Reservoir flatheads present unique challenges and opportunities for anglers. These fish grow to gigantic proportions and yet go largely under-fished throughout much of the country. State records attest to massive flatheads that exist in lakes and reservoirs, including the 123-pound all-tackle record from Kansas’ 4,500-acre Elk City Reservoir.

What keeps many people from pursuing big reservoir flatheads is the unique mindset needed to catch them, requiring a different game plan than for river fish. In many respects, flatheads are more difficult to pattern in reservoirs. The lack of constant current means they generally aren’t homebodies, such as often is the case in rivers where they adhere to predictable current and cover locations. Instead, reservoir flatheads generally use a larger home range to meet their basic needs of food, shelter, and reproduction. For a better understanding of what it takes to be successful on reservoirs, Joe Shaw, one of the country’s more studious flathead anglers, offers a basic primer to set you on the right path to big stillwater flatheads.

Shaw has been fishing for as long as he’s been able to hold a rod. Since that time, he’s become a self-taught master of reservoir flatheads on impoundments in the central U.S., which largely go overlooked by flathead anglers in favor of traditional river settings. Shaw and his small crew of like-minded anglers have amassed impressive numbers of fish topping 40 pounds. They have landed plenty of fish topping 50 pounds and released several in the 60- to 65-pound range.

His early catfish pursuits were driven by his dad’s passion for chasing trophy channel cats throughout Ohio and beyond. After seeing photos of big flatheads in baitshops, they began setting out one livebait rod for flatheads during their channel cat outings. At around 11- or 12-years old, that livebait rod went down and he landed his first flathead—a 34-pounder.

Through trial and error, Shaw has refined his tactics. Over the years, he’s observed in general that reservoir flatheads grow more quickly than those in rivers within the same region. “We typically don’t see signs of spawning behavior, in the form of cuts, wounds, or scars, on fish below 25 pounds in the lakes we fish,” he says. “Faster growth rate and possible delayed spawning at an older age translates into larger 25- to 35-pound flatheads being the most common size encountered by our crew.” Today, he focuses on mature fish of 40 pounds or larger, and always has an eye toward a 70-pound record fish.

Most of his efforts are focused within a 6- to 7-hour drive in southern Ohio on mid-sized flood-control reservoirs ranging in size from 2,000 to 10,000 acres. These waters vary from small and shallow turbid systems, to ravine systems with plenty of deep water, vegetation, and good water clarity. The essence of Shaw’s program is the ability to approach different systems effectively regardless of their location or characteristics.

The timing of his flathead pursuits are limited to April through November. This time can be expanded in more southern locations and shortened in the North. Water temperatures in the mid-50s or more are an indicator of a good flathead bite in impoundments. Below this temperature range, the returns typically aren’t worth the effort. Understanding the annual cycles of flatheads is Shaw’s first key to success, as it helps to identify their location and general feeding behaviors.

Seasonal Breakdown

Winter to Early Spring—With water temperatures below 50°F, flatheads are generally inactive. Congregating in deep, stable water, they become lethargic and feed so infrequently that it’s not worth the effort to pursue them. Flatheads can be particularly vulnerable to foul-hooking during their winter lethargy, so Shaw doesn’t fish for them during this period. Knowing the location of wintering holes, however, can help decipher their early-spring and late-fall movements, as they transition from and to these wintering areas.

Shaw waits for the major spring warm-up when water temperatures quickly rise through the 60°F range and into the mid-70°F range before pursuing flatheads. He uses the preseason to do his homework on new fisheries and to analyze data and refine game plans on familiar waters. More on that in a bit.

Generally, April through May has Midsouth flatheads feeding in waters of 2- to 10-feet deep, depending on the depth characteristics of the reservoir. This shallow water warms quickly and holds most of the baitfish—shad, suckers, carp and panfish. Flatheads cruise these areas more often as stable warm water sets in. Sudden cold snaps send flatheads heading back toward wintering areas. Knowing their likely movement routes along depth contours can maximize your odds of contacting fish. Shaw equates the mindset needed for targeting reservoir flatheads to hunting whitetailed deer. It’s about studying maps and setting up on prime traveling and feeding routes to encounter them as they pass through.

Prespawn Feeding Binge—With water temperatures around 70°F, flatheads are in feeding mode as they ready for the spawn, spending more time close to spawning sites. With a fishery degree from Ohio State University, Shaw takes into consideration that flatheads are cavity spawners. As such, during this time period and into the Spawn Period, he directs his efforts on areas with dense wood, rockpiles, riprap shorelines, and bays with dense clusters of lily pad rhizomes.

When fishing ravine-type reservoirs, he generally fishes in 10 to 15 feet of water. In more turbid lakes, he may key on depths of 3 to 4 feet and set up on an hour or so before dark. Consider bays and creek arms that get plenty of sun exposure and that trap warmer surface water from prevailing winds. Since reservoir flatheads tend to move less frequently than river fish, it’s important to have confidence in your fishing spot and fish through the night.

Spawn and Postspawn—While Shaw hears many people complaining about the bite slowing during the spawn, he takes a positive spin. “Not all flatheads in a lake are spawning at the same time,” he says. “There are typically some fish in all three phases—prespawn, spawn, and postspawn—and they’re all holding in generally the same area. By identifying spawning sites, you can be on a consistent bite for an extended period. Plus, the postspawn bite can be intense, with skinny males able to eat everything they can fit into their mouths.”

During this time frame, with fish at all stages in the spawn, Shaw suggests varying bait size. He favors hardy livebaits that still have plenty of kick at the end of the night. Suckers and shad are ideal cold-water baits. As temperatures warm, consider bullheads, carp, goldfish, and panfish, depending on what’s legal where you fish.

Summer and Fall—The slowest and least predictable time for reservoir flatheads is August into September when fish are feeding less frequently and aren’t concentrated for a specific biological purpose. Look to deep rocks in the 20- to 30-foot range and intersecting creek channels to serve as holding areas for summer flatheads. Plenty of trial and error comes into play during the summer.

As fall sets in, the bite improves. The same locations that held fish in early spring produce in fall. Colder water means slower and less-aggressive fish taking larger meals. Up-size baits and be prepared to fish all night for a few good bites. As water temperatures cool into the 50s, the return on your efforts decrease.

With a general understanding of seasonal locations and behaviors of flatheads, formulating and implementing a successful game plan form the framework of Shaw’s fishing strategies.

Game Plans and Implementation

Get the best maps available for reservoirs that hold good numbers of flatheads in the size you intend to target. Shaw suggests working with a paper map to develop a plan. Color-code areas to correspond with seasonal locations of flatheads and likely migration routes used between seasons. Develop a fishing strategy based on your observations on paper, then go out on the lake for a full day and extensively scan areas of interest.

On the water, confirm or correct what’s shown on the map. Draw arrows on the map marking likely routes fish might use throughout the season. Place Xs where you plan to set baits and mark them with GPS icons on your electronics. Add key areas of cover not shown on the map and pay attention to the location, nature, and size of baitfish in the lake—clues to the type of bait you should be using and likely flathead feeding areas.

Time of year helps narrow down areas to fish. Shaw always has a Plan A and Plan B. Wind, boat traffic, fishing pressure, and displacement of baitfish are all variables that can keep you from fishing your Plan-A spots, so it’s important to have a backup plan. As part your planning, have good healthy bait available prior to the trip. Otherwise, plan one extra day to gather good bait on-site.

Preferred bait size can vary. “I’ve caught large flatheads on baits as small as 4 inches and on carp and suckers around 20 inches long,” he says. “Average bait size is in the 7- to 10-inch range and up to about a pound. I’ve experimented with baits up to around 24 inches or so, but hook placement and rigging become an issue with a bait that large,” he says.

Shaw suggests getting on the water at least an hour before sunset, as setting up in the dark can be difficult. He’s precise about bait placement and believes in sticking with a plan for the entire night and disturbing the area as little as possible.

He fishes from a G3 boat, which he typically beaches on the bank next to his desired fishing area, and also tows a kayak for setting baits. The kayak allows for precise placement of baits in areas beyond casting distance from the boat and eliminates any added trauma to the bait that casting can cause. He takes detailed notes on the positioning of each bait, and at times, uses a marker buoy as a point of reference to reset baits in the middle of the night.

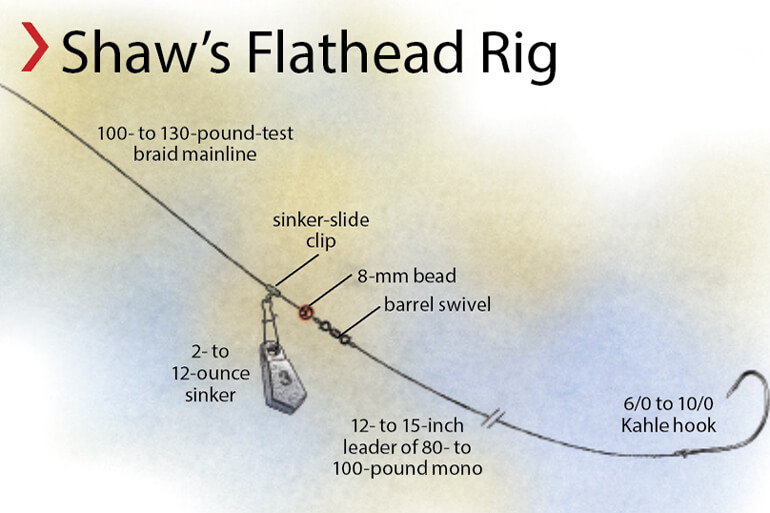

He describes his basic rig as a Carolina-style rig (slipsinker rig), with a Kahle hook (6/0 to 10/0, depending on bait size) on a 12- to 15-inch leader of 80- to 100-pound abrasion resistant monofilament tied to a barrel swivel.

“Above the swivel on 100- to 130-pound braid mainline, I run an 8-mm bead, then a plastic sinker slider that allows me to quickly change sinkers or add weight needed for a lively or large bait,” he says.

“I prefer a Kahle hook because in most stillwater reservoirs, flatheads won’t always move away from you after eating a bait. They often meander around or even swim straight toward you. This reduces the effectiveness of circle hooks. Kahle hooks are more likely to embed in the corner of their mouths more often than J- or octopus-style hooks.

“I use sinkers weights from 2 to 12 ounces, depending on bait size. The heavy leader and mainline are needed to withstand the abuse of a large flathead that might run 75 to 100 yards as it swims back and forth, potentially dragging the line through cover. One-hundred- to 130-pound-test braid sinks, making it easier to manage on long drops as opposed to 65- to 80-pound braids that float and can create tangles with other lines if they go slack. All of this is trial and error. I’ve had flatheads damage and break everything smaller than what I’ve described, and with opportunities at big fish as precious as they are, I try to sway the odds in my favor.”

Getting to the lake early before it gets dark helps prevent spooking fish. Stick with your plan. Some of Shaw’s best nights for big fish have taken place when he didn’t get his first bite or land his first fish until 4 a.m. and then had multiple big fish prior to sun-up. Flatheads are predators and there is no way to know exactly when they’re going to begin their feeding movements on any given night.

The biggest mistakes he sees by newcomers to lake fishing is arriving too late to a spot and not being precise in their bait placement or giving up on a spot after a couple hours and then trying to set up on a second spot in the dark. When fishing trophy fish, the hope is to get one or two bites per night by big fish and catching at least one of them. Changing locations throughout the night and being imprecise with bait placement rarely nets positive results.

Taking Notes

As with any fishing log, keep track of water and air temperature, wind and weather conditions, barometric pressure, moon phase, baitfish movement, bait used, bait that got bites, bait that didn’t get bites, and more. Negative results can be just as valuable as positive results.

Any spot that you’ve mapped with confidence should be fished at least 2 to 3 nights prior to ruling it out. Good note taking helps you replicate successes. Try to master one reservoir closer to home prior to applying that experience to more distant fisheries.

Shaw’s program provides anglers with the fundamental principles to master reservoir flatheads anywhere across the country. As you master these fisheries, remember to be good stewards of the resources.

*In-Fisherman Field Editor Steve Ryan contributes to all In-Fisherman publications. He’s an outstanding multispecies angler, pursuing trophy fish near and far.