Having the right tools makes all the difference when sharpening your hunting knife. (Photo courtesy of Jonathan Hanson)

When I finally learned how to properly sharpen a knife, I then had to decide what sharpening system was best for my newfound skills. And there are a lot of knife sharpeners on the market to choose from: spinning-stone gadgets, at-home on the kitchen counter devices and one-handed wonders worth throwing in a hunting pack. But I was looking for a kit that would put the best edge on my blade without gimmicks. After doing my research, I found these five are the best knife sharpeners for hunters.

Japanese Water Stones

The connoisseur’s choice? Or the Luddite’s? Either and both. Modern sharpening systems that automatically control the sharpening angle have been a boon to consumers, and it’s difficult to deny that they can extend blade life by reducing the amount of material removed. And yet humans have been satisfactorily sharpening knives on rocks for millennia. No result from a fancy contraption gives me quite the satisfaction I get producing a scalpel-like edge on a set of Japanese water stones. Practically speaking, there’s no wondering whether a blade will be too small, too big, or too thick or thin when using stones—you can sharpen anything from a straight razor to an axe. The generous surface area accommodates the largest butcher knife in one stroke.

$40-$90 | sharpeningsupplies.com

As the name implies, water stones are designed to be immersed in water for 20 to 30 minutes before use; this opens any clogged pores in the stone, lubricates it, and prevents clogging during use, especially if you splash the stone frequently. (Never, ever use oil on a water stone.) Japanese grit grades are slightly different than American grades, but in general, 150 to 200 is coarse, 400 to 800 is medium, 1,000 to 2,000 is fine, and above that (some go to a glass-like 8,000) is ultra-fine. You could get by with a single, 1,000-grit water stone, but a good set comprises a 600, a 1,000, and a 2,000, plus a flattening stone. Some sort of stone holder is very helpful; this can be as simple as a homemade plywood bracket, but I prefer a sink bridge—an adjustable frame that holds the stone securely over your kitchen sink or a basin, eliminating puddles on the counter.

Lansky

Arthur Lansky Levine pioneered the controlled-angle sharpening system in 1979 and revolutionized knife sharpening for tens of thousands of users. The Lansky comprises a simple blade clamp with right-angle ears drilled for sharpening angles from 17 to 30 degrees. The stones—three to five, depending on the kit—clamp to rods that ride in the selected hole. That’s all there is to it, but the increase in precision over freehand sharpening was a revelation.

$40-$115 | lansky.com

Forty years later, the newest Lansky kit is essentially identical to the first one (in fact I simply photographed my 30-year-old example), proving the cleverness of Levine’s original vision. There’s no really comfortable way to grip the Lansky, although you can brace it against the edge of a workbench. The stones are just four inches long, limiting the available stroke length—for long kitchen knives, I have to reposition the clamp to cover the entire blade. The plastic stone holders have finger indentations, but if one were really careless a fingertip could conceivably stray over the edge of the stone, with sanguinary consequences. Nevertheless, the Lansky still does a fine job, and with a starting kit priced at just $40, the Lansky is the most affordable system in this roundup. It’s also the most portable, with everything, including a bottle of oil, fitting inside a case the size of an old VHS tape. I recommend the $58 Deluxe 5-stone system, which includes grits all the way down to 1,000.

Edge Pro Apex 4

Ben Dale wanted a fast and effective manual system for his commercial sharpening route, so he made his own prototype. Then another, and another. After 100 prototypes and 100,000 knives sharpened, he introduced the Edge Pro—a system so superior that friends and I who own them use it as a verb: “Bring your knife over; I’ll Edge-Pro it for you.”

The Edge Pro comprises a tripod base that can be planted on a countertop with its suction cups, or clamped to a workbench with an optional attachment. A vertical rod with colored angle marks (which I wish were noted in degrees instead) holds a sliding attachment through which the guide rod/stone holder glides smoothly. The stones are a generous six inches long, allowing a blade-length sweeping stroke, and the configuration of the ball grip means it would be nearly impossible to get a finger between the stone and the knife.

$255 | edgeproinc.com

The Edge Pro has no blade clamp. Instead, the user holds the knife against the guide shelf while applying the stone with the other. This means that when you switch sides of the blade, you also must switch hands for each task. It also requires a bit of divided attention to ensure you’re holding the knife solidly while employing the stone correctly. But the results are astonishing, and astonishingly quick. Setting up the system takes longer than most sharpening tasks, so I make sure to do batches—including those from a widening circle of friends. Loosening and retightening one wing nut is all it takes to change the angle from chef’s knife thin to bushcraft-knife stout. The only issue I’ve ever had with the Edge Pro is with very small pocket knives, the edges of which can be blocked by the guide clip.

Edge Pro offers models from $165 up to $700 professional systems. I think the $255 Apex 4 is the best compromise in content and capability, and it remains my go-to sharpener when I don’t feel like getting my Zen on with the water stones.

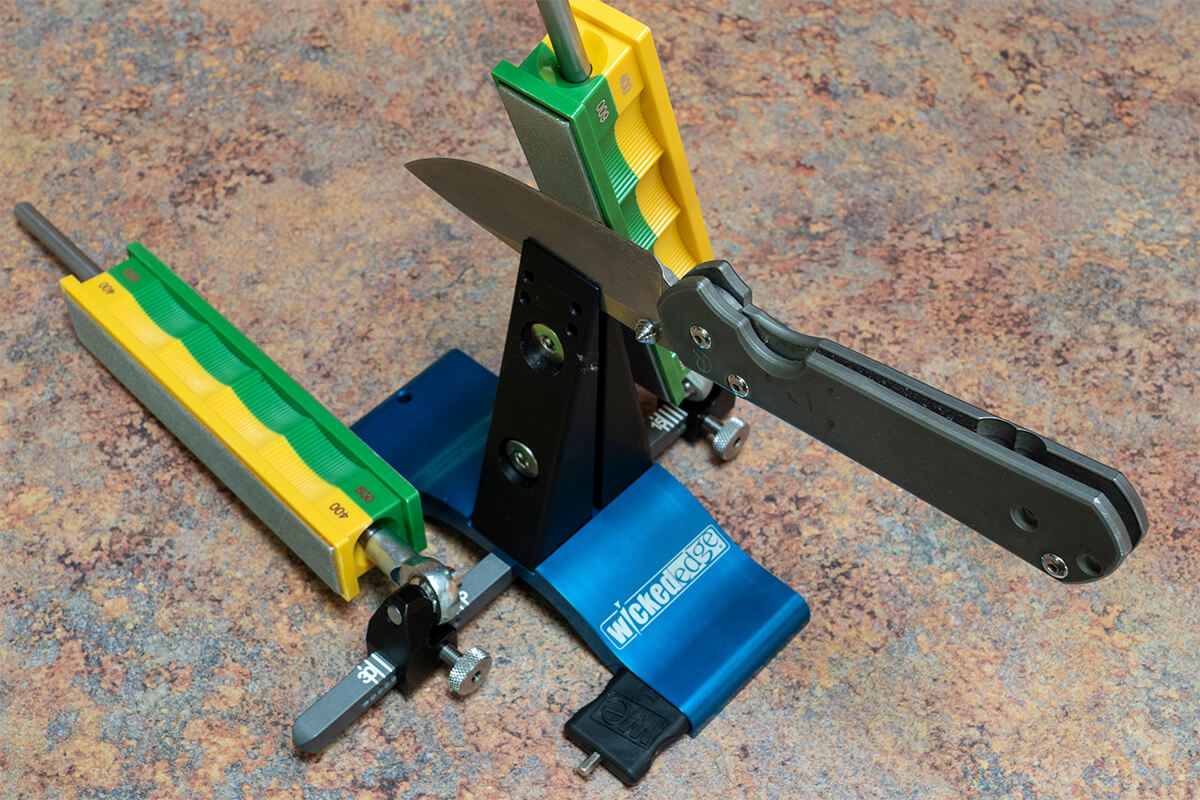

Wicked Edge WE100

Where do you go after Edge Pro sharp? How about Wicked Edge sharp? The Wicked Edge system overcomes a couple of drawbacks of the Edge Pro. First, the blade is held firmly in a pyramidal tower bolted to the base, leaving you one free hand you don’t get with the Edge Pro and ensuring the blade remains in the proper orientation. Second, the Wicked Edge incorporates a guide rod on each side of the blade, and paired sets of diamond stones, so there’s no swapping the knife around to work on each side. Use one stone and guide rod to raise a burr on one side, then simply switch to the other stone and guide rod. And each stone is reversible and incorporates two grits, so to step from 100 to 200 grit you simply swivel the stone on the rod. Exceptionally convenient. The rods adjust securely and easily to nearly infinite edge angles between 15 and 30 degrees. The ball socket at the bottom affords silky-smooth action.

$350 | wickededgeusa.com

However, I found a couple of issues with the Wicked Edge. First, although the stones are a reasonable 5.5 inches in length, they bottomed out on the rod on all my hunting knives well before reaching the end, reducing the effective stroke to no more than that of the Lansky. Worse, there is no stop when you lift the stone on the rod each time to begin a new stroke, and if you aren’t paying close attention you can raise the bottom edge of the stone above the edge of your blade and catch it on the end, a disconcerting feeling.

A more serious failure involves the stone selection. The WE100 only comes with four grits of diamond stones—100, 200, 400, and 600. This is fine for rough work profiling a new edge, but, despite the company’s claim, is completely inadequate to put a decent finished edge on a blade; the 600-grit stones leave scoring easily visible to the naked eye, even after I broke them in on a couple of my less expensive knives, as advised. The 800/1000 stones that are the minimum needed to properly finish an edge will cost you an extra $80, and if you want a really superior polish, the 1,500/2,000 grit stone set is an additional $99, turning a $350 sharpening kit into a $529 kit. Even the $575 WE130 only comes with the 600-grit stones. I would have been much more impressed with this system if it had included an adequate stone selection.

Worksharp Ken Onion Edition Knife and Tool Sharpener

Why only one electric sharpener here, and a weird one at that? Because the electric sharpeners I’ve tried that use the standard rotating ceramic stones, while convenient, are usually intended for kitchen knives, and are not adjustable for more robust blade angles. Some I’ve used make it easy to remove too much material if you’re not careful—and some simply don’t get knives very sharp.

The Worksharp—designed with input from legendary knifemaker Ken Onion—is different. It uses tiny, .75-inch-wide abrasive belts of varying coarseness, easily switchable. And the blade angle is adjustable between 15 and 30 degrees. Plus the Worksharp will also sharpen serrated knives, scissors—even axes, by removing the knife blade guide.

$150 | worksharptools.com

Once you choose your first abrasive belt—from coarse to fine, depending on whether you’re profiling a new edge or touching up an existing one—you set the blade guide angle to match your edge, and hold the machine down with one hand while powering it with that hand’s index finger. With your other hand you draw the knife slowly across the belt, alternating side as you raise a burr. It takes some practice to do this consistently as you must concentrate to keep the blade against the guide. Also, the instructions caution you to turn off the machine each time you reach the tip of the blade, to avoid rounding it off.

I was able to achieve a superb edge with the Worksharp after some practice. However, it is the machine’s most highlighted characteristic that gives me pause. Because the abrasive belt is flexible, as you press the knife against it the belt produces a slightly convex—rather than flat—profile. Worksharp claims this produces a more durable edge, and I have no reason to doubt that. The problem is that you’re then locked into using only the Worksharp to sharpen your blade. A stone or any of the other systems here will flatten the convex edge, and in doing so will necessarily remove more material than if the blade had a flat bevel to begin with.

On the other hand, a convex bevel is exactly what you want on an axe, and the Workshop did a splendid job on my Gränsfors Bruk forest Axe. So, it’s either an excellent $150 axe sharpener, or an excellent knife sharpener to which you must dedicate your blades? Or both.