The state has such a diversity of habitats and weather patterns that one part may experience a gobbler bumper crop while another may suffer a silent spring. (Photo by Ron Sinfelt)

During the 2018 spring season, North Carolina’s turkey hunters saw a big drop in the harvest from the previous season’s all-time record. Will this year’s season rebound set another record, or have gobbler numbers reached their peak? Read on to find out.

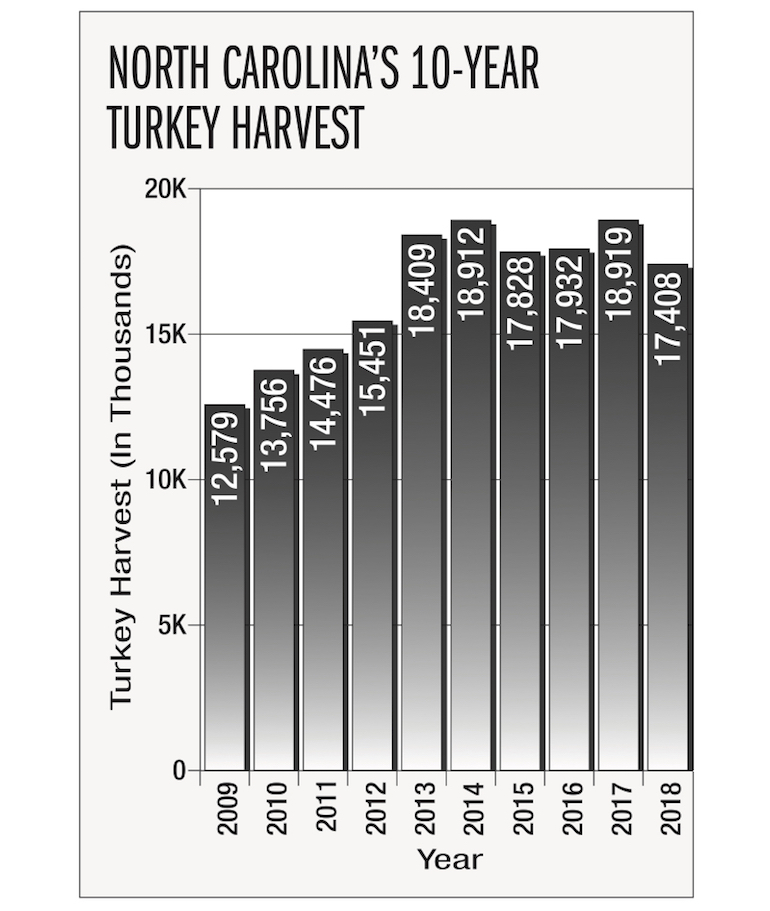

During the 2018 spring turkey season, North Carolina’s 60,000 turkey hunters reported harvesting 17,408 birds. That number is 8 percent below the record harvest of 18,819 birds, set in 2017.

While that sounds ominous, when viewed from another perspective, it was also not far off from the 2016 harvest of 17,932 birds. A trend has developed, with the harvest chugging along at around 18,000 birds since it exceeded that number for the first time in 2013. Has the turkey population reached its potential, with the harvest bumping up and down near all-time highs? Was last season’s decline an anomaly due to some factor that resulted in a temporary lowering of the harvest such as poor recruitment or bad weather that kept hunters out of the woods?

These are good questions. However, the answers can be as elusive as a wary gobbler coming to a call. Turkey densities in various part of the state have changed over the years, with some areas benefitting from a larger number of gobblers than others. Some areas suffered through documented, unexplained, population downturns. Many factors come into play when it comes to turkey numbers and hunter success, with the two closely intertwined.

Habitat is the primary factor influencing local turkey numbers because human beings can change the landscape for better or worse through urbanization and agricultural or forestry practices. The other main factor affecting turkey populations is weather. Poor spring and summer nesting and brood conditions due to cold and/or rainy weather can hurt turkey numbers.

- Click here to read more turkey forecasts from Game & Fish

The only factor that biologists can control is hunting pressure, which today means regulations skewing the harvest nearly 100 percent toward gobblers. Hunters take a few bearded hens because any bearded turkey is legal. However, the impact of taking a few hens is negligible. Going back to the six winter seasons of 2004-2009 in 10 mountain and northern piedmont counties, the few hens taken were so insignificant that they have no impact on recent years’ harvests. However, if hunters take too many toms during one hunting season and they are not replaced through recruitment, the following breeding seasons may find the forests and fields filled with fewer gobbling birds and the harvest declines. Now that maximum harvest levels appear to achieved, any increase in the current season length or bag limit could lead to reduced opportunities.

The state has such a diversity of habitats and weather patterns that one part of the state may experience a gobbler bumper crop while another may suffer a silent spring. Hunters should think of the state as a slice of Swiss cheese. Overall, it is a tasty treat, but it has holes of various sizes and shapes throughout. Turkey hunters who want the best chances of success should put their efforts in places where the gobblers are present in large numbers and not waste precious vacation days and weekends during only a month-long season in areas where gobblers are not as abundant.

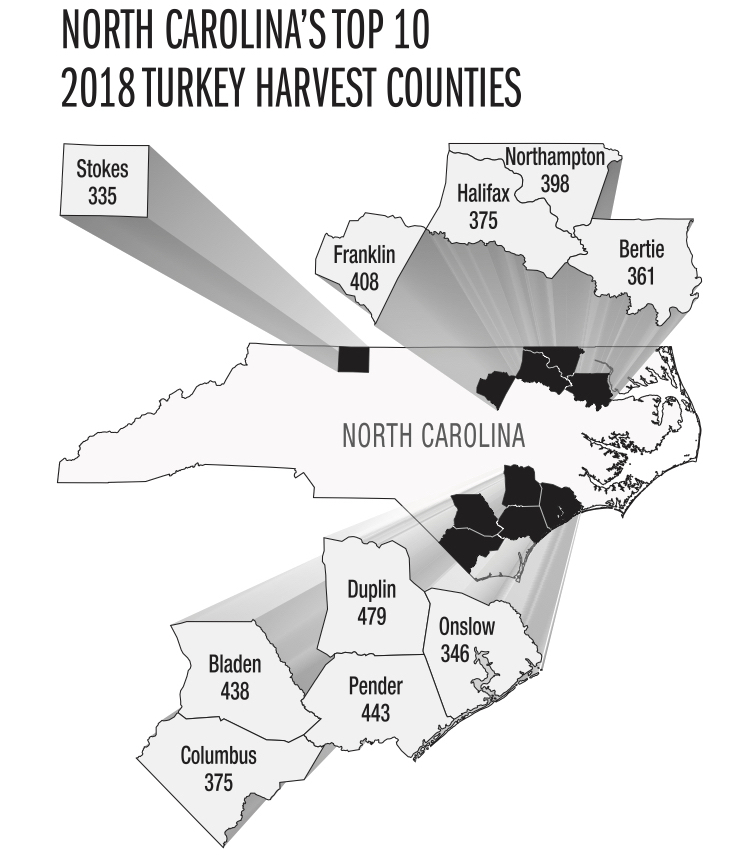

In 2018, the top five counties for gobbler harvest were Duplin (479); Rockingham (448); Pender (443); Bladen (438) and Franklin (408). Hunters should notice that three of these counties, Duplin, Bladen and Pender, are in the coastal plain and two counties, Rockingham and Franklin, are in the upper piedmont. The traditional counties for highest harvests were once in the mountains. However, many mountain counties have experienced persistent population and harvest declines.

Chris Kreh is the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission’s turkey biologist. He said that looking at the harvest figures on a county basis is probably not the way to find a hunting area despite the fact that the Commission reports harvests by county.

- Click here to subscribe to Game & Fish magazine

“If you take into consideration the size of the county, our top five turkey harvest counties are somewhat different,” Kreh said. “As with our deer harvest, which we also report according to harvest per square mile you have to take into consideration the size of the county. A small county will not have as many turkeys harvested as a county with a large landmass, if all of the other factors are the same.”

The top five counties for gobbler harvest per square mile were Franklin, Rockingham, Stokes, Northampton and Caswell, averaging 0.6 gobblers per square mile. These were the same counties with the highest gobbler harvest per square mile as during the 2017 season. The only different is their ranking order. Kreh also said that, while the harvest in Caswell has declined substantially over the years, it remains one of the top counties. In 2018, Caswell County produced 265 turkeys, including 32 from R. Wayne Bailey-Caswell Game Land.

“Turkeys are everywhere now,” he said. “We completed moving turkeys for the restoration project about 20 years ago. Now you have to look at the summer surveys to see how the population is doing in the different areas of the state. Ideally, we would like to see poults-per-hen numbers above 2.0. Our 2016 brood survey told us that we had the lowest reproduction since we have been doing the survey. The majority of the harvest is two-year-old gobblers, so when reproduction is down, it shows up as a decrease in gobbler harvest in the spring two years later. That is what we saw in 2018. In 2017, although it was a record harvest, the jake harvest was only 12 percent. The jake harvest is normally 16 percent, so that also was an indication of poor reproduction in 2016.”

In 2017, the number of poults per hen observed was 1.8 and the jake harvest increased to 15 percent. Those numbers are better than 2016, so they could indicate a better season in store for 2019.

Turkeys may be undergoing the New Ground Effect. Anytime a new animal is introduced, as was the case with turkey restoration, the population grows rapidly then suffers declines as the animal uses all available resources. The fact that reproduction (poults per hen) was higher when turkey populations were expanding than they have been in recent years is probably a result of this effect. Eventually, the population achieves equilibrium with its habitat. With the current turkey population relatively stable at 265,000 birds, the harvest may have reached its maximum potential as well.

Coyotes are probably experiencing this same New Ground Effect. As they have moved into turkey habitat, they have exploited all available resources, which can affect turkey reproduction because they eat eggs, poults and adult turkeys. Their numbers have will, or already have, achieved equilibrium with their habitat’s resources, which include prey species like turkeys.

In general, the 2018 harvest increased in the southeastern counties and declined in counties along the Virginia border. Hunters should take note of that when planning for 2019.

When deciding where to hunt, hunters should consider the harvest numbers for the area. However, as with a county, the size of a game land is also important. Bigger game lands produce more turkeys because they have more area if habitat is similar.

A large game land such as Nantahala with 528,782 acres spread across Cherokee, Clay, Graham, Jackson, Macon, Swain and Transylvania counties will likely produce a high gobbler harvest because of its enormous size. It yielded 248 turkeys in 2018.

Another factor is hunting pressure. Although hunting pressure is more difficult quantify, too much pressure on gobblers in an area can have an adverse impact on current season and future success. The Commission attenuates this effect by limiting turkey hunting on some of the smaller, high-use game lands by allowing turkey hunting only by those hunters who draw lottery permits. A dedicated turkey hunter would be well ahead of the game if they consistently applied for several permit hunts each year.

These limited permit hunts tend to fall into the smaller game land category, with their apparently low turkey harvests due primarily to their small sizes. A couple of exceptions include areas such as Jordan and Butner-Falls of the Neuse game lands, which are so close to large human population centers that opening them to all hunters would result in excessive hunting pressure along their lake shores. Their large acreages, Jordan with 40,937 acres in Chatham, Durham, Orange and Wake counties and Butner-Falls of the Neuse with 40,899 acres in Durham, Granville and Wake counties, are the primary reasons for their high turkey harvests. Large size is also the reason for high turkey harvests at the Upper and Lower Roanoke River Wetlands Game Lands throughout their various tracts along the Roanoke River that total 35,772 acres in Bertie, Halifax, Martin, and Northampton counties.

In the Coastal Region, the Commission’s game lands permit hunts and harvests were Pender 4 Tract of Holly Shelter, 8 (includes the entire game Holly Shelter Game Land); Singletary Tract and Turnbull Creek of Bladen Lakes State Forest, 16 (includes the entire Bladen Lakes Game Land); Suggs Mill Pond, 6; Goose Creek, 1; J. Morgan Futch, 0 (a new permit-only area); Lantern Acres, 1; Lower Roanoke River Wetlands, 22; Rocky Run, 2; Whitehall Plantation, 6 and White Oak River, 2.

In the Piedmont Region, the Commission’s game lands permit hunts and harvests were Nicholson Creek, 1; Butner-Falls of the Neuse, 23; Chatham, 6; Harris, 3; Jordan, 14; Rockfish Creek, 0; Sandhills, 25; Second Creek, 5; Tillery, 0; Upper Roanoke River Wetlands, 20.

In the Mountain Region, the Commission’s game lands permit hunts and harvests were DuPont State Forest, 2 and John’s River, 15.

Hunters should think about access and terrain before committing to a permit hunt or another game land hunt. Coastal and piedmont game lands are typically the easiest on the feet. The terrain in the mountains can be steep and rugged, making it difficult to approach a roosted gobbler. Some, like John’s River and Nantahala, have some water access to make hunting easier.

Another thing a hunter should understand about Commission game lands is that wildlife professionals manage these areas to produce good hunting for many game and non-game wildlife species. Food plots, prescribed fire, short timber harvest rotations and other landscape management practices produce turkeys at much higher densities than most private properties or even much of the national forest properties at Pisgah, Nantahala, Croatan and Uwharrie because the U.S. Forest Service’s top priority goals do not necessarily include providing hunting opportunities.

For every upside, there is a downside. Kreh pointed out some of the counties that were once turkey strongholds that are not producing as well as they were.

“Turkeys are not doing great everywhere in the state,” he said. “In the northwestern counties — Ashe, Alleghany, Person and Watauga — the harvests are much lower than the peak harvests for those counties in the early 2000s. For example, in Alleghany County, the harvest was 137 turkeys in 2018. Back in 2001, the harvest was 309. The decline could have been caused by a lot of things, but no one knows for sure what is happening.”

The Commission is doing an acoustic survey to see if the spring turkey season is biologically sound for optimal turkey numbers and hunter success. Current hunting season dates do not have sufficient science behind them to say whether they open too late or too early and run too short or long. To that end, biologists set up acoustic recording equipment in 2016, strategically locating the devices in areas where gobblers are not subject to hunting pressure such as state parks and large tracts of private property where the landowners do not allow hunting.

Once biologists have enough data they will be able to propose adjustments to the hunting season dates or bag limits. Biologists will report the results of the first four years in 2019 and could propose changes at that time. For 2019, the turkey hunting regulations remain unchanged.

In the past, hunters participating in the wild turkey summer survey received a postcard form in the mail. A recent change is that hunters can sign up to participate and report their observations via the Internet. To sign up, visit ncwildlife.org.