In 1784, a year and half after Congress adopted the Great Seal, Benjamin Franklin wrote a letter to his daughter in which he expressed his disapproval of the bald eagle — the national symbol.

While Franklin considered the eagle “a bird of bad moral character” that steals food from other birds, he called the wild turkey “a much more respectable bird” and “a bird of courage” that “would not hesitate to attack a grenadier of the British Guards who should presume to invade his farm yard.”

Franklin never made his opinion publicly known, but his enthusiasm for the turkey is now shared by millions of Americans who feast on the bird for Thanksgiving every year. The wild turkey has also become one of the country’s most popular game species, providing a number of socioeconomic benefits.

The return of wild turkeys

Today, five subspecies of wild turkey can be found across the continental United States and Hawaii. The subspecies that exists in North Carolina, the eastern wild turkey, ranges from southern Maine to northern Florida, west to eastern Texas and north to North Dakota.

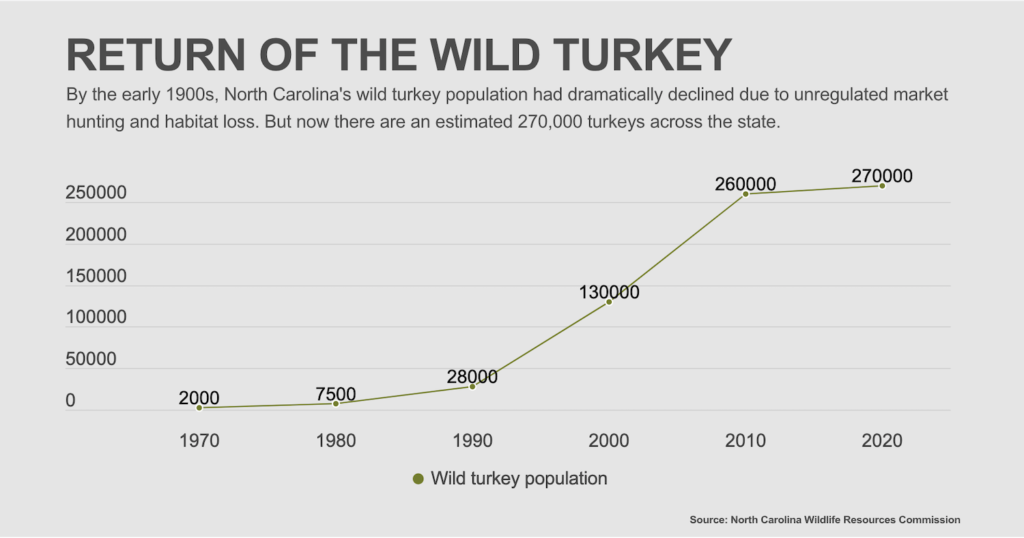

Wild turkeys were abundant in North Carolina when the first European settlers arrived. However, by the early 1900s, the state’s turkey population had dramatically declined due to unregulated market hunting and habitat loss caused by unsustainable logging and agricultural operations, according to Christopher Moorman, professor and interim associate head of the Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources at NC State’s College of Natural Resources.

Early restoration attempts began in the late 1920s with the release of pen-raised turkeys into the wild. Unfortunately, the birds weren’t accustomed to predators and extreme weather conditions. “It wasn’t long before they realized that pen-raised birds just couldn’t survive in the wild,” Moorman said.

In the 1950s, several years after the creation of the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, the agency initiated a “trap and transfer” program that involved live-trapping and relocating wild turkeys to areas where the bird had previously disappeared.

The agency also eventually made the controversial yet necessary decision to close the fall hunting season for wild turkey and to restrict the spring season to males only, protecting the females from harvest and allowing them to breed and grow the population.

By 2005, when the state’s “trap and transfer” program ended, wildlife biologists had relocated more than 6,000 wild turkeys to 358 restoration sites across North Carolina. About 1,800 of those birds were acquired from other states through the National Wild Turkey Federation Super Fund Program.

Moorman added that the adoption of sustainable land use practices also played an important role in the restoration of North Carolina’s wild turkey population.

Wild turkeys now exist in all 100 counties of North Carolina, with the latest figures showing an increase from an estimated 2,000 birds in 1970 to an estimated 270,000 birds in 2020.

A bird of many benefits

As a result of North Carolina’s restoration efforts and the increase in forests across the state, sportsmen are able to hunt wild turkey for five weeks during the spring each year.

“The wild turkey is one of North Carolina’s most popular game animals. It’s also one of the most difficult to hunt,” Moorman said. “Bagging one takes a lot of skill and patience, because wild turkeys have extremely good eyesight and are able to detect motion from far away.”

In each of the previous three hunting seasons, approximately 70,000 to 76,000 hunters pursued turkeys each spring, with an average of 14 to 15 days of hunting for each turkey killed. Only about 5% of hunters meet the state’s two-turkey bag limit; 16% take one turkey; and 79% go home empty handed.

Between April and May of this year, North Carolina hunters killed a record 23,341 wild turkeys. That’s nearly 5,000 more than the previous record of 18,919 harvested birds set in 2017.

Wildlife biologists with the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission said most of the increase in this year’s harvest is likely due to the “stay at home” orders issued in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, under which people had more time to hunt.

Hunting for wild turkey generates millions of dollars in tax revenues for the state and local communities through the purchase of licenses, firearms, ammunition and other related goods.

Moorman said hunting also serves as an integral part of American culture, providing a connection to the outdoors for millions of people. And most importantly, it creates public interest in wildlife conservation and promotes sustainable land management among landowners who allow hunting on their properties.

“A lot of the land in North Carolina is privately-owned,” Moorman said. “But hunting generates a bit of interest from landowners in habitat management, because they want to improve the conditions for wild turkeys and increase hunting access.”

In the Southeast, wild turkeys are highly adaptable and can survive in a variety of vegetation types. But they thrive best in landscapes with a mix of forest, cropland and fallow fields. The forests are used for cover, foraging and roosting, while the fields and other openings are used for foraging, mating and brood rearing.

“Turkeys have a single set of habitat requirements, which developed over eons of evolution. A variety of vegetation types, or land cover types, contribute to habitat that provides year round food and cover for turkeys,” Moorman said.

The science of gobbling

Wild turkeys are considered to be a prey and predator species, according to Moorman. Turkey eggs and hatchlings are a common food source for birds, reptiles and mammals, including snakes, hawks, owls, racoons, coyotes and bobcats. Adult birds also serve as prey to larger predators like bobcats.

Wild turkeys primarily feed on plant matter such as nuts, berries, acorns, grasses and seeds. But as predators, they will also eat insects and other small creatures like salamanders, snails and lizards.

“Turkeys are essentially avian vacuums when they move through the forest,” Moorman said. “They’ll eat just about anything that will fit in their mouths and won’t bite back.”

New challenges for wild turkeys

Despite its adaptability, the wild turkey has declined in a number of states across the Southeast over the past decade or so. In South Carolina, for example, the state’s turkey population has fallen from 176,000 birds in 2002 to 123,000 in 2019.

Some possible reasons for the decline include habitat loss, weather variation, disease and hunting. Indications are that one or more of these factors have caused a decrease in the number of young turkeys – also known as poults – that hatch and survive to adulthood, a measurement called the poult-per-hen ratio, according to Moorman.

Wild turkeys experience high mortality rates and are particularly vulnerable to predators during nesting and immediately after hatching. That’s why reproduction is essential for turkey populations to replace the individuals that don’t survive from year to year.

The breeding season begins in late March and early April, with hens typically laying a clutch of 10-12 eggs at the rate of about one egg per day. The eggs are incubated for 28 days beginning when the final egg is laid.

“Poults are able to run around and forage for themselves immediately after hatching,” Moorman said. “But they aren’t able to fly for the first 14 days. That’s when they’re most vulnerable to predation.”

North Carolina’s turkey productivity is currently stable with an estimated 2.2 poults per hen in 2019, the last year data is available. During the same year, poult survival was estimated to be four poults per brood – a collection of young turkeys from the same nest.

Moorman is currently working with Krishna Pacifici, an associate professor in the Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources, and researchers from the National Wild Turkey Federation and the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission to better understand when wild turkey nesting begins across the state’s three regions.”

The three-year study will also determine the success of turkey nests in each region and the potential causes of nest failure; document the vegetation conditions where turkeys nest in each region, helping direct habitat management to increase nesting over time; and estimate survival rates of female and male turkeys in each region and determine the primary causes of mortality.

Results from the study will ultimately help wildlife managers to better understand how North Carolina’s wild turkeys use their environment and will direct future management decisions, including the structuring of hunting seasons.

North Carolina’s spring turkey hunting season is structured around breeding and nesting activities to ensure sustainable harvests, according to Moorman. If hunting is allowed before each of these activities, it may negatively impact productivity. The study will help to ensure that the state’s turkey hunting season is appropriately timed.

Another major focus of the study is the prevalence of diseases in North Carolina’s turkey population and whether infected birds have lower survival or reproduction rates. Research shows that wild turkeys are susceptible to a number of diseases, including avian pox. This infectious, contagious viral disease accounts for nearly one quarter of the diagnoses of sick or dying wild turkeys in the Southeast.

To achieve the study’s objectives, Moorman and other researchers are capturing turkeys in each of the state’s regions and fitting them with radio-transmitters, tracking daily turkey movements and locating nests. The team located and assessed 106 nests just this year.