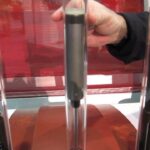

Uberti 1873 Cattleman II Brass Single-Action 9mm Revolver (Firearms News Photo)

The cartridgeutilizing single action revolver was the cutting edge technological advancement of the 19th century. The middle 19th century, to be a bit more precise, and it’s a versatile one, as well. As long as you didn’t go into magnum pressures or use something longer than a .45 Colt cartridge, you could (theoretically) build a single action in any pistol caliber. (In the 19th century, handguns were pistols. It wasn’t until the advent of the selfloading handgun designs that “pistol” and “revolver” diverged as descriptors.) I have a book around here someplace entitled; The 36 calibers of the Colt Single Action Army that lists the chambering that Colt did the originals in, in the history of its production up to World War II. Of the 36 cartridges, according to that author’s research (the book was published in 1965), Colt had not made a single SAA in 9mm Parabellum. That didn’t stop Colt, and the London office, from making SAA revolvers in various British calibers, and some samples and small orders in a slew of European cartridges.

The “oversight” of no 9mm was apparently corrected back in the early 1990s, when Colt made a small run for a European contract, and most of those got shipped overseas, making a Colt SAA in 9mm a rarity. I checked with our own James Tarr, and his Standard Catalog of Colt, and there’s no mention of any 9mm SAA to be found. I asked Tarr about that, and his reply was, “Never heard of an SAA in 9mm.”

Table of Contents

Uberti 1873 Cattleman II Brass Revolver

Well, there is one now, and it comes to us from Uberti. To give it its full title, it is the 1873 Cattleman II Brass revolver, and it is more than just a single action in an otherwiseoddtoacowboy caliber. OK, the exterior first. The frame is color casehardened. The barrel, cylinder and ejector rod housing are blued steel, and the triggerguard and grip strap are brass. This is a traditional combination and one I find quite appealing. The barrel length is 5.5 inches, what a lot of people refer to as an “Artillery” revolver. Now, personally, I prefer the looks of the 4.75inch barrel, and the handling and accuracy (longer sight radius) of the original, 7.5inch barrel, but the 5.5inch version is a nice compromise and apparently popular back in the days when the singleaction revolver was the exemplar of personal defense. Another upgrade is in the sights. Instead of the V notch rear, and the knife-edge front, the Uberti has a square rear notch in the frame and a squaretopped blade out front. That makes aiming a lot easier than the old ones.

The 1873 Cattleman II Brass has a one-piece wooden grip, so there is no grip screw in the wood, and this means there’s no screw to come loose and allow grips to fall off. (Yep, seen it happen, had to solve that problem a few times for customers as a gunsmith.) Oh, and the “brass” in the model name? That’s the triggerguard and grip. If you want steel, then you just go to the listing for Cattleman II Steel, and order there. However, with the steel model, you will only have your choice of .357 Magnum, .44-40 and .45 Colt.

SAA Operation

Where the Cattleman II (both the Brass and Steel models) really shines is in the firing mechanism. Okay, we all know that you load and carry holstered a traditional single action with just five rounds, right? Only those models with a transfer bar system can safely have the hammer down on a live round. To do so with a traditional one is simply asking for trouble, as the firing pin is resting directly on the primer of the sixth round. If anything hits the hammer, it can easily set off the primer, and that’s how more than one cowboy in the 19th century ended up with a limp. (At best a limp, you could die from that error in judgment.) The original process is simple. Open the loading gate and bring the hammer back to the cocking notch that frees the cylinder. (On the Cattleman II, the first notch) Load one round. Skip the next chamber, then load the next four. Cock the hammer and ease it down. Done properly, your hammer is now resting on an empty chamber.

That is not necessary with the Cattleman II. How? What Uberti did was give the Cattleman II a new firing pin system that isn’t a transfer bar, and thus it doesn’t look like one. What they have done is made the firing pin retractable. When the system is at rest, the firing pin cannot reach the primer. When you cock the action, the trigger pressure from the sear to the firing pin sear engages the firing pin, causing it to extend into firing length. When you press the trigger, the sear maintains that engagement, allowing the firing pin to strike the primer. If at full cock something causes the hammer to fall, but the trigger hasn’t been pulled, the sear does not maintain engagement with the firing pin. The firing pin retracts, and it thus cannot strike the primer. This is a clever system and is one that still retains the appearance of the traditional system. It does require a few extra, and some modified, parts, but hey, this is the 21st century after all, there are changes that are good, not bad.

A 9mm SAA Revolver?

And that brings me to the last part, the caliber. The 1873 Cattleman II Brass is chambered in 9mm Parabellum, and that may seem a bit odd. OK, it isn’t a traditional cowboy caliber, but then, most of those are longgone now, or seriously nonplayers in the modern world. The .45 Colt was the one most-often made, and that caliber is still going strong. The second was .44-40, and while it is still a capable cartridge, if you are looking for a reloading challenge, and one that might drive you to drink, the .4440 is high on the list. This is due to its thin and tapered case – crushing and ruining brass while seating bullets will happen in every reloading session. (In fact, only the .38-40 has a chance to top it, and it was fourth in the volume list of cartridges for the Colt SAA.) The thirdmost popular cartridge SAAs were chambered in was .3220. Yes, that’s right, a whole lot of cowboys felt right and properly armed, carrying a .32 around. In fact, looking through the 36 calibers book, I find that most of them were cartridges invented before, or long before, the 9mm Parabellum was developed.

There were 44 Colt SAAs made in .45 ACP. There were 625 made in .357 Magnum, up to 1940. The .38 Special? Only 27, and that cartridge is older than the 9mm. Lovers of the .44 Special know that it came along after the 9mm as well. So, why a 9mm, and wouldn’t there be problems? The cylinder is so long, right? Look around you the next time you are at your Local gun shop. How much shelf space is devoted to 9mm, and how much to.45 Colt? (Don’t even ask about .44-40, .3840 or .3220; you’ll get laughed at.) The 9mm is the default chambering in the modern world, and it’s the highestvolume pistol cartridge manufactured in the USA (and probably around the planet). If you make a handgun, and it isn’t chambered in 9mm, you are seriously missing the boat in the American market. Well, Uberti doesn’t want to miss the boat. But, the 9mm bullet has to jump a long way to get where it’s going, right? Maybe yes, maybe no, depending on what you think a long jump might be.

Yes, the 9mm is a lot shorter than a .45 Colt, but the smooth section forward of the chamber is simply a guide to the cylinder-gap jump and then into the forcing cone. Every bullet, regardless of the cartridge, has to navigate that passage. Colt managed it with the stubby .38 S&W in the SAA, which is, surprisingly, the same length as a 9mm Parabellum. Colt and S&W also managed this with the .38 S&W when making revolvers for the war effort in World War II, for shipment to our allies. I know for a fact those worked just fine. Of course, the proof is in the pudding, so that was something I was eager to find out.

The other facto is there’s no rim. Revolver rounds have to have rims, right? Again, no. As with the .45 ACP, 10mm, 40 and others, a pistol cartridge can headspace in a revolver by simply having a chamber the correct depth and letting the case mouth stop the cartridge. However, the 9mm has an additional advantage (or problem, depending on how you look at it) in that the case is tapered. So, basically, you have a cone dropping down into a cone-shaped space. It will stop even if there is no hard shelf at the front for the case mouth to bounce against. But, the Uberti Cattleman II Brass has a proper forward edge in the chamber, so you have both taper and shelf to ensure proper headspacing.

Now, if you had tried this, chambering an SAA in 9mm, back when I first started reloading 9mm ammo, you would have probably found it to be problematic. The variances of “acceptable” dimensions between ammo makers and firearms makers back then was just too great. Reloading dies were even worse. It was an obstacle that kept me from getting into reloading the 9mm Parabellum for a decade or so. Today, that’s not a problem. The 9mm ammo of today, in its most plain, commodity-like QC level, is match ammo compared to the best that could have been had back when I started. Today’s 9mm ammo is just made to a higher, more-consistent dimensional level today than in the “goode olde days.”

A couple of things I wanted to be sure of were some of the dimensions. So, I had to dig into the tools and fixtures chest to dig out my 9mm headspace gauges. I have not used them to check a pistol for a decade or so (I gave up after the umpteenth time of not finding a problem) to check the chambers. Also, the Colt SAA seems to be a bit more sensitive to the dimensions of the throats. These are the smooth, cylindrical sections in the chamber, forward of each chamber, cylinders that each bullet has to pass through on its way to the forcing cone. If the throats are too large, you get leading, too small, leading again. If they are not in agreement with each other, accuracy suffers. I wasn’t worried, just curious so I checked. Each chamber accepted a “Go” gauge, and refused a “NoGo” gauge, and the throats measured a consistent .3575 of an inch in diameter. That’s on the large side for a 9mm, by a thousandth or so, but that they are all the same was encouraging.

Disassembly

To clean the 1873 Cattleman II Brass, first unload. Bring the hammer back to the first click, and then flip open the loading gate. If there are fired cases, or loaded rounds, use the ejector rod to push each of them in turn out of the cylinder as each aligns with the loading gate. On the frame, ahead of the cylinder, is a spring-loaded plunger. Press this in (It only goes one way, in from the left side) and while holding it pressed into the frame, pull the centerpin out of the frame. With the centerpin out, you can now lift the cylinder sideways out of the frame, using the open loading gate as the clearance.

Scrub everything in the usual manner, then reassemble in the reverse order. Slide the cylinder in from the side, press and hold the retaining plunder, then press the centerpin down into the frame until it passes into the hole for it in the rear face of the frame. A detailed strip of the Cattleman II will require properly-fitting screwdrivers and the unscrewing of ten individual screws. You might need to do this once a year. Maybe.

But again, the proof is in the pudding, so that was something to be tested. And finally, the retracting hammer had to be tested. Since I didn’t want to damage the Cattleman II they so kindly loaned me, I couldn’t use a ballpeen hammer to test, so I got my plastic-headed mallet out of the Real Avid Toolkit. I put a primed case in the cylinder, under the hammer, and then I banged away on the hammer spur. Nope, no loud noises.

As is my usual process at the range, first I did the chrono testing, then the accuracy testing. OK, the felt recoil of your average 9mm cartridge, in a revolver that weighs 37 ounces empty, is just about nil. Now, the bore height over your hand is a lot. In fact, fellow gun writer Jim Tarr would no-doubt scoff at the height, as it is very large, compared to a self-loading pistol. However, there just isn’t enough recoil to roll the muzzle up very high on your hand, unless you are firing +P loads. The Uberti crafting of the SAA is strong enough for the .357 Magnum, (and you can even get a version of the Cattleman II Brass with both cylinders, for an extra $150) so I have no problems running 9mm+P ammo through it. Well, when I can find it. Speaking of cylinders, the Uberti, like the originals, has the cylinder numbered to the gun. If you order one with both cylinders, they both come numbered to the pistol, and that is one of those handwork details that they take care of in Brescia.

Now, running an SAA is easy. Well, easy once you get the hang of it. If you are shooting one-handed, then your firing hand thumb does the work. If you are shooting twohanded, then use your other thumb to cock the hammer, and you will have a lot more fun. Do not, and do not let anyone else, “fan” your SAA. Yes, it looks cool in the movies, but it is hard on the action, and will break things or throw it out of time. There are SAA pistol-smithing wizards who can rebuild a revolver to withstand fanning, but the cost of that kind of work likely exceeds the list price of the Cattleman II, so unless you are going to make a career of it and pay the price; don’t do it.

At the other end, using softy reloads, or the lowestpower, vanilla-plain 9mm ammo you can find, makes the Uberti 1873 Cattleman II a really fun gun. If you are looking to get a would-be shooter, new to the game, hooked on shooting, then the Cattleman II Brass would be a good starting point. Now, as a historical firearm not chambered in one of the cartridges that it could have been chambered in, in the 19th century, it isn’t historical. But it is a lot of fun, and it is a lot cheaper to shoot than one of the big bores, and it has as host of advantages over a 19th century sample. It has, as do all modern clones, improved steel, better dimensional consistency, and the great improvement of the retracting firing pin system. And, the Cattleman II Brass costs a lot less than a 21st century Colt, or a 19th century Colt. That cost difference buys a lot of lessexpensive ammo, as well. Get one, you won’t regret it.

Uberti 1873 Cattleman II Brass Specs

- Type: Hammer-fired, single-action revolver

- Caliber: 9m

- Capacity: 6 rds.

- Barrel: 5.5 in.

- Overall Length: 11 in.

- Weight: 37 oz.

- Finish: Blued steel, brass

- Sights: Notch rear, blade front

- Trigger: 3 lbs., 7 oz.

- MSRP: $599

- Manufacturer: Uberti

Patrick Sweeney is a life-long shooter, with more than half a century of trigger time, four decades of reloading, 25 years of competition (4 IPSC World Shoots, 50 USPSA Nationals, 500+ club matches, and 18 Pin Shoots, as well as Masters, Steel Challenge and Handgunner Shootoff entries). He spent two decades as a professional gunsmith, and two decades as the President of his gun club. A State-Certified law Enforcement Firearms Instructor, he is also a Court-recognized Expert Witness.

If you have any thoughts or comments on this article, we’d love to hear them. Email us at FirearmsNews@Outdoorsg.com.