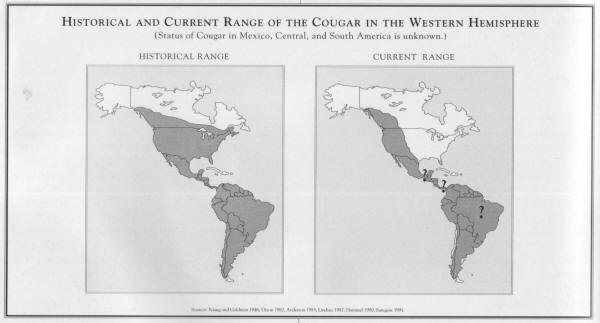

Cougars were roaming the Americas when humans crossed the Bering land bridge from Asia 40,000 years ago. They watched the Spanish conquer the Aztecs and the pilgrims land at Plymouth Rock. The big cats prowled the banks of the Mississippi, Colorado, and Amazon rivers. They crossed the high, windy passes of the Sierra Nevada, the Rocky Mountains, and the Andes. They witnessed the first Mormons arrive in Utah, prospectors invade the California gold fields, and gauchos herd cattle in Argentina’s pampas. From the Canadian Yukon to the Straits of Magellan – over 110 degrees latitude – and from the Atlantic to the Pacific, the cougar once laid claim to the most extensive range of any land mammal in the Western Hemisphere. (1)

That cougars can be found from sea level to 14,765 feet, (2) and survive in the dense forests of the Pacific Northwest, the desert Southwest, and Florida’s Everglades, is testimony to the big cat’s resilience and adaptability. These qualities were put to the test as never before when European explorers set foot in the Americas in the 14th century. Early colonists viewed the lion as a threat to livestock, as a competitor for the New World’s abundant game, and most importantly, as the personification of the savage and godless wilderness they meant to cleanse and civilize. Their death sentence pronounced, cougars were hunted, trapped, and shot on sight, and their habitat was stripped away as land was cleared to make way for agriculture and new towns. Today, the lion’s known range in North America has been reduced to areas in the 12 western states, the Canadian provinces of British Columbia and Alberta, and a small remnant population in southern Florida. An increasing frequency of sightings suggest that some populations may still survive in parts of the eastern United States and Canada. (3)

The cougar is listed in dictionaries under more names than any other animal in the world

THE CAT OF MANY NAMES Because of their enormous range, cougars are known as “the cat of many names.” Writer Claude T. Barnes listed 18 native South American, and 25 native North American, and 40 English names. (4)

The cougar is listed in dictionaries under more names than any other animal in the world.. (5) The Guarani Indians of Brazil called them cuguacuarana, which French naturalist Georges Buffon corrupted into cougar.. (6,7) Puma comes from Quichua, an Inca language, meaning “a powerful animal.”. (6,8) To the Cherokee of the southeastern United States the big cat was Klandagi, “Lord of the Forest,” while the Chickasaws called him Koe-Ishto, or Ko-Icto, the “Cat of God.”. (7) In Mexico they are leopardo, to other Spanish-Americans, el Leon.. (6,7)

In 1500, Amerigo Vespucci was the first white man to sight and record a cougar in the Western Hemisphere. Vespucci, after whom the two American continents are named, was probing the coastline of Nicaragua when he saw what he described to be lions, probably because of their similarity to the more familiar African lion. (8,9) Two years later, on his fourth voyage to the New World, Christopher Columbus saw “lions” along the beaches of what are now Honduras and Nicaragua. (6,7,8) The honor of being the first European to sight a “lion” in North America fell to Alvar Nunez Caheza de Vaca, who in 1513, saw one near the Florida Everglades. (8)

Tyger was another name used for the American lion throughout the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida during the 15th and 16th centuries. (7) Today, cougar, mountain lion, and puma are the most common names used in the western United Stares, while panther, painter, and catamount are more frequently heard east of the Mississippi. Panther is the Greek word for leopard; painter is an American colloquial term for panther; and catamount is a New England expression, meaning “cat-of-the-mountains.”(10) Biologists call it Felis concolor, literally, “cat of one color.” Throughout this book, the names cougar, mountain lion, puma, and panther are used interchangeably.

Tyger was another name used for the American lion throughout the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida during the 15th and 16th centuries. (7) Today, cougar, mountain lion, and puma are the most common names used in the western United Stares, while panther, painter, and catamount are more frequently heard east of the Mississippi. Panther is the Greek word for leopard; painter is an American colloquial term for panther; and catamount is a New England expression, meaning “cat-of-the-mountains.”(10) Biologists call it Felis concolor, literally, “cat of one color.” Throughout this book, the names cougar, mountain lion, puma, and panther are used interchangeably.

FROM WHENCE CAME CATS? The fossil record of felines is as filled with mystery as today’s cats themselves. Paleontologists and biologists have traditionally relied upon fossils and differences in physical structure of modem animals to map the evolution of a particular species. This has proven difficult with cats for two reasons: most ancestral cats occupied tropical forests, where the conditions for the preservation of fossils is poor; and most of the physical characteristics of cats are related to the capture of prey, with the result that all felines are very similar in structure. (11) As a result, no less than five different hypotheses have been offered to explain the relationships between the various groups and subgroups of extinct and modern cats. (12)

While there are differing interpretations of the evolution of the cat family (Felidae), a few facts are agreed upon. Modern and extinct carnivores have a common ancestor called Miacids. These primitive, tree-dwelling carnivores lived in the forests of the Northern Hemisphere 39 to 60 million years ago. Then, about 40 million years ago, a burst of evolution and diversification produced the modern families of carnivores. These new carnivores fall into two major groups: a bear-like group (arctoids), consisting of modem bears, seals, dogs, raccoons, pandas, badgers, skunks, weasels, and their relatives; and a cat-like group (aeluroids), a lineage including the cats, hyenas (yes, that’s right), genets, civets, and mongooses. (12)

The first cat-like carnivores to appear were the saber- tooth cats, about 35 million years ago. (11) The sabertooths became extinct about 10,000 years ago worldwide, at the end of the last glaciation. (13) While the sabertooths met their demise, however, the modem cats were evolving and diversifying. Ancestral pumas lived in North America from three to one million years ago, with modern pumas appearing about 100,000 years ago or less. (11) The American lion had arrived.

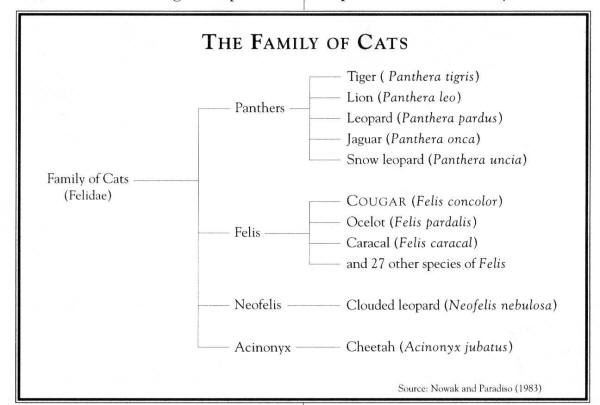

THE FAMILY OF CATS Just as there is disagreement about where cats came from, there is debate over how to classify the 37 species of cats that exist today. I discovered no less than six different proposed classification systems for Felidae during the research for this book. The Latin name Felis concolor was first given to the cougar in 1771 by Carolus Linneaus, the father of taxonomy. (It was Linneaus who devised the binomial system for describing and classifying plants and animals.)

Today, scientists generally divide the cat family (Felidae) into two groups, or genera: Panthera, the large roaring cats, and Felis, the smaller purring cats.. (11) The ability to roar depends on the structure of the hyoid bone, to which the muscles of the trachea (windpipe) and larynx (voicebox) are attached. The tiger (Panthera tigris), African lion (Panthera leo), leopard (Panrhera pardus), and jaguar (Panthera onca) represent this group. Members of Felis possess the ability to purr or make shrill, higher-pitched sounds. Of the seven cat species in North America, only the jaguar (Panther onca) belongs to Panthera. The other six – cougar (Felis concolor), lynx (Lynx canadensis), bobcat (Lynx rufus), matav (Felis wiedii), ocelot (Felis pardalis), and jaguarundi (Felis yagouaroundi) – are purring cats and are members of Felis.. (14) The cougar is the largest of the purring cats.

Today, scientists generally divide the cat family (Felidae) into two groups, or genera: Panthera, the large roaring cats, and Felis, the smaller purring cats.. (11) The ability to roar depends on the structure of the hyoid bone, to which the muscles of the trachea (windpipe) and larynx (voicebox) are attached. The tiger (Panthera tigris), African lion (Panthera leo), leopard (Panrhera pardus), and jaguar (Panthera onca) represent this group. Members of Felis possess the ability to purr or make shrill, higher-pitched sounds. Of the seven cat species in North America, only the jaguar (Panther onca) belongs to Panthera. The other six – cougar (Felis concolor), lynx (Lynx canadensis), bobcat (Lynx rufus), matav (Felis wiedii), ocelot (Felis pardalis), and jaguarundi (Felis yagouaroundi) – are purring cats and are members of Felis.. (14) The cougar is the largest of the purring cats.

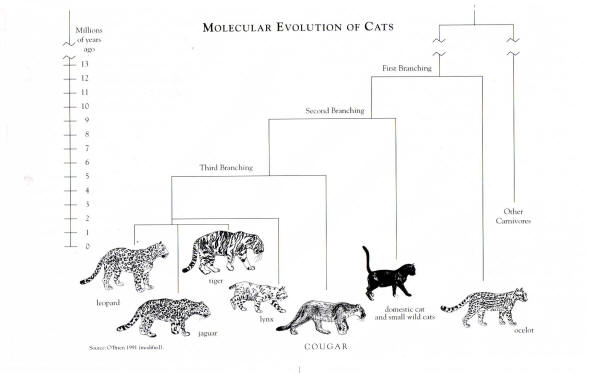

A different approach to the evolutionary and taxonomic puzzle of feline classification was taken recently through the application of the new science of molecular evolution. By examining the rate of change of the genes in the DNA molecules of different cat species. biologist Stephen J. O’Brien and his colleagues revealed that the 37 species of modern cats evolved in three distinct lines. The earliest branch occurred 12 million years ago and includes the seven species of small South American cats (ocelot, jaguarundi, and others). The second branching took place 8 to 20 million years ago and included the domestic cat and five close relatives (Pallas’s cat, sand cat, and others). About 4 to 6 million years ago a third branch split and gave rise to the middle-sized and large cats. The most recent split (1.8 to 3.8 million years ago) divided the lynxes and the large cats. This third line gave rise to 24 of the 37 species of living cats, including the cougar, cheetah, and all big cats. (15)

The differences of these two classification systems are apparent and are representative of the disagreement among experts. Some biologists believe we have progressed as far as we can in our understanding of feline taxonomy through the examination of museum specimens, and that future answers lie in the study of behavior, ecology, and genetics.. (16) For instance, a cheetah-like cat existed in North America less than a million years ago, but was extinct by the end of the Pleistocene era (10,000 years ago). It evolved in parallel with the modern African cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) and was similar in appearance; however, it appears to have been more closely related to the living cougar than to the cheetah.. (11,13) Resolving where cougars fit into the cat family would give us one more piece of the puzzle of how the American lion came to be.

The differences of these two classification systems are apparent and are representative of the disagreement among experts. Some biologists believe we have progressed as far as we can in our understanding of feline taxonomy through the examination of museum specimens, and that future answers lie in the study of behavior, ecology, and genetics.. (16) For instance, a cheetah-like cat existed in North America less than a million years ago, but was extinct by the end of the Pleistocene era (10,000 years ago). It evolved in parallel with the modern African cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) and was similar in appearance; however, it appears to have been more closely related to the living cougar than to the cheetah.. (11,13) Resolving where cougars fit into the cat family would give us one more piece of the puzzle of how the American lion came to be.

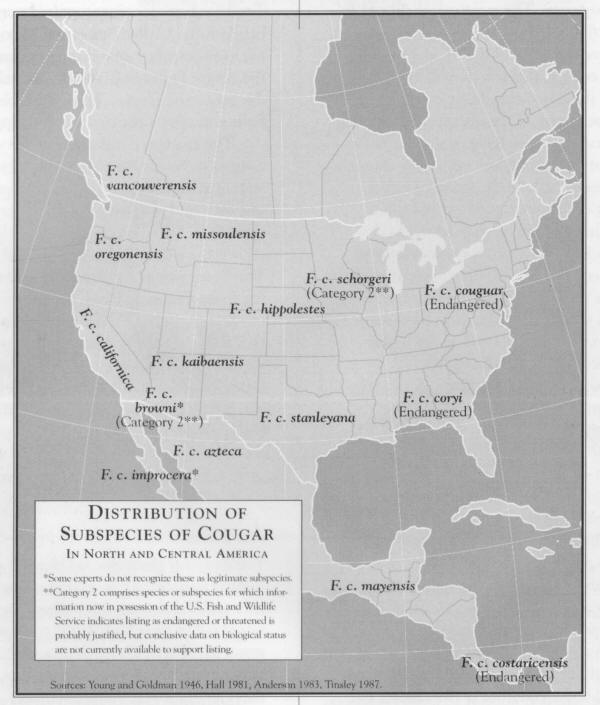

SUBSPECIES AND STATUS When a species is as broadly distributed as the cougar, regional variations in physical appearance occur. For instance, mountain lions from Alberta look somewhat different than the Florida panther, a fact that relates to the different geographic habitats in which the lion lives. (17) Wildlife taxonomists recognize these regional variations by dividing Felis concolor into some 26 subspecies or geographic races, scattered across North and South America. (18) This is similar to the different races or breeds of the domestic dog. Edward A. Goldman, coauthor of the classic, The Puma: Mysterious American Cat, explains how the subspecies of cougar are classified: “The subspecies or geographic races of the puma, like those of other animals, are based on combinations of characters, including size, color, and details of cranial [skull] and dental structure(6) Twelve subspecies are recognized north of the border between the United States and Mexico. (6,7,18) (When writing the scientific name of a particular subspecies, such as the cougar found in Colorado, the subspecies name follows the genus and species. Thus, the Colorado cougar becomes Felis concolor hippolestes or F. c. hippolestes.)

The existence and status of the various subspecies of cougars in North America is the subject of heated debate among academics and wildlife professionals.

The existence and status of the various subspecies of cougars in North America is the subject of heated debate among academics and wildlife professionals. The two subspecies found in eastern North America, the eastern panther (Felis concolor couguar) and the Florida panther (F. c. coryi), are classified as endangered and fully protected. (19) The Yuma puma (F. c. browni), a subspecies found along the lower Colorado River, is currently a candidate for listing as endangered. (20) While cougar populations are considered to be healthy in many parts of western North America, populations adjacent to rapidly expanding urban areas are facing critical habitat loss. In southern California for example, mountain lions in the Santa Monica Mountains and Santa Ana Mountains are fast losing ground to rampant residential development.

APPEARANCE AND SIZE The cougar is plain-colored like the African lion, but is of slighter build with a head that is smaller in proportion to its body. Male pumas do not have the distinctive mane and tufted tail of their Old World cousins. (2) The absence of a mane led to an early myth about mountain lions: Early Dutch traders in New York were puzzled that the lion skins they obtained were those of females Only. They questioned Indian hunters and were assured that such animals existed, but only in the most inaccessible mountainous places, where it would be foolhardy to attempt to hunt them. (1)

Except for the smaller jaguarondi of Central and South Americas, the cougar is the only plain-colored cat in the Americas. (2) The sides of the muzzle and the backs of the ears are dark brown or black, while the chin, upper lip, chest, and belly are creamy white. (21) Atop the small head sit a pair of short, rounded ears. The cougar’s long and heavy tail is perhaps its most distinctive feature. Measuring almost two-thirds the length of the head and body, it is tipped with brown and black. Cougars are the largest native North American cat except for the slightly larger jaguar (Panthera onca), which is occasionally found in the southwestern United States. (22) The sexes look alike, though males are 30 to 40 percent larger than females. (23) The largest animals are found in the northern and southern extremes of its range. Though sizes vary greatly throughout the cat’s geographic range, a typical adult male will weigh 110 to 180 pounds and the female 80 to 130 pounds. Exceptional individuals have exceeded 200 pounds, but this is rare. Males will measure 6 to 8 feet from nose to tail tip and females 5 to 7 feet. (2)

Cougars are the largest native North American cat except for the slightly larger jaguar (Panthera onca), which is occasionally found in the southwestern United States. (22) The sexes look alike, though males are 30 to 40 percent larger than females. (23) The largest animals are found in the northern and southern extremes of its range. Though sizes vary greatly throughout the cat’s geographic range, a typical adult male will weigh 110 to 180 pounds and the female 80 to 130 pounds. Exceptional individuals have exceeded 200 pounds, but this is rare. Males will measure 6 to 8 feet from nose to tail tip and females 5 to 7 feet. (2)

In captivity, cougars have lived as long as 21 years. (24) In the wild, the cats probably live only half as long. Lack of a reliable way to determine a mountain lion’s age makes exact measurements difficult. In the wild, a 10-year-old lion is likely a very old cat. Experts also disagree over which gender lives longer on the average. Some think the added stress of raising kittens guarantees female lions a shorter life. The lifespan of both sexes in hunted populations is probably shorter. (25) But, even in the absence of hunting, a short life span is to he expected of a predator that faces the frequent hazards of feeding on prey much larger than itself.

Cougar The American Lion Line Illustrations Copyright (1992-2009) by Linnea Fronce

CHAPTER NOTES

- Seidensticker J.C. 1991a. Pumas. Pages 130-138 in J. Seidensticker and S. Lumpkins, eds. Great Cats: Majestic creatures of the wild. Rodale Press. Emmaus, Pennsylvania.

- Sunquist, F. C. 1991. The Living Cats. Pages 28-53 in J. Seidensticker and S. Lumpkins, eds. Great Cats: Majestic creatures of the wild. Rodale Press. Emmaus, Pennsylvania.

- Morse, S. C. 1991. Forest Ecologist and Wildlife Habitat Consultant. Morse and Morse Forestry. Jericho, Vermont. (Personal communication)

- Barnes, C. T. 1960. The cougar or mountain lion. Ralton Co., Salt Lake City.

- Lynch, W. 1989. The elusive cougar. Canadian Geographic August/September: 24-31.

- Young, S. P., and E. A. Goldman. 1946. The Puma: Mysterious American Cat. American Wildlife Institute, Washington D. C.

- Tinsley, J. B. 1987. The puma: Legendary lion of the Americas. Texas Western Press, The University of Texas at El Paso.</st1:placetypew:st=”on”>

- McMullen, J. P. 1984. Cry of the panther: Quest for a species. Pineapple Press, Englewood Florida.

- Guggisberg, C. A. W. 1975. Wild cats of the world. Taplinger Publishing Co., New York.

- Hornocker, M. G. 1969b. Stalking the mountain lion – to save him. National Geographic November: 638-655.

- Kitchener, A. 1991. The natural history of wild cats. Cornell University Press. Ithaca, New York.

- Neff, N. A. 1991. The cats and how they came to be. Pages 14-23 in J. Seidensticker and S. Lumpkins, eds. Great Cats: Majestic creatures of the wild. Rodale Press. Emmaus, Pennsylvania.

- Van Valkenburgh, B. 1991. Cats in communities: Past and present. Page 16 in J. Seidensticker and S. Lumpkins, eds. Great Cats: Majestic creatures of the wild. Rodale Press. Emmaus, Pennsylvania.

- Hornocker, M. G., C. Jonkel, and L. D. Mech. 1979. Family felidae. Mountain lion (Felis concolor). Wild Animals of North America. National Geographic, Washington, D.C.

- O’Brien, S. J. 1991. Molecular evolution of cats. Page 18 in J. Seidensticker and S. Lumpkins, eds. Great Cats: Majestic creatures of the wild. Rodale Press. Emmaus, Pennsylvania.

- Seidensticker, J. C. 1991b. Introduction to “The Living cats” by F. C. Sunquist. Page 28 in J. Seidensticker and S. Lumpkins, eds. Great Cats: Majestic creatures of the wild. Rodale Press. Emmaus, Pennsylvania.

- Shaw, H. 1989. Soul among lions. Johnson Books. Boulder, Colorado.

- Anderson, A. E. 1983. A critical review of literature on puma (Felis concolor). Colorado Division of Wildlife. Special report Number 54.

- U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1991. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants, 50 CFR 17.11 & 17.12 July 15, 1991. U. S. Government Printing Office: 1991-296-520:50024. Washington D. C.

- Duke, R., R. Klinger, R. Hopkins, and M. Kutilek. 1987 Yuma puma (Felis concolor browni). Feasibility Report Population Status Survey. 22 September 1987. Harvey and Stanley Associates, Inc. Alviso, California. Completed for the Bureau of Reclamation.

- Currier, M. J. P. 1983. Felis concolor. Mammalian Species No. 200, pp 1-7. American Society of Mammalogists.

- Lindzey, F. 1987. Mountain lion. Pages 656-668 in M. Novak, J. A. Baker, M. E. Obbard, and B. Malloch, eds. Wild furbearing management and conservation in North America. Ministry of Natural resources, Ontario, Canada.

- Quigley, H. 1990. The complete cougar. Wildlife Conservation March/April: 67.

- Collette, M. 1991. Founder and President, Wildlife Waystation, Angeles National Forest, California. (Personal communication)

- Hopkins, R. A. 1991. Wildlife Biologist, H. T. Harvey and Associates. Alviso, California. (Personal communication)

![Air gun 101: The differences between .177 & .22 – Which jobs they do best ? [Infographic]](https://airgunmaniac.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/g44-218x150.jpg)