Butchering a rabbit is a bit harder than cutting up a chicken. In fact, that reason — along with a higher feed-to-meat ratio, is why America became a nation of chicken-eaters and not rabbit-eaters, a question actually in doubt a century ago.

Most of the rabbits and hares Holly and I eat are wild cottontails or jackrabbits, although an occasional snowshoe hare or domestic rabbit finds its way to our table. And it’s a domestic I decided to work with for this tutorial. They are all built the same.

Incidentally, when you are finished portioning out your rabbit, take a look at my collection of rabbit recipes. I am betting you’ll find a recipe you like there!

Why butcher your own rabbits? They’re cheaper, sometimes a full $1.50 a pound less than a pre-portioned bunny. Also, if you are raising your own or are a hunter, this is good information to know.

First you need a very sharp knife: I use a Global flexible boning knife, but a paring knife or a fillet knife would also work, as would a chef’s knife. I also use a Wusthof cleaver and a pair of kitchen shears. Have a clean towel handy to wipe your hands, and a bowl for trimmings.

Start by slicing off any silverskin and sinew from the outside of the carcass, mostly on the outside of the saddle.

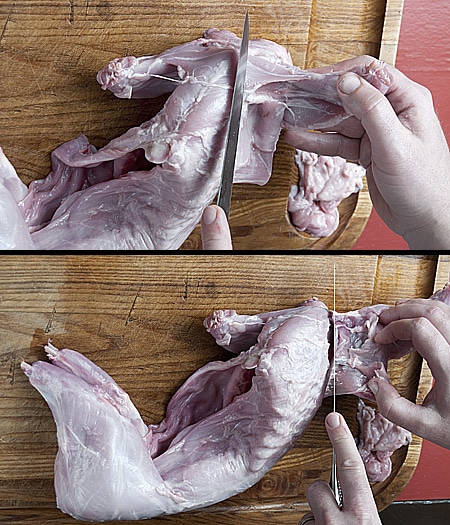

I always start cutting up a rabbit by removing the front legs, which are not attached to the body by bone. Slide your knife up from underneath, along the ribs, and slice through.

Usually there is some schmutz (a technical term) attached to the front leg that does not look like good eats: fat, sinew, and general non-meaty stuff. All can go into pate if you are so inclined. Or you can toss it.

Next comes the belly. A lot of people ignore this part, but if you think about it, it’s rabbit bacon! And who doesn’t like bacon? In practice, this belly flap becomes a lovely boneless bit in whatever dish you are making. Also good in pate or rillettes.

Turn Mr. Bunny over and slice right along the line where the saddle (or loin) starts, then run the knife along that edge to the ribs. When you get to the ribcage, you fillet the meat off the ribs, as far as you can go, which is usually where the front leg used to be. Finish by trimming more schmutz off the edge; if you’re using this part for pate or rillettes, leave the schmutz on.

Up next, the hind legs, which is the money cut in a rabbit. Hunters take note: Aim far forward on a rabbit, because even if you shoot up the loin, you really want the hind legs clean — they can be a full 40 percent of a gutted carcass’ weight.

Start on the underside and slice gently along the pelvis bones until you get to the ball-and-socket joint. When you do, grasp either end firmly and bend it back to pop the joint. Then slice around the back leg with your knife to free it from the carcass.

Once you’ve done both legs, you are left with the loin. It’s really the rabbit loin vs. chicken breast thing that did it in for the bunny as a major meat animal — there’s a larger swath of boneless meat in a chicken than in a rabbit. Both have a tendency to dry out, but then there’s that delicious chicken skin…

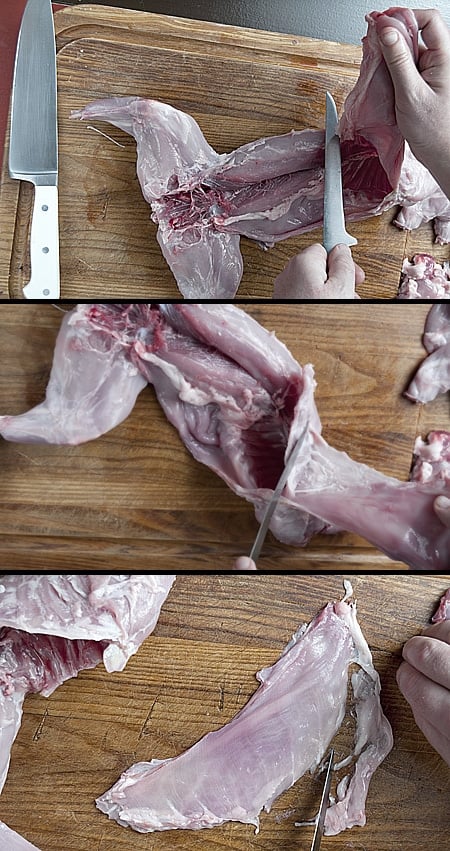

Now is a good time to remove a little more silverskin. The back of the loin has several layers, and most need to be removed. The final layer is very tough to cut off, and I often leave it. On a large hare or jackrabbit, however, this layer needs to go, too. Again, this stuff can be ground and used in pate.

You’re now ready to portion the saddle. Ever heard the expression “long in the saddle?” It is an animal husbandry term: A longer stretch of saddle or loin means more high-dollar cuts come slaughter time. And meat rabbits have been bred to have a very long saddle compared to wild cottontails.

Start by removing the pelvis, which is really best in the stockpot. I do this by taking my cleaver severing the spine by banging the cleaver down with the meat of my palm. I then bend the whole shebang backwards and finish the cut with the boning knife. Or you could use stout kitchen shears.

Now you grab your kitchen shears and snip off the ribs, right at the line where the meat of the loin starts. The ribs go into the stockpot, too.

Guess what? There’s more silverskin to slice off. Could you do it all in one fell swoop? You bet, but it is delicate work and I like to break it up to keep my mental edge: The reason for all this delicate work is because the loin is softer than the silverskin, and if you cook it with the skin on, it will contract and push the loin meat out either side. Ugly. And besides, if you are making Kentucky Fried Rabbit, who wants to eat sinew?

Your last step is to chop the loin into serving pieces. I do this by using my boning knife to slice a guide line through to the spine. Then I give the spine a whack with the cleaver or I snip it with kitchen shears.

And voila! A bunny cut into lots of delicious serving pieces.

What about the offal, you say? I’ll do more on that later, but suffice to say rabbit livers and hearts are pretty much like those of a chicken. The kidneys are delicious, too. Remove the fat (rabbit fat tends to be foul-tasting) and peel the nearly-invisible membrane off the kidney before cooking.

What to do with your newly portioned rabbit? Well, you could browse through my rabbit recipes, as I mentioned above, but my favorite recipe is buttermilk fried rabbit. With an ice cold beer, it is every bit as good as it looks!