A few key tools, especially a good blade, and quick adjustments will get you dropping catfish fillets into the fryer in no time. (Shutterstock image)

Some fish are pretty easy to clean. Walleyes, perch, crappies—no problem. Others prove a little more challenging.

Take filleting a channel catfish, for instance. Not only do you have to contend with spines and a bony head, you’ve also got fish slime. Loads of it.

However, just because something seems difficult, it doesn’t mean it is. If you’re looking to transform your freshly caught cat into the guest of honor at your next summer fish fry, you can easily do so. All you need are the proper tools, the patience to take your time and the know-how to get the job done.

TOOL TIME

A well-stocked catfish cleaning arsenal consists of four things: a quality knife, a set of side-cutting pliers, a sharpener and a single Kevlar glove. My go-to knife is an 8-inch Dexter blade. The Sani-Safe handle offers a positive grip while the carbon steel holds a sure edge. I also keep an old-school 7.5-inch birch-handled Rapala knife as a backup. With any knife, you’re looking for the right combination of backbone and flexibility.

You can also go the electric route. Occasionally, I’ll switch to a 7.5-inch Rapala corded electric knife, which I run off a 1,000-watt Honda generator when I’m away from home. There’s a learning curve with an electric blade, but once you get the feel for it, filleting is a breeze.

Beyond knives, you want a good set of side cutters for clipping the spines prior to filleting. If you’re using a manual knife, a sharpener is also crucial. I like a Firestone two-stage sharpener to periodically touch up blades. Last but not least, wear a Kevlar glove on your off hand to protect against accidental cuts and pokes.

CULINARY CONCERNS

This qualifies as a personal choice, but I’ve generally found the best-eating channel cats—or any catfish, really—to be those in the 1- to 4-pound range. Any smaller, and there’s not much there. Any bigger—especially those caught in warm summer water—and they tend to get a bit strong and mushy.

Throughout much of the Midwest, channel cat limits are quite liberal. Blue and flathead catfish limits are a little more conservative in some places, but typically still pretty generous. Regardless, these limits translate to plenty of fish for anyone, so it’s both easy and wise to release larger cats to replenish the supply.

Step 1

Clip the one dorsal and two pectoral spines as close to the body as possible. Some anglers skip this step, which is fine. However, I always do it to lessen chances of getting punctured during cleaning. For those unfamiliar with the event, there are few things as painful and slow to heal as a catfish “poke.” If you do get poked, rub a bit of the fish’s slime—actually a protective mucus covering—into the wound. It can work wonders, both relieving the pain and speeding up healing.

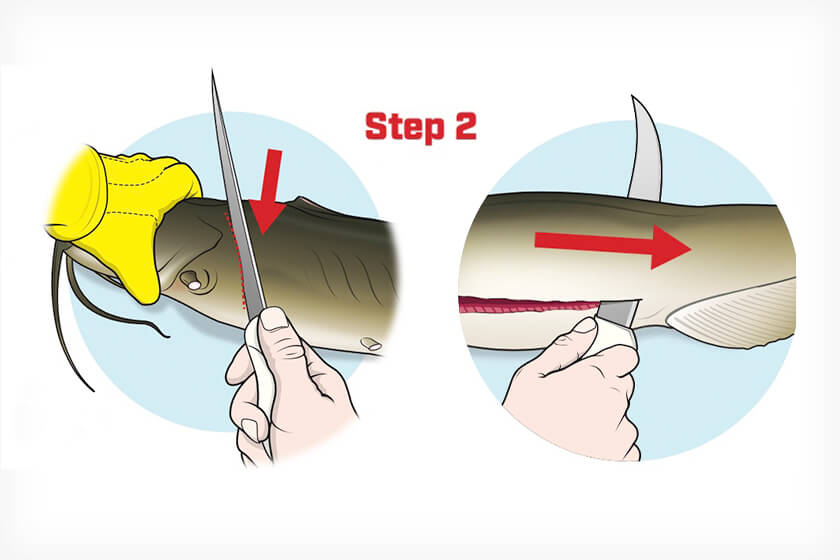

Step 2

I’m a righty and prefer to work left to right, so what I’m about to describe will reflect that. Your style may differ, of course.

With the fish on its side, head to the left and gloved hand firmly on it, begin with a downward (vertical) diagonal incision at the tip of the V-shaped bone directly behind the gill cover.

The bone is easy to see and even easier to feel. With steady pressure, cut down to the spine, turn your wrist 90 degrees counterclockwise and proceed to cut toward the tail. Efficiency here involves maintaining contact with the spine and allowing the knife to do the work. Don’t saw; just use a smooth, steady motion and stop about an inch or so before completely severing the fillet.

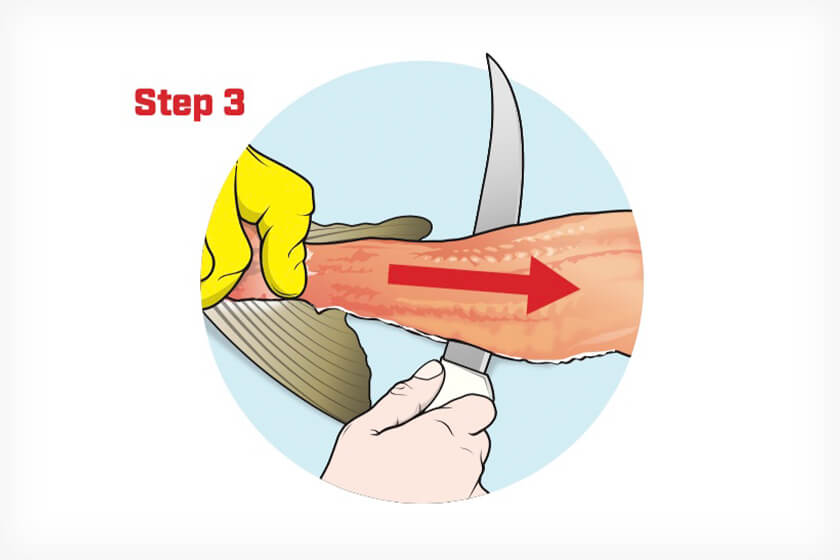

Step 3

Without removing the knife from the fish, use the thick edge of the blade to flip the still-attached fillet over onto the work surface—that is, skin down and flesh up. Starting at the point where the fillet is attached to the carcass, slip the blade under the flesh and work—again smoothly—toward what was the head section of the cat. A good, sharp blade should flow easily, with only minor stutters at the intact rib bones.

Step 4

Finally, with the interior of the now-skinless fillet facing upward, use an angled blade approach to trim the entire rib cage (bones) away from the flesh. It might sound complicated, but it’s not. Slip the mid-section of the blade edge under the rib bones and let it glide toward the belly.

Repeat these steps for the other fillet. Then, rinse each fillet and drop them into a bowl of ice water to toughen them for five to 10 minutes. Next comes the most enjoyable part of the entire process: dinner.