they could again feel their feet and hands, headed for Taos. He was off to California a few weeks later

A tragic story, but this new knowledge didn’t appear to put me any closer to the Fenn’s treasure. John Charles Whatever’s olives did.

Besides being a lover of history, Fenn is a fly fisherman. The Red River fights its way out of the mountains near Questa, its last gauntlet is a maze of basalt boulders below a fish hatchery. Fed by springs, the water stays a consistent 48 degrees in the winter. In this same stretch of water there is a mid-winter (January through March) hatch of blue winged olive flies, which, along with the warmer water, coax brown trout out of the colder waters of the Rio Grande…along with the fishermen.

Fremont and his olives were pointing to Questa.

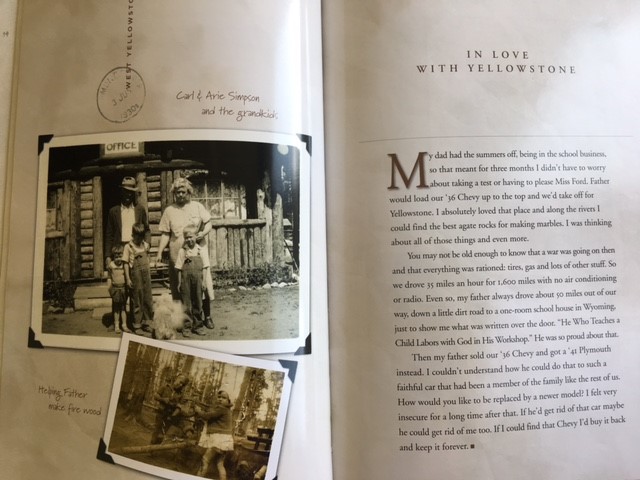

Still, more detail was needed, which came from another of Fenn’s stories. One evening, while re-reading the In Love With Yellowstone chapter I stopped after Forrest described his dismay after his father sold the families ’36 Chevy for a ’41 Plymouth. Why on earth was this such an important part of his life? And why didn’t he use the numbers ‘19’ in front of these dates. Every other reference to a year in The Thrill of the Chase uses all four digits – 1926 for example, the year his parents were married.

Forrest’s attempt at alarm over this car sale seemed insincere. After chewing on ’36 and ’41, which were details that seemed misplaced, and while using Google Earth to snoop around the Questa area, I noticed the latitude in the lower right hand corner. If I hovered the little electronic hand directly over the center of the village and it read 36 degrees, 42 minutes north. Hmmm… Then I moved it to the fish hatchery and it read – exactly – 36 degrees, 41 minutes, 0 seconds north. Holy crap!

Two hints at the starting place are compelling. If I could find a third it would concrete the location of “where warm water halt.” A local fly fisherman supplied my requested last hint.

Van Beacham is well known in Taos as the owner of the Solidary Angler, a local fly fishing shop and guide business. He’s also the author of A Flyfisher’s Guide to New Mexico, and this is how Van describes the Red River from the fish hatchery to its confluence with the Rio Grande in his book. “The lifeblood of the Rio Grande Gorge, the spring-fed section of the Red River extending from the hatchery downstream about 4 miles to the confluence with the Rio Grande is the main spawning tributary for browns and cutbows in the bigger river. It also provides major holding water for big cutbows and browns since the water stays about 48 degrees all winter long. Due to the warmer water temperatures, the Red River is the premier natural winter fishery in northern New Mexico.”

The Red River provides “holding water” for cutbow and brown trout because of its “warm water.”

It takes very little effort to connect the words “halt” and “hold.” In fact, they essentially mean the same thing. The word “hold” takes its origin, its etymology, from the Germanic word “halten,” which means “to hold.”

Bingo.

Warm waters halt in the Red River between the fish hatchery and its confluence with the Rio Grande. This is where anyone seriously searching for Fenn’s treasure must start.

Where to from there? Down river. Rio arriba.

In Fenn’s opening chapter titled “Important Literature” one of the books he talks about is For Whom the Bell Tolls. As with John Charles Whatever and his olives, if you look only at the surface you immediately reach a dead end, but when you dig a bit you realize there’s more to learn. Before Hemingway used the title for one of his books, For Whom the Bell Tolls was a line in a poem written by John Donne, a 16th century metaphysical poet. Donne begins with the famous first line of his poem, “No man is an island…” and ends with “…and therefore never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee.”

Follow the Rio Grande downstream from its confluence with the Red River and you eventually reach the John Dunn Bridge, named for the famous Taos gambler and entrepreneur Long John Dunn, an escaped convict from Texas who built the first bridge and toll road across the Rio Grande at this location. The splinters of Dunn’s original timber bridge are somewhere near El Paso, carried there by numerous spring floods, and in its place stands a steel truss bridge built by Taos County. Connecting John Donne and John Dunn was easy and obvious, especially after learning that both Dunn and Donne are different spellings of the Gaelic word for “brown.” And because Dunn and Donne are proper nouns, capitalize the ‘B’ and you have Brown. Voila.

But John Dunn’s home wasn’t at the bridge, it was in Taos just north of the plaza in the area now occupied by the John Dunn House Shops. How could the home of Brown be at the Dunn bridge if Dunn never lived there?

This problem was resolved by the author Max Evans and his book Long John Dunn of Taos. This homage to Dunn describes, among other things, his early 1900’s transportation company – really just several horses and a stagecoach – and how he met Taos visitors and artists at the nearest train depot in Servilleta, then the only way in or out of Taos. He piled them into his stage, headed east in a cloud of dust across the Taos plateau, and then snaked them into the Rio Grande Gorge via a harrowing and ridiculously steep switchback road.

Dunn built a stone hotel at the bottom of the gorge and on the edge of the Rio Grande where travelers were forced to spend the night, most of whom were grateful for the stop and for surviving the tormenting trip into the gorge, before delivering them to Taos the next morning. Dunn’s hotel was run by his mother, Susan Jane Dunn, who also lived at the site. A short rock wall on the east side of the river is all that’s left of Mrs. Dunn’s home, the home of Brown.

All of that is pretty convenient, but I still wanted more on Dunn. It turns out The Thrill of the Chase is almost overflowing with references to John Dunn. In the chapter “Looking for Lewis and Clark” Fenn talks about taking Babe Ruth candy bars with him when he and Donnie went into the mountains outside of Yellowstone for several days. The problem is the candy is actually called “Baby” Ruth bars. If you look into Babe Ruth you learn that a man named John Dunn (everyone called him Jack) signed Ruth to his first major league baseball contact. Hmm…

Or look at Fenn’s odd reference to Robert Redford in the “Important Literature” chapter. One of Redford’s most famous movie characters was The Sundance Kid (aka Harry Alonzo Longabaugh). In 1897, Longabaugh was arrested by Carbon County Montana Sheriff John Dunn after he and others from his gang robbed a bank in Red Lodge, MT. Wow!

Three separate John Dunn references in The Thrill of the Chase aren’t a coincidence.

The second clue – Put in below the home of Brown – points to the John Dunn Bridge. It’s too far to walk from where warm waters halt at the confluence of the Rio Grande and Red River; about 14 miles if you drive or eight-ish miles if you fight your way on foot down the Rio Grande. All these hints point to these locations as the first two clues.

But be wary from here. ‘Putting in’ could mean crossing the river or heading either up or down the canyon. And if you cross the river, which direction do you cross from? Do you head west or do you head east? You could go in three directions from the Dunn Bridge. I have my own ideas of where to head next, but not the chest, so they remain only ideas.

An obvious question remains: Why am I sharing this? It’s not as if I haven’t tried to find Fenn’s treasure on my own. I’ve made many trips to areas I felt certain that, when I walked out, I would be struggling to carry over 40 pounds of gold, jewelry and artifacts back to my car. But I’ve learned that the search isn’t as simple as my romantic visions make it out to be. It took a couple of years to unlock these first two clues and it may take much longer to unlock the rest.

And if I’m completely honest with myself, I’ll admit that I’d like the treasure found, in direct contrast to Fenn’s wishes that it be discovered 1,000 years from now. I’m a sucker for a good challenge wrapped in a mystery. So far I’ve done this alone, but I could be persuaded to work with someone else or as part of a larger group in the right circumstance. It’s always more fun to work with a team.

For the record, I didn’t contact Fenn for this story. What would he have said to me anyway? At best he would have complemented my sleuthing. More likely he would have just silently shrugged, smiled at me with his quick eyes, and walked away. I figure he’s done what he wanted to do and, whether or not he enjoys the attention he’s created, I’d make my own choice and leave him alone.

For the record, I didn’t contact Fenn for this story. What would he have said to me anyway? At best he would have complemented my sleuthing. More likely he would have just silently shrugged, smiled at me with his quick eyes, and walked away. I figure he’s done what he wanted to do and, whether or not he enjoys the attention he’s created, I’d make my own choice and leave him alone.

A final thought. To me, Fenn’s poem is a love letter to an area he unquestionably adores and which also helped him heal from his time in Vietnam. When you dig into the history of the Vietnam war, you learn that there is a Red River there too and pilots who flew into this maelstrom found some of the most dangerous air over this river.

I like to think that what Fenn found in New Mexico’s Red River was the thorough opposite of Vietnam’s. The paradox was not lost on him. In my mind I can see him casting for brown’s while marveling that one Red River could be filled to overflowing with death while the other held out its hand and reminded him there were still places where he could gently ease the visions of war from his head, replacing them with the rediscovered memories of the trout he chased in his youth as they led him, once again, to peace.

~by Del Shannon

.

If you would like to share your story or thoughts on MW, please send your submission to [email protected]!

Always Treasure the Adventure!

.