“Here they come again!” Two ducks were already down in the water, and the 25-or-so remaining members of the flock had circled back and were zooming toward our blind again. I was in no position to shoot, but Holly was. BOOM! One shot, and one more ruddy duck fell from the flock.

Our eighth of the hunt. We ended the day at Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area with nearly a full strap of diver ducks: Two spoonies, two canvasbacks, and the eight ruddy ducks. Duck hunters reading this are probably harrumphing right now: Good on ya for the cans, but spoonies? Ruddies? What a bunch of garbage ducks!

I have to admit that even I wasn’t overly thrilled about shooting so many ruddy ducks. Spoonies to me are a known quantity. They have a deservedly bad reputation as table fare in every region of California except for ours. In rice country, spoonies eat more rice and fewer shrimpy things or algae, making them taste far better here than anywhere else. Ruddies, on the other hand, are true diver ducks and are known eaters of clams, fish and other animal bits — all of which make them taste like low tide on a hot day.

Or so I’d thought. I don’t shoot the little ruddy ducks very often because I’ve lumped them in mentally with our other little diver duck, the bufflehead. And I distinctly remember my last roasted bufflehead: Fishy, bloody and dark — assertive, in a three-day-old mackerel sort of way. Ew.

Yet here we were with a bunch of ruddies. They’re too small to use for sausage — a large drake weighs only 1.4 pounds — so they’re best roasted whole, like teal. But if they tasted anything like that bufflehead, I was not looking forward to this. Then I remembered that my friend Matt had basically shot nothing but ruddies when he taught himself to hunt ducks at Yolo several years ago. He seemed to think they were fine.

So I consulted the Duck Bible, Frank Bellrose’s Ducks, Geese and Swans of North America. Every serious aficionado of waterfowl needs this book, as it covers the biology of every duck, goose, swan or whatnot that inhabits our marshes. What makes it especially important for my purposes is that it includes an entry on the food habits of each species. Remember, you are what you eat.

Also remember that in general, humans consider the meat of birds who eat mostly plants to be tastier than that of birds who eat mostly animals. Fish-eaters are at the bottom of the list. What, then, do ruddies eat?

Plants, I was shocked to learn. “Ruddy ducks are primarily vegetarians,” Bellrose writes. Only about a quarter of their food comes from animals, mostly midge larvae and not clams or snails (it’s the bufflehead who’s inordinately fond of snails). Sago pondweed, bulrush seeds and wigeon grass are their primary diet. When we cleaned our ruddies, their crops were full of bulrush seeds, not clams.

That made me feel a lot better, especially after going through the trouble to pluck these birds; diver ducks are far harder to get out of the feathers than are puddle ducks like mallards; the feathers are denser and are more tightly attached to the skin. As I was working my fingers raw plucking these little ducks, I’d also recalled that ruddies showed up on market lists from a century ago. Were ruddies a market duck?

A little more research found that the answer was not “yes,” but “hell, yes!”

Check this out: These are retail market prices for ducks taken from the Currituck Sound in North Carolina in 1884:

- Pair of Canvasbacks: $1.00-2.75 ( $64.83 )

- Pair of Redheads: $0.50-1.60 ( $37.72 )

- Pair of Ruddy ducks: $0.25-0.90 ( $21.22 )

- Canada Goose: $0.50 ( $11.79 )

The price in parentheses is the modern price, adjusted for inflation. Astounding, isn’t it? Also, note that no other species of waterfowl are listed. Then I found a 1901 restaurant menu cited in Appetite City: A Culinary History of New York from a place called Rector’s that listed restaurant prices for a single cooked wild duck:

- canvasback, $4 ( $101.79 )

- redhead, $3 ( $76.34 )

- mallard, $2.50 ( $63.62 )

- ruddy duck, $2 ( $50.89 )

- teal, $1.25 ( $31.81 )

Can you imagine plunking down a Benjamin for one duck? Even crazier, can you imagine paying more than $50 for a ruddy, which barely feeds one person? I was gobsmacked.

You’ll note that the vaunted pintail, universally considered the finest-tasting duck nowadays, doesn’t even make the cut. And when pintails do show up in market lists, they are always cheaper than ruddy ducks. What was going on here? Back to the literature, and what emerged was a picture of an age when diver ducks, not puddle ducks, were king at the table.

Adolphe Meyers, in his “Post Graduate Cookery Book” (1903), wrote that “many connoisseurs and epicureans prefer the ruddy duck to the redhead, claiming that it equals the canvasback in flavor. This bird has become scarce in late years, and its price went up in consequence.”

In the 1900 book “I go A-Marketing,” Henrietta Sowle writes: Another duck of delectable flavor is the ruddy duck or broadbill as it is known in some localities…”

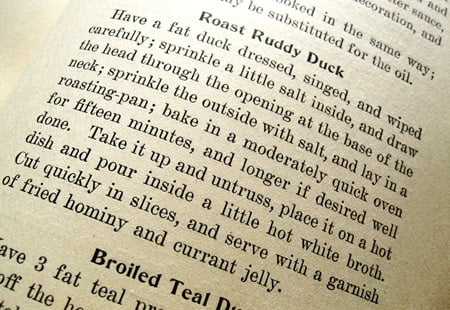

Ruddy duck appears in all sorts of cookbooks from the mid-1800s to 1918, when market hunting was officially banned in the North America. This recipe is from my 1903 edition of Lily Haxworth Wallace’s “The Modern Cookbook and Household Recipes”:

So how did the ruddy duck fall from grace? How did this duck, considered third only behind the mighty canvasback and the regal redhead, get tossed into the trash duck heap with fish-eaters like mergansers or goldeneyes?

No one seems to know. But I can guess. There is another “Duck Bible” out there, J.C. Phillips’ A Natural History of the Ducks, written in 1926 — nearly a decade after market hunting ended. Phillips’ words echo everything I’ve heard said about the ruddy, both in modern literature and from pretty much every other hunter I’ve ever spoken with:

“Its intimate habits, its stupidity, its curious nesting customs and ludicrous courtship performance place it in a niche by itself… Everything about this bird is interesting to the naturalist, but almost nothing about it is interesting to the sportsman.”

Except flavor, it seems.

I decided to roast our ruddies as simply as I could, using my standard roast duck recipe, which is nothing more than salt, a little fat or oil, and a very hot oven. If a duck is going to taste “off,” we’ll know with this method, which hides nothing. So, after 15 minutes in a “quick” oven — 500 degrees, to be exact — this is what the little ruddy looked like:

Crazy, eh? It’s like an orb of duck. I can’t pin it down for certain, but it appears that the origin of the term “butterball” is neither a turkey nor a bufflehead, but a ruddy duck. Ruddy ducks are an odd species all by themselves, oxyura rubida, not that closely related to mallards or even canvasbacks. It shows in the bone structure, which is stocky to the extreme.

So how did Mr. Ruddy taste? Wonderful, I am happy to report. Seven of our eight ducks were pretty fat, so I pricked the skin with a needle to help it render out. That melted duck fat mixed with the fleur de sel I sprinkled over the birds to make a perfect sauce — not fishy tasting in the slightest.

The meat is striking, a lurid scarlet, even when cooked to medium. It is a bluer shade of red than other divers, and is far darker than mallards, gadwall or pintails. The wings are inedible cooked this way, but the legs were chewy but tasty. How to describe the taste? Strong — this time in a good way — dense, extremely juicy and with an aroma that screams wild bird.

Bottom line? Ruddies are not for civilians accustomed to wan domestic ducks. It’s an eater’s duck, a duck with character and flair. It had every reason to stand with the canvasback and redhead as the royalty of the waterfowl world, and has every right to retake that position among modern hunters — if they’re willing to give this little butterball a chance.